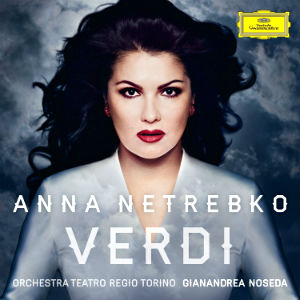

I’ve given up trying to figure out why divas gravitate to certain roles and not others. Years ago, Shirley Verrett told me with an entirely serious expression that her true role in Don Carlo was Elisabetta, “not the one with the eye patch.” For years, Anna Netrebko seemed destined to become the great Desdemona, Manon Lescaut and Madama Butterfly of her generation. But no: the roles do not “speak” to her and Netrebko has bypassed what seems like obvious repertoire in favor of some real head-turning operas, including Norma and Macbeth. Her new CD

of Verdi arias seems to be a bold, defiant, “in your face” statement about the direction she is taking with her career.

Netrebko comes out swinging with the program’s most controversial numbers, the three major scenes from Macbeth. They have clearly benefited from her application and hard work. In the liner notes, the soprano recalls:

“In the first session everything was actually there. I did scrupulously everything that was indicated in the score: the rests, the rhythm, the lines. And yet there was something missing.” [Five months later she re-recorded the scene.] “I took time over this role, brought it home with me, lived with it, let it sink in. And then suddenly everything really was there. The Lady was in me and in my voice. Suddenly everything automatically sounded more convincing without my having to make a special effort.”

The deep immersion Netrebko speaks of is immediately apparent: her spoken delivery of the letter has bite and is inflected with sinister hungriness. She communicates ferocious ambition throughout. But there is always a disparity between her dramatic intention and the basic sound of the voice: it’s just too wholesome.

Netrebko suffers from what I call “Freni syndrome,” or the inability to transcend the essential quality of her sound: the timbre communicates warmth, candor, “niceness.” It’s the reason I was never entirely convinced by Freni as Tosca (on record) or Fedora (on stage). The she-devil/tigress quality is elaborately constructed but does not sound entirely authentic. And so it is with Netrebko as Lady Macbeth. But no one can fault her for trying.

Vocally, she is limited too by her lack of facility in coloratura: the very first ascending run in the recitative is lead-footed, somewhat labored. And so it goes throughout. In addition, Netrebko has a weak, rather breathy chest register and has to navigate her way through low-lying passages with care. On the credit side, it is rare to hear such a glamorous sound in this music. There is almost a palpable sexiness in her singing that is in and of itself novel to hear. She negotiates the far-flying tessitura very well.

After the full-on “Princess Fire and Music” treatment of this scene, Netrebko is curiously blank in the opening section of “La luce langue” but becomes more engaged as she proceeds. She makes strong use of dynamics to score dramatic points. The Sleepwalking Scene includes the prelude but no Dama or Medico. Netrebko has a strong grasp dramatically on the material but she misses ultimate desperation and terror, settling for pathos and a sometimes self-pitying poutyness. The high D-flat is no “fil di voce” but neither is it embarrassing. It just sounds tense and uncomfortable.

The Giovanna d”Arco aria is the finest number on the album. There is no issue here regarding the fit of her voice with the character. Netrebko captures the dreamy, visionary nature of the heroine perfectly. The cavatina is wistful, lovely and deeply felt. This is gorgeous singing on every level and her glowing pianissimi are breathtaking here.

The Vespri items represent the low points of the disc. “Arrigo, ah parli a un core” starts out dramatically blank yet again. The two verses are not differentiated in any significant way and totally devoid of the chiaroscuro that made Scotto’s performance so special. The famous descending chromatic run is clean but nothing special and the ability to suspend time missing. I wonder if she “took time over this role, lived with it, let it sink in.” The Bolero is even more frustrating, due to the slow, plodding tempo she imposes on the music. The singing is heavy, not scintillating, despite a good trill. The producers were generous enough to supply the choral contributions but it is not enough to redeem the prosaic, pedestrian coloratura. There is no charm in the delivery, not even a hint of a smile.

With Don Carlo, we are handed blankness again. This could be a lovely role for her onstage but presently she lacks stature, the tragic dimension, the grand utterance we associate with Elisabetta. It’s as if she used up all her interpretative capital on Macbeth. She has not found her way into the skin of the character and her lack of a strong chest voice is most obvious here in phrases like “la pace del l’avel.”

The program concludes with the Act Four Trovatore scena and suddenly the soprano is dramatically alive and alert again, living Leonora’s dilemma vividly. The voice suits the music like a glove. The tone is gorgeous and her feeling for the legato line admirable. She sounds poised, secure, inside the music. In the Miserere, the two verses are well differentiated: the first all quivering anguish, the second fiery and angry. (Alas, Rolando Villazon‘s contributions as Manrico are off-putting; at this point, the tone is hopelessly squeezed and nasal, more suited to Mime or Herod.)

We get one verse of “Tu vedrai” and one becomes aware that Netrebko uses a slight scoop to reach the very highest notes. But it is a strong finish to an otherwise puzzling disc.

Gianandrea Noseda leads the forces of the Teatro Regio di Torino competently but he is clearly following his soprano’s lead and brings little point of view or accent to his work. The recording is state-of -the-art but the acoustic is unnatural. There is no sense of room or space around Netrebko’s voice, creating an almost clinical setting for the listener’s examination.

In summary, one is tantalized rather than fulfilled. The overall program would have benefited from the same care and detail that Netrebko lavished on the Macbeth numbers. Still, the Giovanna d’Arco and Trovatore selections are their own reward. “Live with it, let it sink in”—words for Netrebko the artist to live by.

Comments