The operas of Leos Janácek have been slowly gaining ground in the world’s theatres over the past fifty years. The composer toiled all his life in relative obscurity developing his unique brand of modernism. He wrote particularly well for the soprano voice and was attracted to complex stories that mirrored society’s role on the oppressed. The last twenty years of his life, when he had finally gained national recognition, were his most prolific. Even then, he was forced to edit his operas and alter his orchestrations for performance by the unenlightened management of the Prague Opera. Thanks to the compassionate musicology and impassioned conducting of the great Charles Mackerras we continue to enjoy important performances of these late masterworks in editions near to their original intention.

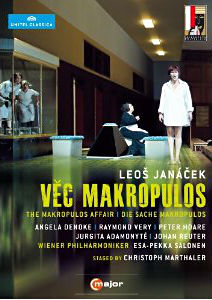

It took until last August for the Salzburg Festival to finally mount an opera by Janácek and it seems odd that they picked what could be considered his smallest work for one of the world’s largest stages. The Regie, as preserved on DVD, was entrusted to Christoph Marthaler who has been working on the world’s opera stages for the past 15 years. He’s known for his fascination with the mundane actions of daily life and using the nervous or calculated repetition of such for comic effect. The four men who the plot revolves around are treated especially poorly in this respect and, in the final scene, their collective reaction to the revelations of our heroine make them resemble a bunch of under-medicated epileptics.

Each act is established with its own silent prologue. Act I is preceded by a conversation in a glassed-in smoking area between two cleaning ladies that, essentially, gives away the entire plot. Thanks. Act III begins with the filing in, and then out, three times of the judges, jury and courtroom audience. By the way, there’s no judge, jury or courtroom audience called for in the libretto as nothing is set in a courtroom.

Meanwhile, Emilia Marty wanders the stage striking one meaningless pose after the next and rarely interacting with anyone directly. It’s essentially a Pilates workout in Czech. I don’t find anything wrong with abstract movement and design but I do take exception to completely ignoring the plot and not even bothering to tell the story. The bigger problem is who goes to the theater for an extra helping of the banal?

Production designer Anna Viebrock fills the Cinerama spaces of the Großes Festspielhaus with the aforementioned courtroom as the single set. Its high ceiling with second story windows looks outside at the sky. The height at the back of the stage is a detriment to any singer who wanders past the halfway mark upstage as their voices start to get lost in the space and lose focus. The courtroom is flanked on both sides by waiting areas that can only be an intentional salute to various decades of ugly civic architecture and furnishings. Two surtitle screens have been set up at either end of the stage and they’re a distraction on wide shots.

Angela Denoke has already presented her Emilia Marty in Milan and Paris and she does not disappoint, even in this foolish production. Her singing is nearly flawless and her voice rich at bottom and silvery at top in a role that is often bequeathed to a singing actress of a certain age and diminished assets. She looks good in her “Mondrian” cocktail dress and auburn bob in Act I, later changing to the men’s dress shirt of her most recent conquest. Heavy eye makeup indicates her “bad girl” status. I would very much like the opportunity to see her in a more traditional production as this one doesn’t really give her anything to work with as an actress.

The men in her life are really just presented as caricature like the nervous law clerk Vitek, well sung by Peter Hoare, who’s constantly drumming his fingers. Only Johan Rueter as Prus gets an opportunity to even start to develop a character but in the end he’s reduced to a shivering, frightened bunny like the rest. A small pleasure can be taken in seeing veteran Ryland Davies in his comic turn as the old paramour Hauk-Sendorf.

So, what could possible save this performance that seems to have both its dramatic hands tied behind its back Esa-Pekka Salonen’s conducting of the Wiener Philharmonic is the operatic equivalent of striking oil: the pit veritably gushes with the kaleidoscopic colors and spiky rhythms of Janácek’s magnificent score. Playing so precise and generous in its seductiveness that the stage fairly trembles from what’s exploding from the pit. It not only apologizes for this silly and pointless staging it makes it worth watching and nearly enjoyable.

Picture and sound are excellent and the video director, Hannes Rossacher, does an interesting camera trick in a very few spots where he slows the frames for emphasis, usually on Denoke in closeup.

I’m calling this an intriguing release but only for hardcore fans of this opera. You can always just turn off the monitor and enjoy the performance the old fashioned way and not be disappointed in the least.

Comments