Performed by the full forces of the Met Orchestra, Schubert’s brooding yet lyrical “Unfinished” Symphony was a rich and robust starter. In the first movement, the dead calm of the cello and bass invocation gave way to hauntingly subdued woodwind melodies and shocking, violent sforzando outbursts from the full orchestra. Here and in the alternately bucolic and nightmarish Andante con moto, the Met Orchestra showed masterful restraint and patience that rendered this familiar music fresh and surprising.

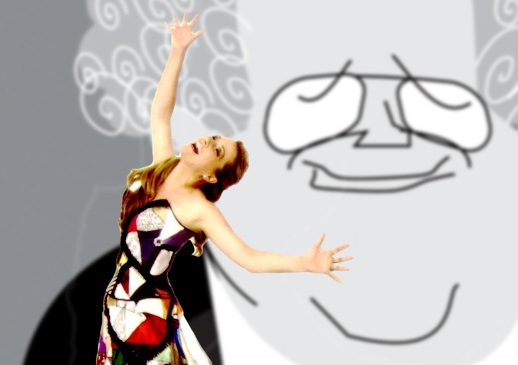

A big bouquet of Strauss’ songs followed, with the German soprano Diana Damrau. She was also an exercise in brand-identity marketing, appearing onstage in the same multicolored, paint-by-numbers dress worn on the cover of her recent album Coloraturas. In “Das Bächlein” and “Ich wollt’ ein Sträusslein binden” I had to close my eyes to know if the bright gem tones I heard were the product of visual suggestion or of sound. Strauss’ orchestrations are lush but colorful, matching Damrau’s lithe, golden soprano.

She gave a deeply affecting performance of “Allerseelen,” in which her sensitive reading of the text sank harmoniously into a lyricism of sublime poignancy, and she revealed proud and bittersweet exclamations of “Habe Dank!” in the one-minute masterpiece “Zueignung.” (After these songs of unusually touching poise, Damrau and Levine seemed as affected by the performance as their rapt audience, briefly pausing to catch their breaths before proceeding with the set.)

After this high point, “Morgen!” suffered, if only slightly. Levine was perhaps too accommodating of his singer, and let the tempo pull apart and lose direction. Poor concertmaster David Chen, who played the work’s famous violin solos with beautiful sensitivity but must have felt like a third wheel chasing their rubati.

In “Ständchen” Damrau took the text “um Keinen vom Schlummer zu wecken” (“so as not to wake anyone”) literally, singing as if to draw her public into a chamber-music intimacy, but lost some presence in cavernous Carnegie Hall. The trick worked better in the lighter-scored “Wiegenlied,” a creepily transcendental cradle song. Damrau’s Strauss-survey ended with the oddball “Amor,” a song of operatic, dazzling coloratura and metaphysical text-imagery, inhabiting the poem with a Zerbinetta-like wink and smile.

The real Zerbinetta (in Ariadne auf Naxos) is one of Damrau’s most famous roles, and one she sang at the Met in 2005, though not with Levine conducting. Nevertheless, the two demonstrated familiarity and camaraderie onstage in the extended bravura scene Grossmächtige Prinzessin! Damrau sang with cavalier confidence and vocal ease through its toughest passages. Though her take on the sly comedienne may betray a tinge of kitsch — for instance when her repeated vocal trills indicate a timid and precious giddiness — but she sells it convincingly, striking poses that melded statuesque classicism and a kind of modern grotesquerie.

Musically, she is of the highest order. If her upper register is not a gentle, creamy sound, neither is it shrill – the vibrant but rounded timbre suggests rich ceramic or silver. Damrau’s artful command of this music roused the matinee audience to an ovation demanding a repeat of the concluding rondo. With this concert already running long, an encore of this sort didn’t at first seem like a good idea. But Damrau took this opportunity to ham around, climbing onto Levine’s podium, motioning to him at the words “Ein Gott!,” planting an improvised kiss on the cheek, and offering other amusing shtick that would have been a shame to miss.

After more bravos for the soprano, the tutti forces of the Met Orchestra reconvened for Beethoven, giving a powerful and urgent, if just a tad messy, performance of his Fifth Symphony in C minor. Levine jettisoned the first movement repeat, and worked over the well-known with exciting tempo retouchings, as in the coda of the second movement, and Schumannesque crescendos that brought our long, Teutonic saga to a fiery and brilliant summation.

Comments