Evan Zimmerman/MetOpera

The Metropolitan Opera’s curtain rises for the 2025/26 Season on Mason Bates and Gene Scheer’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, its first outing in New York after premiering in Indiana last year. The source material is Michael Chabon’s 2000 novel that won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and no doubt the audience will be drawn by their familiarity with and affection for the book as much as they will to witness one of the contemporary operas General Director Peter Gelb and Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin have made a point of programming.

This championship includes a fair few operas adapted from well-known and regarded books. Nico Muhly and Nicholas Wright’s Marnie (2018, Met co-commission premiered 2017 at English National Opera), Kevin Putts and Greg Pierce’s The Hours (2022, world premiere), and Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer’s Moby Dick (2025, premiered 2010 at Dallas Opera) are some such productions within the past decade. Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek’s Lincoln in the Bardo (based on George Saunders’s Booker Prize-winning novel) is slated to premiere during the 2026/27 Season. As more and more openings on Broadway transform nostalgic films into pop-inflected musical theatre, this bookish trend at the Lincoln Center shows no sign of slowing.

Operas based on novels are no new phenomenon. Throughout history, great music dramas have been adapted from books that were acclaimed in their day and (mostly) still stand the test of time: Goethe’s Faust and Werther, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades, Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, and even Tolstoy’s War and Peace to name a few. Faust is, of course, technically adapted from a play, albeit a borderline unstageable one. But working from the likes of popular (and excellent) playwrights Shakespeare and Beaumarchais, and a text already designed to grab audience’s ears, makes for a slightly easier jump to opera. It is more of a challenge to change narration from words to music.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay is both an excellent novel and a deservedly popular one. Chabon’s sweeping narrative follows two Jewish cousins – one a Brooklynite, the other a Czech immigrant escaping the Holocaust – and their creation of anti-fascist comic book hero The Escapist. It captures both adventure and elegy in vivid characters and page-turning action. Many will be taking their seats already intimately familiar with the material.

Scheer is no stranger to adapting operas from prose fiction, counting Thérèse Raquin, An American Tragedy, Moby-Dick, Cold Mountain, and now Kavalier & Clay among his operas based on books. His process and ethos reveals the best potential of adaptation: taking a great book that has moved many people and finding a way to express its characters, ideas, and story in a new form. With the message in the medium, his approach is mirrored by other librettists who take words from page to stage.

For Kavalier & Clay, Bates came up with the idea and brought it to Gelb, who connected the two artists. Speaking to Scheer ahead of Kavalier & Clay’s premiere, he noted that he looks for “a simple story with large ramifications… that invites music in” when approaching a new project. “With opera, you’re trying to figure out how music can explore a story in an idiosyncratic way,” he adds. “It’s not an accident that a lot of the great opera stories are simple or focused. Then, like a stone thrown into a pond, the ripples can go out in all different directions and feel profound.”

The Hours, with a libretto by Greg Pierce based on Michael Cunningham’s 1998 novel, drew in fans not only of the three starring women – Joyce DiDonato, Renee Fleming, and Kelli O’Hara – but also of the Pulitzer Prize and PEN/Faulkner Award-winning book and the Oscar-winning 2002 film adaptation. The Met had commissioned Kevin Puts and found Greg Pierce based on his work on Fellow Travelers, a 2016 adaptation of Thomas Mallon’s 2007 novel, with composer Gregory Spears. While The Hours might have started out as just a job, the possibility of “simultaneous musical storytelling” drew Pierce in with the idea of the three women in three different times overlapping as innately “very operatic.”

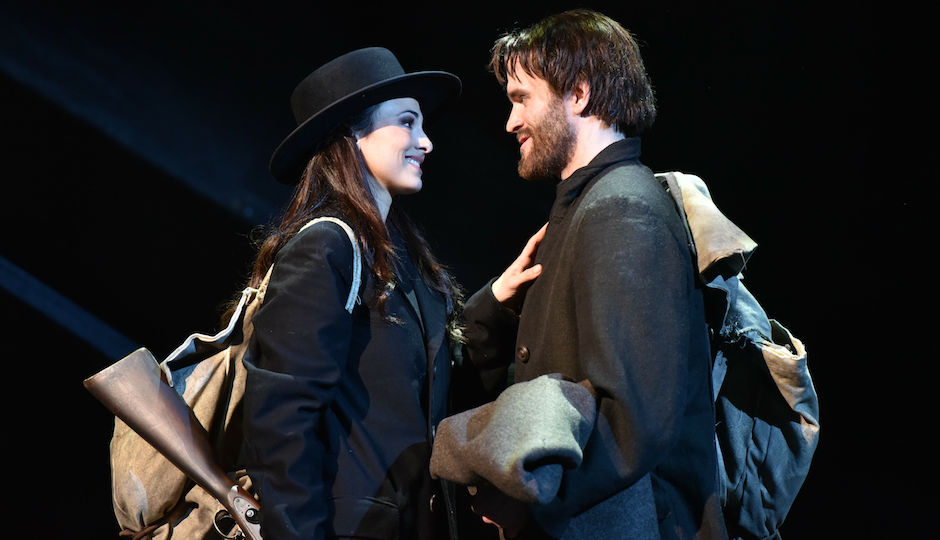

Jarrett Ott and Isabel Leonard in Cold Mountain at Opera Philadelphia in 2018, Kelly & Massa

When choosing an opera to adapt, name recognition is powerful for pulling audiences in, but it is never Scheer’s deciding factor; after all, there is a chance that the opera finds a fandom and life separate from its source material. “You’ll live with these projects for three years or more,” he notes, “and you have to believe at a fundamental level that music can illuminate the story in an interesting and different way. Whether famous or not, if you feel it can inspire you, you go with it.”

Popularity is not a concern of Pierce’s; the beloved novels have been a coincidence, not by design. His dream would be to adapt “a really obscure,” strange, or impenetrable novel and work with that challenge. “It’s really about stories,” he says. “Now that I’ve done a handful of things, I want to do stuff I haven’t seen before.” Even if an offer involves adapting a great, engaging book, for Spears it is less exciting if he’s “seen that sort of story in the world in some form.” With typical opera development lasting upwards of three years – The Hours was closer to four – excitement and enthusiasm are key.

Among the novel-based operas in the Met’s past decade, Marnie is an outlier in the sense that its fame comes largely from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1964 film than from Winston Graham’s pulpy novel. However, librettist Nicholas Wright noted in an interview conducted for this piece that the commissioning body had the rights to adapt Graham’s work alone: “I could use nothing that came uniquely from the film of Marnie, or from Jay Presson Allen’s screenplay,” he said. “I was not able to follow the imagery of the film and neither did I really want to, though I remain quite envious of Hitchcock’s evocative use of the color yellow.” But compared to Scheer and Pierce’s praiseworthy source materials, Wright is less complimentary about Hitchcock’s Marnie aside from its color scheme; he calls it “a work of Hitchcock’s senility.”

Scheer’s other opera at the Met in 2025 – Moby Dick, with Jake Heggie – took 15 years to make it there, arriving as this focus on championing contemporary opera was in full swing, but adapting Kavalier and Clay poses a different challenge; it may now be possible that more people have read Chabon’s novel than Melville’s, which presents its own challenges when it comes to condensing the original.“You can’t just take a novel and chop it up and put it to music,” he says. “When Michael wrote this beautiful book, he wrote it as a novel.” Scheer’s job with Bates was to get the novel down to what they considered the essential core, supported by musical storytelling.

A scene from The Hours, Evan Zimmerman/Met Opera

For Pierce, what makes a good book-to-opera adaptation varies depending on the different challenges of each project, but he also cites clarity. “People are singing and it’s harder to understand words, and if you’re reading subtitles, the process of digesting plot information is tougher than it is in a novel,” he says. “And technically, a line takes longer to sing than to say. If I were writing a play I could probably include more characters.”

Initial conversations were crucial for such condensations so that what remained was a satisfying whole. “Sometimes that means inventing little things here and there, which is part of the fun,” he says. He initially thought the novel the “perfect medium” for Cunningham’s story (“it’s a perfect novel,” he says), so the challenge became unlocking its “operatic experience.” Using the chorus helped collapse time and externalize inner conflicts. “They become the inner voices of all three women at different times,” he says. “They can be very quiet and subtle, or they can be really loud, doing battle with the main characters.”

Scheer stresses that the libretto is secondary – opera is a musical theatre form, after all – but the sung words must support the musical narrative. With Kavalier & Clay, a re-read revealed to him an adaptational framework that suggested the book had operatic promise. He and Bates created three different musical and visual worlds in Kavalier & Clay: Prague and the Holocaust (“a sort of black-and-white world Joe is leaving”), the “swinging” 1940s New York City (“immigrants and their energy and dreams of making a difference”), and the world of the comic book characters (with elements of electronic music). It is not just creating the worlds, though, but using them to reveal inner emotions and motivations via “musical solutions.” For Kavalier & Clay, in Gene’s mind, the goal is to use “the possibility of these three worlds smashing together” to communicate the book’s central theme: “how do you deal with loss?”

Writing believable dialogue is difficult without singing, and Scheer works with composers so that music becomes the exposition and narration rather than the characters’ info-dumping. “Music is the marrow of the matter,” he says about opera. “People do not go to the opera to read the libretto. This is not undervaluing the importance of a libretto, but a great libretto’s task is to call great music out of a composer.” Without this possibility for musical storytelling, Netflix would be a better medium.

Isabel Leonard in a scene from Marnie, Ken Howard/Met Opera

To Pierce, similarly, everything new about The Hours as a story comes from its music. “As a librettist, you’re constantly thinking how to be of service to the composer,” he says. “A lot of times it’s leaving space for the composer to do something in certain moments. I think composers really love to push a story forward, and dramatic music can help a story with very few words.” The wordless scene transitions created for the opera – such as when Clarissa first visits Richard and does not know what she will find – were especially creatively satisfying. “It’s giving music the opportunity to pull you in directions that sometimes prose can’t.”

The transformation and limitless possibilities of adaptation make it such a fertile well for opera writers. In The Hours, the overlapping narratives of the novel lend themselves well to staged music drama, with motifs and voices overlapping across time. Similarly, Muhly and Wright’s work is an adaptation for a more progressive time. But the book’s reputation had no impact on their choice of subject. “By the time I started work, Graham’s book was pretty well forgotten,” he says.

He is influenced by three factors: the story’s potential to be “effectively told in action, with a minimum of exposition and dialogue,” offer “good opportunities for female singers to shine,” and lastly, provide for “an exciting variety of singing voices.” In re-working Marnie’s thorniest elements into something distinct and dramatically coherent that gives the work a lease on life beyond the novel and inadvertently connected film, the work succeeds. With the novel told from Marnie’s unreliable perspective, the musical storytelling of opera can impressionistically get under her skin and in her mind in a way more literal storytelling formats – like film – cannot always.

Scheer hopes that Kavalier & Clay, with the immense love for its story and the energy he and Bates have put into it, is a great gateway opera for young people experiencing the art form for the first time. He also hopes the team have captured the experience of reading Kavalier & Clay in an entirely different medium. Moby-Dick reads far differently than Chabon’s novel, and therefore, to Scheer, the operas should play differently as well. Melville’s lengthy descriptions and monologues cannot be heard in the same way as Kavalier & Clay’s “energy and zip and sizzle.” He hopes the opera has all this fun, and thinks Bartlett Sher’s production rounds out what he and Bates created. “I hope it is appealing to a large audience,” he says. “I am excited about it, but who could possibly go to a Met premiere on opening night and not be a little nervous.”

A scene from Moby-Dick, Karen Almond

This whistle-stop tour leaves out several works and does not account for adaptations that have not yet appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, including Scheer’s Thérèse Raquin and Cold Mountain. Greg Pierce’s Fellow Travelers has had performances in regional US houses since its premiere at Cincinnati Opera and recently announced an upcoming multi-city tour. Interestingly, there is now a glossy television adaptation of Fellow Travelers, but unlike with Cold Mountain, The Hours, Marnie, or Scheer’s collaboration with Tobias Picker, An American Tragedy, opera got there first. While the film rights to Lincoln in the Bardo were acquired in 2017, Mazzoli and Vavrek’s opera will beat it to production next year unless Megan Mullaley and Nick Offerman pull off an unheard-of filmmaking feat. And Mazzoli and Vavrek’s most recent collaboration, The Listeners, became an opera before airing as a TV series last fall.

There are more cynical readings for the choice to adapt works based on relatively recent, famous novels, and the popular appeal of The Hours and Kavalier & Clay, despite their relative youth, feels like a hail Mary to draw people to the opera house, in the vein of prestige novels adapted to film every Oscars season. Moreover, these two books have thousands of fans, in addition to Pulitzers.

Yet there is still an overriding snobbishness around reading. Scholastic book fairs and Goodreads badges reward industrious effort, while turning to the Booker Prize list rather than Survivor for an evening’s entertainment is seen as more productive and virtuous. But people’s intelligence or morality should not be measured by what entertains them. Scheer touches on this when he discusses what draws him to a story he must live with for a three-year page-to-stage gestation. To him, Moby Dick and Kavalier & Clay are equally gripping, but some readers may adore Melville’s emotional potency and gripping yarn (with much digressing on whale sperm) while others find it inaccessible compared to alternate histories of New York and superheroes. Creative teams and commissioning bodies, many of which are new to opera development, might be missing a whole world of adaptation going for the award-winners and canonical classics. Yes, people love these novels, but they are not necessarily driving sales or landing in the charts. Populism still takes a backseat to the “right” kind of opera – but it does not have to.

Andrzej Filończyk in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Evan Zimmerman / Met Opera

As mentioned above, many great and enduring books became great and enduring operas. However, some of the world’s favorite operas have been adapted from books that lack the transcending, international popular appeal that their operatic adaptation has. Bizet’s Carmen is ubiquitous, but Mérimée’s novella appears less often on book shelves. The same goes for Dumas fils’s La dame aux camélias (La traviata) and Murger’s Scènes de la vie de bohème (La bohème). Voltaire’s Candide is more respected than enjoyed, but Bernstein’s Candide is a riotous, crowd-pleasing work (though not without its adaptive difficulties). Scott’s The Bride of Lammermoor is not among his best and his popularity outside Scotland and the American South overall has dramatically waned in the centuries after his death.

Of course, not all great books make great operas. Bernard Hermann and Lucille Fletcher’s Wuthering Heights took a great book and great creative team but did not prove very workable onstage. In the opposite scenario, sometimes the book is just bad: Abbé Prévost’s Histoire du Chevalier de Grieux, et de Manon Lescaut is structureless episodic drivel, a chore to get through on the page even as Massenet’s and Puccini’s versions both continue to work their charms on stage today. There seems to be no guarantee that prestigious novels automatically turn into beloved operas, or vice versa.

When interviewed by the New York Times ahead of the 2023/24 Season, Gelb and Nézet-Séguin said the focus was not on contemporary opera in general, but “the right contemporary opera.” In Gelb’s words, operas of many recent decades were “inaccessible to a broader public,” perhaps “works of great artistic merit, but by composers who were appealing more to the intellect than the heart of listeners.”

A scene from Fire Shut Up In My Bones, Marty Sohl/Met Opera

Gelb here namechecks composers Philip Glass and John Adams, notably not their librettists, but the idea of musical accessibility feels tied to the source material of Met-commissioned and Met-produced contemporary operas. With Nézet-Séguin adding that the issue is about connecting “with audiences and their emotions, and being more aware of reflecting the realities of today,” there seems to be a curation towards the esteemed and “worthy.” Similarities in seeking out starry, lauded, “important” material crop up across the Met’s other new and new-ish operas as well: Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones (which opened the Met’s 2021/22 Season) and Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally’s Dead Man Walking (which opened the Met’s 2023/24 Season) are based on acclaimed memoirs.

Where are today’s ladies of the camellias? While Madeleine Miller’s The Song of Achilles was adapted into a libretto by Jada Frazier as a student at the University of Richmond, a fully staged opera of this queer romantic tearjerker has all the makings of effective musical theatre. What if the impressionistic works of Sally Rooney were translated into music and sparse verse? On the less literary side, books by Colleen Hoover, Rebecca Yaros, and Sarah J Maas have topped charts with series of little literary merit but hundreds of thousands of readers. Should Peter Gelb spend more time on BookTok?

But another missed opportunity could lie in the obscure, using opera’s potential to turn obtuse, difficult, or under-explored stories into gripping musical drama – as Pierce wishes to do. Kaija Saariaho and Amin Maalouf’s L’Amour de loin takes inspiration from the work of 12th-century troubadour Jaufré Rudel; the Metropolitan Opera staged it in 2016, their first work by a woman composer since 1903. There is perhaps a higher commercial risk threshold to such adaptations that come lesser-known or lesser-loved, which has lead Pierce on “a quest to have librettists and composers sit down with opera companies and say, this is how we want to work, even if it’s unorthodox.” Embracing new modes of collaboration can provide opera companies new to opera development with “a real opportunity to figure out making opera.”

This examination is incomplete and unscientific, taken early in the Met’s renewed focus on new and “relevant” works. But the caché that prestige literary source materials lends to new operas often seems both to the detriment of less prestigious fiction that might find a new lease on life through opera and to the ambitions of the composers and librettists that endeavor to adapt those works. It is too early to tell which of these contemporary literary adaptations will continue to grace the operatic stage in the decades to come. Perhaps in the next century, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay will be mentioned in the same breath as La traviata, La bohème, and Manon Lescaut times two.