Nina Westervelt

“I’m not a music lover. I’m a musician,” says countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo as Maria Magdalena Galas. “I’m a musical instrument. I am music.”

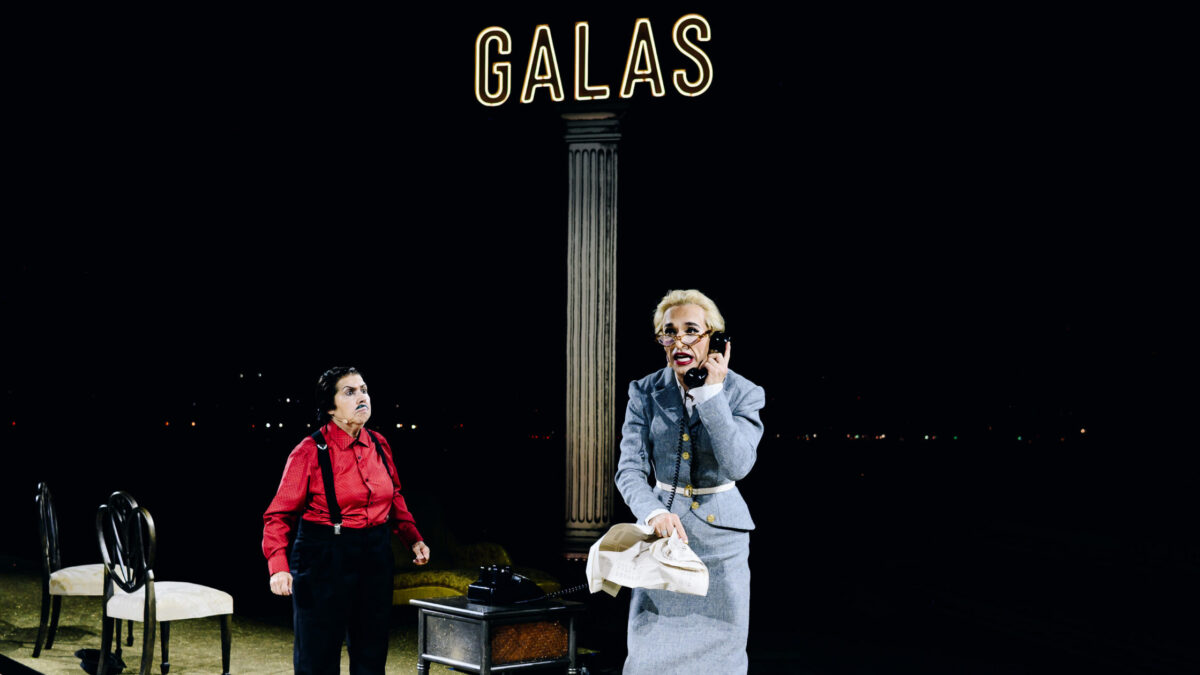

Charles Ludlam’s Galas, a fictionalized life of Maria Callas, didn’t originally have live vocals. (When Ludlam starred in its premiere, he simply lip synched to Callas’s recordings.) But at Little Island, Costanzo supplied them — all while walking surprisingly competently in heels. Sometimes a dress strap slipped off a shoulder to reveal an unshaven chest, even a glimpse of nipple.

“How?” I kept wondering to myself. “How is she so pretty?” In winged eyeliner, Costanzo does look quite a bit like Callas. But the similarity doesn’t really extend to his voice. Though Costanzo performed admirably, I am not running to hear him sing Tosca just yet.

Costanzo’s Galas, directed by Eric Ting, recalls last year’s “all-in-one-voice” Marriage of Figaro, which received mixed reviews. This time, the ensemble took up even more of the slack. Carmelita Tropicana, also in drag, played Galas’s husband Giovanni, while Samora la Perdida played an extremely cunty Pope.

Brilliantly, stupidly, anytime anyone said the words “La Scala,” they stuck out their tongue, as if at the doctor’s office.

Nina Westervelt

The maid Bruna, played by Mary Testa, was easily the funniest onstage. Her perfectly timed line, “Madam, your dog is dead,” was understated yet scene-stealing. She was a foil to Costanzo, whose acting often felt affectatious.

It wasn’t until the final scenes that Costanzo’s performance heated up. “I have no rivals, not until they act as I act, appear as I appear,” Galas declared. “I have many enemies, but no rivals.” I could hear echoes of criticisms aimed at Costanzo: “She can’t sing but she can erect a scandal.”

If “the voice is like the juice of a fruit, you squeeze it and throw the skin away,” then Costanzo’s countertenor is like citrus — sometimes too piquant, though in Galas mellowed out by the miking.

There actually wasn’t that much singing, however. Among the arias sung were “Casta diva” from Bellini’s Norma and “Ces lettres” from Massanet’s Werther. The latter was genuinely affecting. But any comparison to Callas is bound to fail.

Still, it makes sense that Costanzo might identify with Callas. Both artists have voices (and personas) that were, in many ways, self-made. And indeed, there was something draggy — even trans? — about Callas’s reinvention. (Note that Galas was full of weight-loss jokes.) Costanzo has compared his singing to drag. His voice doesn’t always align with his appearance.

Nina Westervelt

All of these personal resonances came to the fore when Costanzo removed his wig during the Madama Butterfly-style ending: “A knife is the perfect weapon for a female impersonator.”

My main criticism, however, has to do with something larger than Costanzo or even Galas. As I looked out past the stage onto the Hudson River, I couldn’t help but reflect on this time that we’re living in: What does it mean that a man in drag can land on the front page, while a transfeminine opera singer can barely get a gig? That a cis man with a high voice is celebrated, while a trans woman with a low voice is often sidelined?

Perhaps the idea is that someone like Costanzo produces a trickle-down effect. That if the public gets used to a man in a dress, they will eventually get used to trans people. But it doesn’t work this way.

The truth is that opera’s gender-expansive tradition is not always reflected in its institutions. And the popularity of Galas— with the relative lack of critical attention paid to works like Andrew Yee’s Trans Requiem or Kevin Carillo’s Figaro/Faggots — shows this.

For Charles Ludlam, who died of AIDS in 1987, the Theater of the Ridiculous was about resistance. It was about survival and representation. He wrote in his manifesto: “Test out a dangerous idea, a theme that threatens to destroy one’s whole value system. Treat the material in a madly farcical manner without losing the seriousness of theme.”

Ludlam saw cross-dressing as transformation. As acting of the highest order. It’s worth quoting him at length:

“Sexism motivates the prejudice against drag. A woman putting on pants has stepped up in the world. She’s going to business… A man who gets into a flimsy negligee or evening gown has become a concubine. He’s stepped down from his superior role… To defiantly … say women are worthwhile creatures, and to put my whole soul and being into creating this woman and to give her everything I have, including my emotions (remembering that the greatest taboo is to experience feminine emotions), and to take myself seriously in the face of ridicule was the highest statement… For me, to play the diva is to step out of being a mere director to become a goddess: a step up. It allows audience to experience the universality of emotion, rather than to believe that women are one species and men another, and that what one feels the other never does.”

I kept feeling, during Galas, as if a trans flag would fall down from the sky. “Gotcha!” Costanzo would shout. “This is what this has been about this whole time!” But alas, that didn’t happen. Instead, it’s all left to subtext. We are skirting, pardon the pun, around the issue.

Nina Westervelt

Yes, it takes courage for a man like Costanzo to wear a dress onstage. But it takes much more courage to live authentically as yourself, day after day. Epecially in the face of the hatred that is now commonplace. For transfeminine singers, it is not a costume. It is not a punchline.

In the pursuit of clowning, Costanzo’s Galas may have lost sight of “the seriousness of the theme.”

A few years ago, I might not have questioned a show like this. But even last year, in reviewing Costanzo’s Figaro, I noted how Costanzo has certain privileges as a gay man “deemed relatively unoffensive by most opera-going audiences” that allow him to make a show about the collapsing of gender.

I believe it would be offensive to Ludlam’s memory not to ask: What would it mean to take Galas truly into the present moment? To create something that is as revolutionary and dangerous as when it premiered? It would look — and sound — a lot different from what was at Little Island.