Jiyang Chen

When asked what has surprised him most about his career, American bass David Leigh insists that his entire career—from an imposing and smoking hot (more on that later) Commendatore at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in 2017 to his recent US breakout success as Hagen in Tanglewood’s 2024 presentation of Götterdämmerung Act III—has been a surprise. Although he’s now a rock-solid professional, carving out an international career as a dramatic bass, David hasn’t lost the somewhat goofy enjoyment of music and theater and learning and language he showed as an undergraduate at Yale, where he sang Purcell’s King Arthur, Lully’s music for Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, and Mozart’s Bastien und Bastienne in my early music collegium.

We laugh remembering his performance of the quack magician Colas’s aria “Diggi, daggi, schnurri, murri,” a fake incantation with no real melody from Bastien und Bastienne. The 12-year old Mozart would have loved David’s unselfconsciously thunderous and otherworldy sound. When I tease him about these and other roles he has probably let go of now that he’s in demand as Hagen, König Marke, and Gurnemanz, he laughs. “Basses are like German Shepherds—we never let anything go. Maybe we forget about it for a while. When you’re starting out, every teacher wants you to sing Figaro and Leporello, but the truth is that I got offered Verdi and Wagner parts before those. So, there’s a chunk of the repertoire that I kind of ‘let go of’ when I left school. But honestly, I suspect none of that is gone forever.”

Jiyang Chen

Leigh wasn’t even thinking about singing when he started out. At Yale he majored in composition, following in the footsteps of his father Mitch Leigh, composer of Man of La Mancha and other hit works for stage and television. “Our composition teacher told us that in the financial environment at the time, we shouldn’t apply to grad schools in composition as there was a scarcity of grants. When I told her I couldn’t apply as a pianist because my playing wasn’t that great, she said, ‘You sing, don’t you?’ Luckiest thing that ever happened! I didn’t particularly want to sing, but I wanted to be in New York, near my family, so I went to Mannes.”

He was an earnest student, dressed well, and paid attention. “It was the first time I heard big voices, and I loved it. I wanted to be around people like that. And they heard things in my voice. They would say ‘do more of this, and don’t worry about that.’ But it was all very weird, like in Harry Potter, finding out you’re a wizard. I think this is a bass experience,” he chuckles. “Once I was covering a guy who had been a chemistry professor in Iceland. People told him he had a good voice and five years later he was at the Met. Morris Robinson, similar story.”

After getting his degree from Mannes, Leigh returned to Yale, this time for a Masters degree in the opera department, where I remember him in as King René, the heroine’s father, in Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta. He had come a long way from the loud and pitch-insecure Cold Genius in Purcell’s King Arthur. As a voice teacher I am curious about what really happened at Mannes, what they did to tame his unruly voice and ignite his artistry. He credits Beth Roberts and Arthur Levy with this transformation, but I also know about David’s industrious side, and a work ethic drawn from both Yale and from his family.

Courtesy of David Leigh

After this he joined the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program at the Met, where the tall and lanky bass continued to tame his sound and perfected his German and Italian. Having spent much of his childhood in France, he speaks French easily, but admits that “singing in French is so hard! I spent my childhood in the south of France, so my tongue goes down my throat in two seconds!” He doesn’t sing much in French at the moment, but I wonder if he might he add Hoffmann’s villains to his repertoire? “I would love that, but I’m not positive that I can. I suppose if someone offered this to me, I’d try it out and I might say ‘Ah, this is surprisingly OK!’”

He’s also figured out how to tap into his imagination and relax into what he describes as a playful and creative state, especially when inhabiting older, more experienced characters. “I sing so many roles that describe experiences I haven’t had. If you’re a soprano singing Gilda you have probably experienced being a young woman in love and your parents don’t want you to be. Maybe your dad’s not a hunchback, but…” We dissolve in laughter. “And villains! I’m really lucky to do villains. I love it when it’s not mustache twirling.” But what about playing old characters at such a young age? “The first time I got made up to be really old, I looked into the mirror and burst into tears because I looked just like my father, who had recently passed away.”

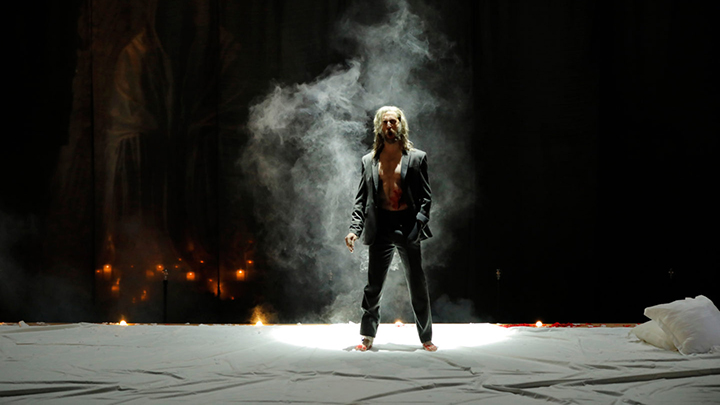

Pascal Victor / artcompress

He’s gotten used to playing fathers and has sung Mozart’s Commendatore several times, considering it a good role for a house debut (“better than Colline, for example, where you don’t really show enough to get asked back”). For the production I saw at Aix-en-Provence, he was a last-minute replacement in the 2017 festival. After the Commendatore’s murder, Leigh stalked the stage barefoot and bare-chested, haunting every scene in a trench coat and long, snaky wig. “At first they gave me a wig that, they said “sort of matches your…they didn’t say Jewish, but…I knew what they meant. Then they realized that it made me look too much like the festival director, and they didn’t want to seem to be making a twee joke.” So they switched the Jewfro for a long, curly wig. “I also had a gigantic scar on my chest and the makeup department built me a new scar every night. I thought, ‘Wow, they are so committed, this is awesome.’ But when we took the production to Luxembourg, there was one scar they used for the whole run. Why? It turns out that in France, they need to work a certain number of hours to get their benefits, so they took the time to build me a new scar every night!”

Adding to all this Commendatore haunting were clouds of smoke, which seemed to be coming from everywhere, including his pockets. “It was! And the smoke machine I had up my arm was burning me! But I was new, it was my European debut and I didn’t know how to handle this. One day one of the costumers said, ‘What’s up with the scars on your arm? Is this stigmata or something?’ Anyway, they quickly made a little leather cover to protect my arm.”

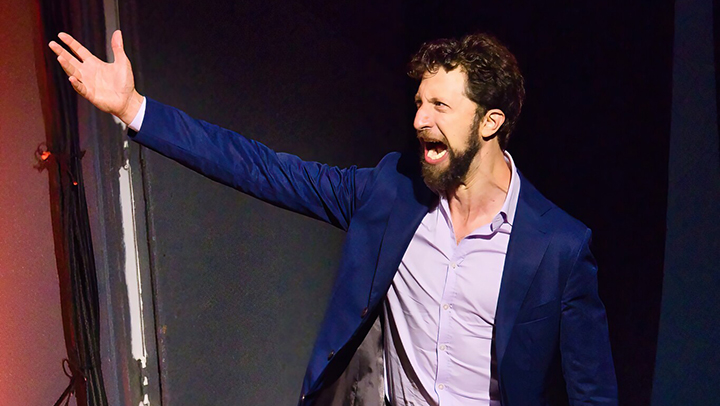

Hilary Scott

Early in his career, in another opera, David was struggling during the rehearsal period. “I kept losing my voice, I was asking for a day off, I was going back to my teachers to figure out what was going on, and why it was so tiring.” It turned out that the stage director had been demonstrating David’s character’s moves in a hunched-over, cramped way and David had tried too hard to please. He’s more confident about speaking up now and has even become comfortable being the youngster in the room. “When I was in school, I realized that what made me special was that my voice was darker and louder than everybody else. Now when I’m on stage with Wagner people I think, ‘oh, my voice is normal.’”

When we met up during rehearsals for the Tanglewood Götterdämmerung, he had been worried standing next to Christine Goerke. “It was so loud! But when I went out into the house, I realized it was regular Wagner singing.” While the score-bound tenor was struggling, Leigh filled every note in every rehearsal with solid and beautiful tone, and a variety of colors and declamation. He was the only cast member who moved confidently around the small playing area and used his height with deliberate menace. Much to my amusement, another former Yale early music singer, mezzo-soprano Annie Rosen, was singing Wellgunde with rich, dramatic sounds and alert diction. Maybe early music is not so pointless.

But vocal splendor is something else entirely, and all this fascinates me, as I don’t work with dramatic voices or heavy repertoire. Out of curiosity, I keep trying to imagine David in works that I do know well. What about Jesus in the St. Matthew or St. John Passion? He doesn’t want to say it, but he’s probably thinking “And who else could be in THAT cast?” But Jesus should stand apart. (When I sang my first St. Matthew, a Dutch pop singer was an appropriately charismatic Jesus.) I don’t imagine him in buffo roles, much as I love a big voice in a perky patter. What about paying homage to Sam Ramey’s spectacular appearance in the Met’s 1984 run of Handel’s Rinaldo? And there’s Monteverdi’s bass roles: both Nettuno in Il Ritorno d’Ulisse and Seneca in L’Incoronazione di Poppea could plausibly dominate the cast’s vocal sound.

Dreaming aside, every time he mentions Wagner, I think Verdi and even Rossini. His 2021 Filippo for Dallas Opera’s Don Carlo was cancelled, and I’m anxious to hear him in a non-German role. “I sang some bel canto when I was younger because I was a good student and people were sort of impressed. They would say, ‘What a cool instrument,’ but they wouldn’t hire me. They also said you need to wait five years to sing Wagner and all the other stuff and I said, OK. But actually I didn’t wait, and the minute I started singing Wagner people began hiring me.” When I press him further he actually claims to hate Rossini. I’m imagining him in even more Sam Ramey roles. “No one wants to hear me sing Rossini.” But when I ask about Maometto, he chuckles. “Well, I would sing Maometto.” Listen up, casting directors!

Leigh’s social media presence is modest and professional. “I don’t have a love-hate, rather a hate-hate relationship with Instagram, but it’s my job. I prefer Facebook’s long form, but that’s out. I have amazing managers who are very tolerant of my weakness as a self-promoter, and I think they—and the reality of my voice—insulate me from some of it. The challenge really falls on them: it’s hard to convince people that a relatively young person can sing Gurnemanz or Hagen, and no amount of Instagram followers solves that problem.”

With his background in composition Leigh admits, “I’m a huge believer in new music and I try to do a lot of new opera. I’ve done a couple that were actually written for me, but most of them have been projects I came into later. One of the first big breaks I got was doing the villain in Rufus Wainwright‘s Hadrian. The cast was unbelievable: Thomas Hampson, Karita Matilla, Ben Heppner, Ambur Braid. Rufus did a hybrid approach, where he wrote it first and then modified it as he got to know me and hear things in my voice.” He feels that composers are at a disadvantage in the creative process nowadays, because singers are not available for what Leigh calls “many hours of woodshedding, where composers can hear their music in our voices and get to know us as people. Obviously it would require a shift in the way we thing about compensation, but I think it’s part of the reason many new operas struggle to make it into the canon.”

Hopping between Europe and the US has made Leigh aware of the different economic models. “I’m from New York, where we stopped sustaining two major opera companies in 2013, and now we barely sustain one. But Berlin has three, and even tiny cities in Europe program bigger seasons than we program in Chicago. When you go see Carmen in Gelsenkirchen there’s another Carmen down the road and there’s going to be a Carmen next season. When people have that much opera to choose from, uniqueness becomes the coin of the realm, for better and also sometimes for worse. In America, when we have less to choose from, it becomes vital that each performance be the platonic ideal, so the standards become about delivering that ideal, and if it’s weird or different in any way people are disappointed.”

His favorite singers from the past are Tatiana Troyanos, Mario del Monaco, and Leonard Warren. He can’t possibly know how much I idolized Troyanos, so this choice must be genuine. “I know it’s a weird mix, but I would give a kidney to have heard Troyanos live. I’m an athletic person, so I’m a sucker for a real vocal athlete. Honestly I can’t deal with people who are great artists but don’t have great voices.” Nevertheless, Leigh is respectful and full of admiration for his colleagues. “I love opera. I don’t even need to sing it. I love standing on stage, but I also love getting comps to hear colleagues, or to hear a cool rehearsal. I sometimes think, ‘Wow, I got to stand next to so-and-so when they were really good.’”

Underneath this genuine awe and amazement at his success, it’s clear that Leigh continues to work hard in pursuit of musical and theatrical ideals and has always kept an upbeat attitude. During the intense Lindemann years he rewarded and energized himself by “walking in and out through the beautiful lobby, to remind myself what I was doing and why. Most of the time they were at the second intermission when I was leaving, but it kept me out of despair.” Other days and nights he was watching rehearsals and performances. He still goes to as many rehearsals and performances as possible, to support colleagues and to admire top artists. “Doing the Ring is super-fun. It’s immersive. When you sing Hagen you’re on stage for 6 hours, you never really leave the stage, it’s a long day, and it’s a transformational experience. But most performances are not like that. Marke is on stage for 20 minutes, but when I sing that I stand in the wings to hear everybody else.”

Hilary Scott

Coming up soon are his role and house debuts as Rocco in Fidelio in Washington, D.C. We argue over the merits of Beethoven’s opera, and I won’t reveal which of us loves it and which does not. “Rocco is a bigger role than I thought. He’s in every scene – he doesn’t shut up! It’s like Zuniga,” he laughs. “Zuniga sings more than Escamillo!” When we chatted, Leigh was about to leave to start rehearsals, which he’s looking forward to. “So often I play Pizarro types, real villains, but I love Rocco! It can go so many ways, and we’ll see how it’s played in Washington. It’s not exactly buffo, but if it’s played as funny, then I understand why he’s in every scene, because the opera can get very stuck, and needs some levity.” Leigh always studies the performance history of a role, and speaks easily of various musical and dramatic interpretations. “But often Rocco is not funny, he’s just charming and old.” He finds the role comfortable vocally, “but he has no place to breathe. He has pages without a rest and I want to ask Beethoven, ‘could you please speak the text to me in rhythm so I can hear where you breathe?’”

The serious and the light-hearted are easy companions in Leigh. “I feel Opera is entertainment but it’s also deep substance. I want to be doing only deep substance. I have no interest in the entertainment half at all. It’s milk duds to me.” He would rather turn entertainment into education. Intrigued by Google Glass, Leigh insists that it, or something similar, will make a comeback. “We need something better than supertitles. In Bohème, as the tenor is approaching the high C – people in the know are listening for this, but people reading the titles just see “the hope” – it’s absurd. I can imagine some kind of feed or commentary in real time during a performance. People could choose to follow different critics or singers, like Inside Baseball.”

Monika Rittershaus

He also loves live chats, and actually followed parterre’s chat during the 2023/24 Zurich Ring, in which he was singing Hagen. When he sees my shocked expression, he quips, “It didn’t bother me. I’m not famous enough for anyone in the parterre community to be shitting on me. I’ll know I’ve made it when the people on parterre start shitting on me.”

In addition to starting a family (“My infant son has just recently gotten used to how loud my voice is – he can be in the same room now when I practice, without crying!”), Leigh is still composing. More specifically he enjoys making arrangements of folk songs and other material. “People ask me all the time to do this for them, but I’m a big fan of making arrangements yourself.” In one of my Yale classes he wrote some very respectable canons. Yet he seems honestly and charmingly unaware that not everyone is capable of this. He is often scandalized by librettists, translators, and Italian coaches who don’t know about the metrics of Italian poetry, knowledge Leigh acquired as an undergraduate singing early music at Yale. And for the Mannes music theory placement exam, which got increasingly difficult, people were leaving after the first page, while David finished five hours later having analyzed 4-part counterpoint and written a fugue or two.

Leigh is aware of how intimidating his physical presence, intellectual understanding, and musical and linguistic sophistication are – he often asks himself “what can I do to be less challenging?” – yet colleagues refer to him as an absolute sweetheart. Having worked hard, he takes nothing for granted. “I remember when this detective novelist came to Yale to speak. He admitted that he hated writing but he loved hanging out with blue collar people and detectives and firemen, but that’s not a job. He said ‘writing is the price I pay for hanging out with those people.’ So for me, singing is the price I pay for getting to hear opera up close.”