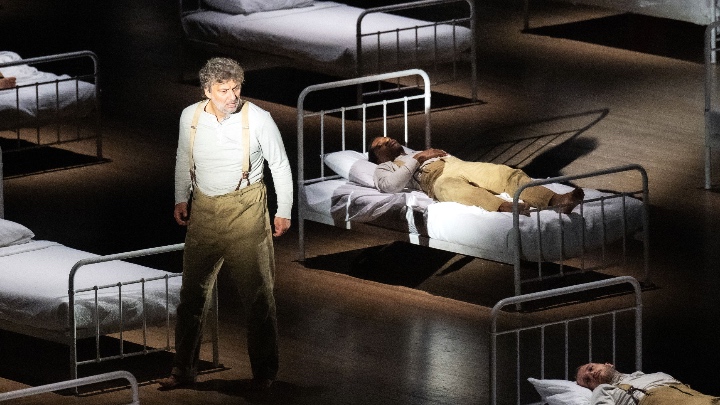

We entered the cavernous space of the drill hall to find it filled with rows of identical white iron beds; some were empty, made up crisply with taut corners, others were populated by restless sleepers, male forms that shuddered and fretted at intervals marked by metallic groans and light taps on the body of the piano, which sat at the center of the hospital floor. Nurses, identically dressed in turn-of-the-century uniforms moved silently up and down the columns, sweeping like wraiths along the floor.

This was not your typical lieder recital, in other words. Doppelgänger figures fourteen songs from Franz Schubert’s final cycle Schwanengesang as a series of reflections from a wounded solider, who wakes, dreams, and, perhaps, dies in the sterile purgatory of the hospital ward.

The cast consisted of large ensemble of soldiers, who crawled, slithered, and battled their way across the vast black surface of the drill hall, and a half dozen nurses—prim, erotic, terrifying—and finally, the stars of the evening, pianist Helmut Deutsch and tenor Jonas Kaufmann, who woke and began to sing, moving through Schwanengesang and haunting the ward.

Guth is not the first to stage art song in this way, even in recent New York history. Four years ago, Julia Bullock lent her voice to a semi-staged version of Dichterliebe in Bernard Foccroule’s Zauberland which placed the cycle in conversation with issues of forced migration and exile. But Doppelgänger successfully jolted Schwanengesang, and lieder, out of its typically staid surroundings and into a place of unease, terror, and longing. There is no plot here, just setting— though even that is somewhat ambiguous (it recalled most clearly the First World War)—and movement, but this is radical enough for a performance tradition that often begins and ends with singers trapped in the crooks of pianos.

Doppelgänger seems most inspired by its first song “Kreigers Ahnung,” (“Soldier’s Foreboding) and of course, it’s title track. “Ahnung,” foreboding, was certainly one of Guth’s primary registers, but throughout there was also memory, fantasy, and brief snippets of joy—or was it temporary insanity? “Der Doppelgänger,” is the peak of the Romantic horror—pain so trenchant that it makes you an unkind stranger, a ghost to yourself.

Guth’s strong command of space and sharp eye for striking tableaux made for a captivating evening, Images included nurses pacing between the beds, lit up by tracking rectangles of harsh cool light, beds stacked up into a makeshift barricade with men draped upon it, red confetti wafting from the high ceiling, like falling rose petals or bloody snow. While not always blazingly original, they were uniformly effective, and sometimes even stunning, as with the final number. Sommer Ulrickson’s movement direction was equally strong; one memorable moment showed the men lying on their backs, legs and arms reaching like dying bugs, while Urs Schönebaum’s sleek, effective light and projection design brought a distinctive stark, cruel beauty in contrast to the sensitive warmth of Schubert’s music.

Doppelgänger was at its most striking when it self-consciously engaged with lieder performance practice. Lieder is intimate, subtle, and individual: we sing it often in small spaces; it’s a “small” genre. Singers do not recede into characters in the same way they do in operas; we watch a version of their own identities. Doppelgänger, in many ways, was the antithesis to such qualities, staging instead their opposites. Kaufmann was one amongst an identically dressed crowd, looking small and very lonely. The size of drill hall—which takes up full city block—meant it was very difficult to see his face most of the time. His restless wandering meant no subtle quirk of eyebrow or corner of the mouth could translate. Even the vocal intimacy was mediated—Kaufmann was amplified by microphone.

Guth is clearly very aware of this element of his production, as was made clear after the final notes of the piano sonata had died way. Kaufmann, moving as if animated by an outside force, deposited himself in the crook of the piano for “Ihr Bild.” This he sang with focused fervor and brilliant control before collapsing, gut shot, to the ground. The nod to the traditional (and often terribly stuffy) performance practice felt well- earned at this point in the performance, making the metatextual thesis of the project clear while making it clear the ways Guth was recontextualizing and reinvigorating the tropes.

His staging of “Abschied,” which brief manic episode with Kaufmann’s popping out of bed in burst of cheer and frantic energy that broke with reality, was also smart in how it calls attention to a feature of this style: the incursion of sudden cheeriness in otherwise moody, dark song cycles. These interludes are often hard to make dramatic sense of for singers, but Guth’s reinterpretation turned that challenge into a strength.

Kaufmann was compelling throughout, delivering a very strong if never completely transcendent vocal performance. The use of amplification allowed him to indulge occasionally in his worse interpretive tendencies, namely, his propensity for pulling off his voice in pianissimo sections which renders these moments a bit too whispery and ghostly for my taste. But there were several standout interpretations from the tenor, especially the seductive “Ständchen” (my favorite of the set), “Ihr Bild” and the searing “Doppelgänger.” In these, Kaufmann showed a flexible mastery of his technique and of the genre.

Deutsch played with great vigor and tenderness, bringing out the balance of harmonic complexity and consummate melodic clarity that defines Schubert’s sound. This was especially apparent at the midpoint of the evening, where Deutsch played the second movement of Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-flat major in between the Rellstab and Heine portions of the cycle. This was nicely staged as a concert within Guth’s hospital, the ensemble watching spellbound or lost in thought, just like the audience. Such a pause, with Deustch’s sensitive playing, was a welcome moment of reflection in between the heightened drama. Also evident is the trust between Kaufmann and Deutsch, who have been long-time collaborators. Mathis Nitschke’s sound composition punctuated the pieces, returning always to the same restless foreboding that began the piece.

Doppelgänger’s best moments came when Guth leaned in to suggestion rather than clear depictions of war imagery; its worst moments were when Kaufmann and the ensemble over-acted Guth’s premise and veered into melodrama. At times, the weight of Guth’s interpretations proved more than individual lieder could bear —”Am Meer,” staged like a funeral march with Kaufmann’s bed as the coffin, was overblown and not particularly responsive to the text—resulting in moments that were dramatically motivated but unsatisfying as acts of exegesis.

By the time we got to the title lied, however, these interpretive misfires were forgotten. Impressively, Guth was able to cash the rather large dramatic check he wrote, delivering a positively spellbinding finale. Kaufman’s encounter with his double was meticulously directed and strikingly sung; the song itself is enough to raise the hairs on your arms, but after the succession of images that preceded it, combined with some very fine singing from Kaufmann, “Der Doppelgänger” was sublimely scary and impossible to look away from.

Photos: Monika Rittershaus, Courtesy of Park Avenue Armory