Soprano Julia Bullock paid tribute to pioneering Black composer Margaret Bonds.

I have written pretty extensively in these pages about the gems of the month, so please indulge me here with one more love letter to the last week of June 2023 in the city I call home.

On Pride Sunday, June 26, I traded my glitter shoes for black tie and headed to the beautiful Gunn Theater at Legion of Honor for a balls-to-the-wall, riotously hilarious Pocket Opera production of Jacques Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld (Orphée aux enfers). After all, the opera began with a Lady Whistledown’s doppelganger stating that:

“My rightful name is Public Opinion.

Although I play a thousand roles

And kings are under my dominion,

At home I’m simply called … The Polls“

Orpheus was Offenbach’s first full length opera—after presenting multiple one-act operettas in the previous years—following the relaxation of the Parisian theater licensing laws in 1858. With libretto by Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy, it was premiered as two-act opéra bouffon at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens on 21 October 1858 and then extensively revised and expanded in a four-act opéra féerie version 16 years later. Halévy subsequently would join forces with Henri Meilhac to produce libretti for Offenbach’s famous operettas (including 1864 La belle Hélène and 1867 La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein) and also Georges Bizet‘s evergreen Carmen.

Orpheus parodied the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—including making fun of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s sacrosanct Orfeo ed Euridice—and even further, arguably satirized the French manners and politics of that time by turning the gods into a scheming hypocritical bunch who was afraid of public opinions. Despite the controversies,

Orpheus was a great success since the premiere and since then it had been one of Offenbach’s most often performed operas till this day, particularly in Europe. The “Galop infernal”, however, turned into one of the world’s most recognizable tunes especially after the Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergère adopted it as the soundtrack for their can-can, and the tune is now forever associated with the high-kicking, skirt-raising dance!

httpvh://youtu.be/Wh5g75svRJ4

Pocket Opera, one of San Francisco’s beloved institutions, was started in 1953 when its Founder Donald Pippin began giving a weekly concert series first at the hungry i and then at The Old Spaghetti Factory in North Beach. The concerts grew up to include operas and proved to be very popular. In 1977, the opera world took over completely and Pocket Opera was incorporated as a nonprofit organization, with Pippin singlehandedly run the whole show as its Artistic Director—from planning, casting, translating, conducting, rehearsing and even narrating the plot—till his retirement in 2019, succeeded by Nicolas A. Garcia. Sadly, Pippin passed away in his sleep on July 27, 2021 and Bay Area lost its beloved impresario.

The cornerstone of a Pocket Opera presentation is Pippin’s own sparklingly elegant English-language translation of the libretto, and over the years he had collected around 90 English-version operas of various styles and languages, from Bach to Bellini, from Verdi to Wagner (Das Liebesverbot, handsomely performed last season), from Mozart to Mussorgsky. Interestingly, Pippin refused to translate any Handel operas (and Pocket Opera had introduced about half of Handel’s 40 operas to Bay Area) and presented them in concert-style in Italian instead.

The fascinating collection of Pippin’s interviews with Caroline C. Crawford titled A Pocketful of Wry: An Impresario’s Life in San Francisco and the History of the Pocket Opera, 1950s-2001 gives a detailed account about his translation process (and his love of Handel’s operas), most importantly about how he avoided literal translations and instead took the energy and flow of the opera and developed his own texts to match them.

Pippin clearly loved Offenbach’s music, and he translated 13 of his works (the most from a single composer), including the famous operettas and The Tales of Hoffmann. Pocket Opera, too, made it a custom to present at least one Offenbach annually. The full texts of Pippin’s version of the Orpheus in the Underworld can be accessed here.

Personally, I always have a soft spot for Pocket Opera, as the first opera I’ve ever seen in San Francisco (and correspondingly, in USA) was their production of Gaetano Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, and every year I try to attend at least one production of theirs. I had a fond memory of watching Pippin leading Orpheus in the Underworld at Napa Valley Opera House a year before the 2014 earthquake that destroyed a portion of the building.

From the beginning, I truly admire the natural phrasing of Pippin’s translations, and I highly regard his body of work among the best English-language opera translations. Especially for his Offenbach’s translations, I daresay his words and rhymes came close to match the wittiness and brilliance of W. S. Gilbert’s (for Arthur Sullivan)!

The Sunday performance was acutely directed by Bethanie Baeyen, working closely with stage manager Chase Kupperberg, with costumes provided by Joy Graham Korst and props by Daniel Yelen. Collectively they presented the story in a light and irreverent manner, a laugh-out-loud nonstop action throughout. They made full use of the few props, and ultimately, filled the tiny stage of Gunn Theater with so much joy and laughter worthy of the source. Superbly, they didn’t skimp on the irony, particularly when the entitled gods strike to “rebel against the bullying … Arise! Arise” and, almost prophetically, request more beer!

httpvh://youtu.be/I-3GznRMwzI

Musically, the Sunday show was a revelation, as Frank Johnson coaxed the tiny Pocket Philharmonic into a lively and spirited reading of the score interspersed with his own excellent piano playing. I got teary-eyed when Johnson, after playing the famous Carl Binder-arranged Overture, in a homage to Pippin took the centerstage to narrate the story about to unfold!

Pocket Opera assembled a fine group of Bay Area talents to fill the 14 principal roles of the operetta, and on the whole, they performed the show as a tight ensemble piece as they sang, danced, acted, laughed and yes, did the can-can! As evident from the trailer above, they were clearly having fun doing it as well.

Decked in short shorts and a tank top, Amy Foote dazzled with her no holds barred portrayal of bored and horny Eurydice, easily navigating Eurydice’s many coloratura passages with bravado. As the title role, the debuting Nathanael Fleming personified loopy Orpheus—not a son of Apollo as in classical myth but merely a rustic music teacher—with big booming voice, and Orpheus followed Marcelle Dronkers’ half-motherly, half-Whistledown Public Opinion like sheep, because, in his own words “bound to Public Opinion, I’m a prisoner without bail.” Andrew Metzger brought bright clear sound and sexy bod to the scheming Pluto, and Erich Buchholz rounded the principals with a hypocritically authoritative Jupiter; his fly duet with Foote brought down the house!

The rest of the cast was similarly performed in high octane, from Sonia Gariaeff’s jealous Juno, Phoebe Chee’s rebellious Minerva, Abigail Bush’s lovelorn Diana, Daphne Touchais’ alluring Venus and Alicia Hurtado’s hyperactive Cupid in wheeled shoes. Caleb Alexander showed off his considerably patter skills in his Mercury’s aria, while Andrew Fellows and Sam Rubin were sufficiently stern and drunk as Mars and Bacchus respectively. Sidney Ragland completed the cast with double roles of the plaintive John Styx in Act 2 and a member of the heavenly squad in first act.

On Friday June 30, I went back to Davies Symphony Hall for the final concert of San Francisco Symphony 2022-23 Season featuring one of San Francisco Symphony Collaborative Partners, Julia Bullock. Collaborative Partners are a group of artists from multiple backgrounds and disciplines invited by San Francisco Symphony and its Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen to explore and develop new ideas in their areas of expertise and, eventually, transform the Symphony.

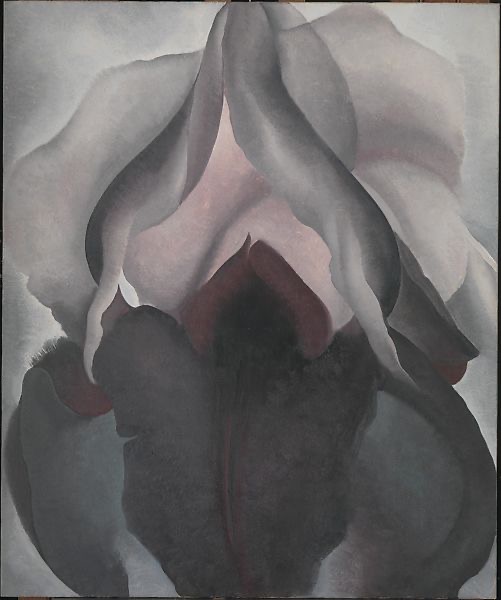

This series of concerts was a night of many firsts for the Symphony, beginning with Reena Esmail (born 1983)’s orchestral composition Black Iris. The powerful 10-min piece was commissioned by Chicago Sinfonietta (and premiered there in 2018), and Esmail revised and reorchestrated it for these performances. Originally titled #metoo, it chronicled Esmail’s own experience of sexual abuse and that of other survivors and, later she decided to rename the piece after Georgia O’Keeffe’s well-known painting, stating that “the light petals on the top, and the dark petals beneath—the image was so resonant with the experience about which this work was written.”

Esmail prefaced Friday’s concert with a short description of the structure of the piece, she even sang the Hindustani melody (she is of Indian origin) that served as a leitmotif. Like the picture above, the work was basically divided into two, a propulsive—and yes, masculine even—section using the orchestra’s full-force that stopped in the middle, almost as if it entered a black hole, followed by a dark and striving second part that gradually rose to climax at the end, with—the piece’s coup de théâtre—a wordless chorus by the female members of the orchestra as a kind of the divider in between.

Salonen excelled in bringing the highly emotional composition to life, detailing Esmail’s vast orchestration (the percussion section was pretty varied) and leading the score with great dignity. Although the blink-and-you-miss-it wordless chorus might not be exactly obvious (especially for audience in the back of the hall), nevertheless he demonstrated the “struggle” from the second part and the final “triumph” vividly, fully conveying Esmail’s message loud and clear.

Salonen brought similar qualities to a higher scale with the almost hour-long piece that formed the second half of the concert, Maurice Ravel’s 1912 masterpiece, Daphnis et Chloé. The symphonie chorégraphique was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev for his Ballets Russes, and it premiered as a ballet at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris on 8 June 1912, choreographed by Michael Fokine and the orchestra conducted by Pierre Monteux, SF Symphony’s fifth Music Director who also conducted the SF premiere of the score in 1947. Correspondingly, Monteux’s 1959 recording with the London Symphony is still my reference point for this great beauty!

Fokine’s ballet scenario was adapted from a pastoral romance by the Greek writer Longus, describing the quest for love for orphans Daphnis and Chloé against all odds. The story—which involved bandits, pirates, nymphs and even the god Pan—resembled the modern-day action-adventure romantic comedy (think Romancing the Stone or last year’s The Lost City) and Ravel’s score was extraordinarily lush and passionate and highly evocative of the story, aided by significant contributions throughout from the wordless chorus.

Salonen conjured images of the story like a magician (the program notes gave details for each scene) with his vivid rendering of the score; the flirtation scenes were sensual and amorous, the chase scenes thrilling and intense, and the Pan scenes sufficiently haunting and terrifying. He chose a well-paced tempo that moved the action forward, and in his hands the orchestra sounded exceptionally clean and alive. The SF Symphony Chorus, led by guest director Joshua Habermann, blended nicely with the Orchestra to create a united front, weaving harmonies after harmonies as if they were an instrumental section of the Orchestra. The bacchanale Finale was extraordinarily thrilling!

As June is designated to be African-American Music Appreciation Month, it was only fitting that Bullock chose to highlight the works of Margaret Bonds (1913—1972), one of the pioneers among Black performers and composers in the US. Bullock picked two Bond songs—both settings of her frequent collaborator Langston Hughes’ poems—“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” and “Winter Moon” and performed them sandwiched between three George Gershwin songs, “Somebody from Somewhere” from Delicious, the evergreen “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess, and “Soon”.

Performing with a mic throughout, Bullock showed a great respect and admiration to Bonds, particularly in the riveting “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”, long regarded of Hughes’ signature poem, where she imbued each word with a deep sense of contemplation, particularly on the repeated line “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” In “Somebody from Somewhere”, Bullock—who admitted being influenced by jazz legend Ella Fitzgerald—clearly demonstrated her influence while showcasing her glamorous low notes.

Throughout the set, she employed a wide range of color and expressions to set the moods, playing close attention to the texts she was singing. The best, at least to me however, came as the encore with her stirring rendition of the Leonard Bernstein’s perennial “Somewhere” from West Side Story, a paean of hope that was desperately needed for our time.

On Saturday July 1, I went back to War Memorial Opera House for the final performance of Madama Butterfly that closed the Centennial Season. I wrote in detail about the production in my previous review, but this production marked the official “debut” of Mexican-American tenor Moisés Salazar—a first year Adler Fellow with San Francisco Opera—as B.F. Pinkerton (The quotation marks were because Salazar covered the indisposed Michael Fabiano for June 27 show also).

What a glorious debut it was! Salazar brought a rich, sonorous bright sound to the role, with an ease of delivery, glorious phrasing, and commendable breath control. He made a sympathetic Pinkerton (almost too sympathetic, perhaps), portraying the character more as a lonely person in foreign land rather than the usual pompous jerk.

The long love duet with Karah Son as Butterfly that ended Act 1 was passionate and profound, truly depicting two young people in love (especially after Butterfly being renounced by her family), and their voices blended gorgeously. Salazar’s “Addio, fiorito asil” in Act 3 was achingly heartbreaking, the pain was clearly reflected in the voice. His intensity seemed to radiate throughout the stage, and on Saturday everybody seemed to be operating in higher plane, resulting in a truly powerful show.

Seen for the second time, I garnered deeper understanding of Amon Miyamoto’s staging and further appreciation for his nuanced reinterpretation of the story, helped by the extremely detailed pre-show lecture by SF Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock himself. Shilvock even shared a few interesting tidbits, including the fact it was Suzuki that was in the silent scenes, and most interestingly, that the ending was changed from the Tokyo/Dresden presentation to the current tableau (Dad/Son reconciliation, rather than Pinkerton/Butterly one in death).

So there you go, a recollection of one fine week in San Francisco, exploring everything from social commentary, female empowerment, Black composer appreciation, to love and forgiveness. As Jeanette MacDonald sang in the beginning, “San Francisco, open your Golden Gate” and continue to be the place for excellence!