The opera was an immediate success at its opening in Venice, and continued to be widely performed through the 19th century, then became something of a rare item in the early 20th.

Ernani, a former nobleman turned bandit after his father’s murder by the then King of Spain, passionately loves Elvira, a noblewoman sent as a ward to the castle of the elderly Don Ruy Gomez de Silva, who also has designs on making her his wife.

This “love quadrangle” is completed by the arrival at Silva’s of Don Carlo, King of Spain, who intends to have Elvira as well, by force if necessary. Elvira is steadfast in her love for Ernani, even pulling a knife to free herself from the King’s clutches; her bravery and single-minded desire to fight for what she wants in a man’s world makes her one of the more powerful female characters in all of Verdi.

The opera explores themes of love vs. duty, and whether one’s personal honor must be served at all costs. When Ernani, trying to escape the King, promises Silva that if he helps him, he will kill himself when he hears Silva blow a hunting horn, we know it’s all downhill from there.

This idea strains credulity, as does the changing of Carlo from villain to hero in the course of a single scene. Then, when Elvira and Ernani are united and joyful at last, we hear (of course) the hunting horn. And, straining credulity even farther, Ernani elects to stab himself in fulfillment of his promise despite Elvira’s pleas. The price of honor indeed!

But the singing in this production is so spectacularly good that the plot flaws seem unimportant. Tenor Russell Thomas used his clarion voice to wonderful effect as Ernani, singing with power and precision, yet able to sing with a palpable sweetness in his scenes with Elvira.

Soprano Tamara Wilson, seeming slightly underpowered in her opening of “Ernani, involami…” quickly warmed in the cabaletta and produced gorgeous silvery tone through the rest of the opera, her voice soaring over the orchestra and chorus in ensembles and singing at all times with sensitivity and warmth. Her acting is also fine, especially in her moments of ferocity in defending herself and her lover.

Quinn Kelsey was brilliant as Don Carlo, his dark baritone ringing out with rounded warmth throughout, whether snarling in his rage or sweetly wooing Elvira. He also acted the role very well, making convincing his Act Three transition from tyrant calling for the noblemen’s heads to newly found grace as he forgives the traitors and allows Elvira and Ernani to be together. It’s a grounded, mature performance of a very difficult role.

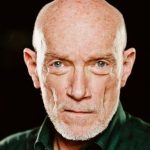

We were also lucky to have the formidable bass-baritone of Christian Van Horn as Silva, pouring out the dark beauties of his voice, caressing the words with wonderful phrasing. He also acted with style and grace, making his character’s convoluted notions of honor and hospitality seem real. What a pleasure to hear four such fine voices in all the principal roles!

Lyric Music Director Enrique Mazzola (after leading a slow and turgid “Star-Spangled Banner” to open the proceedings) leads a spirited, rousing rendition of the rich score and the Lyric Opera Orchestra responds with superb playing. Mazzola brilliantly alternated between the light and dark elements of the score and moves it with snowballing intensity.

The set and costume designs by Scott Marr added immensely to the success of the production. The rather minimal but stylish sets clarified location and action well, and his costumes are beautiful, colorful, and perfect in period design. Duane Schuler’s lighting, which I usually find too dark, worked well here with fine choices of brightness and color.

I am always amazed by the stunning precision and exact diction of the Lyric Opera Chorus under Michael Black, and it was very much in evidence here. The first scene with the chorus of male bandits was a model of clarity and group singing.

Stage director Louisa Muller kept the action moving well and told the story admirably, though the staging was somewhat static and mostly turn-front-and-sing-out. She added several special touches to her direction, some of which worked well, and others, not so much.

I think it was a big mistake to stage the murder of Ernani’s father during the overture, and then to have an actor wandering about as, I assume, his father’s ghost throughout. I didn’t figure out until Act Three who this (uncredited) actor was supposed to be, and he proved a distraction.

On the other hand, the very last moment of the opera was excellently done. As the curtain fell, Elvira holds the knife that killed Ernani and stares at Silva. We were left not knowing—will she kill herself? Will she kill Silva? It reminded me, frankly, of the last episode of The Sopranos!

On the whole, it was a very satisfying evening of Verdi sung by four stars at the height of their powers.

Photos by Cory Weaver