Cameron Kelsall: Indeed, it’s a complicated and multifaceted story, one that is told distinctively in each of its major adaptations. A viewer with an interest in film history can also chart the evolutions—both positive and negative—of the industry by watching each in quick succession. Although just ten years separate the 1929 version, the first full-length talkie produced at the legendary Astoria studios, and the more familiar Wyler-Davis collaboration, a world of change happened—most notably the implementation of the Hays code, which imposed a set of quasi-catholic standards on movie morality. Some of the more frank elements that director Jean de Limur highlights in his treatment, as well as its fairly forthright handling of racial (and racist) tropes, are muted by Wyler. The 1956 television adaptation featuring McKenna—an entry into the Producers’ Showcase series, when live theatrical productions were the growing rage in the early days of the medium—falls somewhere in the middle, awkwardly applying the rather gruff aesthetics of teleplays to melodrama. Although each version is entertaining—sometimes supremely so—thinking about them is often more stimulating.

DF: Exactly. As you say, just threading our way through the texts is an editorial adventure, and each change is significant in terms of how we understand the story. One example among many: the “other woman” in the story is, in two of the versions, as well as the original play, given no name (she’s simply called “Chinese Woman” in the dramatis personae), but in the Wyler-Davis film, she’s “legitimized” as the wife (not the mistress), and actually called “Mrs. Hammond.”CK: She is also pointedly described as “Eurasian,” likely due to the code’s anti-miscegenation provisions.

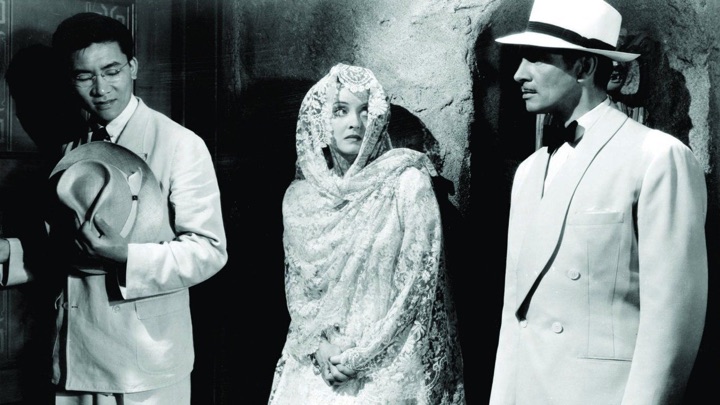

DF: As played by Gale Sondergaard, what could be an embarrassing example of yellowface casting has its own sense of grandeur. But I’m digressing, and we haven’t yet even commented on the stars! Cameron, why don’t you start with Bette Davis?

CK: Davis commands the screen from her first entrance, wielding a gun to kill her faithless lover with a chilling sense of ease. She already possesses the hard-as-nails quality that somewhat calcifies in later performances, but here she also conveys an appropriate sympathy that makes Leslie Crosbie a fascinating, and troubling, figure. You can’t help being drawn to her, even as you know she’s a liar, a murderer and a fairly heartless operator. I’ve heard admirers for years describe this as their favorite Davis performance, and it’s easy to see why; she brings her entire range to the role, and you can’t take your eyes off her.

DF: I’m dating myself for sure here, but looking at her here, I instantly thought of Kim Carnes’ song, “Bette Davis Eyes.” Her gaze is so utterly compelling and arresting—and as an actor, Davis is smart enough to know here when not to overdo it. Much of her performance has a sense of casual ease, which underscores the assumption that her status as a British plantation owner’s wife is its own protection. She’s imperious without seeming cruel… she simply expects it. The luxe-ness of her life might look almost comical in lesser hands—I counted not one but three fabulous Orry-Kelly outfits that she wears just in the few minutes between shooting and going to jail—but somehow Davis pulls it off, so it’s never merely camp. It’s also fascinating to watch her scenes with Sondergaard, whose own towering presence is real competition.

CK: Davis further benefits from a strong scene partner in James Stephenson, playing her lawyer and family friend Howard Joyce. Their scenes together are charged with chemistry, in which Leslie’s femininity and good breeding erode Joyce’s sense of moral duty, causing him to break the law and risk his professional reputation to save her face. Both Davis and Stephenson were Oscar-nominated for their roles, and their performances are in fact far superior to those of the actual winners (Ginger Rogers for Kitty Foyle and Walter Brennan for The Westerner, respectively.) Sadly, Stephenson died a year after the film’s release; his performance here serves as a testament to a talent lost in his prime.

DF: Another exceptional performance here is by Herbert Marshall, in the rather thankless role of Robert, the cheated-on husband. Marshall’s own personal story is quite extraordinary—a World War I hero, he lost a leg in battle and for the remainder of his life, worked with amputees. Curiously, he had played the lover in the first film of the The Letter—with Eagels—but here, his rather soft and sad quality is ideally sympathetic. A year later, he would famously be paired again with Davis in The Little Foxes, where a similar chemistry between them is equally gripping.

CK: Victor Sen Yung is also superb as Ong Chi Seng, Joyce’s office clerk, although the adaptation handles the fraught relationships between white Britons and native-born Singaporeans with far less nuance than its predecessor. (Max Steiner’s score, full of familiar Orientalist soundscapes, underscores this, as do scenes that feature offensively stereotypical depictions of opium smoking and jade hawking.) The notable actress Freida Inescort makes much of a rather throwaway role as Joyce’s wife.

DF: I agree about both these performances as highlights, and also about the very problematic nature of the character of Ong, who will be seen in two other versions that each give a somewhat different sense of perspective (not necessarily better, but different). In a follow-up piece, we’ll discuss the other versions in more depth. But before leaving Wyler’s film behind, I hope we can say something about its absolutely sensational visual appeal. Emphasizing the exotic other-ness of “the Orient” in Western culture is notably problematic, but what Wyler—along with cinematographer Tony Gaudio, art director Carl Jules Weyl, and the rest of the design team—do with every frame of this film is nothing short of magical. You will want to live in every single tableau.

CK: This version of The Letter is decidedly not a critique of colonialism—perhaps intentionally, or perhaps because it couldn’t be—so it makes sense to luxuriously present the lifestyles of the gentry in Singapore. To me, the lush settings underscore the darkness of the story, adding to the many ways it endures as a complex and disturbing proto-noir. Even encumbered by censorship, Davis and company still deliver.

DF: Cameron, I know we intended to look at all three of these versions of The Letter together, but there’s so much to it that I think we need to break it up. Shall we continue next time with Eagels and McKenna?

CK: Indeed. And we also plan to cover more ground in Bette Davis’ long, looooooong career—feel free to drop any suggestions or requests in the comments.