When he was a schoolboy his grandmother grasped his deep love of music and encouraged him with frequent visits to the opera. Later he was consumed with classic Yiddish theater and Jewish mythology. In 1991 he founded the Gilgul Theater Company (Gilgul: the transmigration of souls) whose 1991 production of the The Dybuk astonished critics and audiences alike.

His work at Gilgul culminated in a life-altering visit to Auschwitz, which in turn informed his seminal 1993 production of The Golem, music by Larry Sitsky, for Opera Australia. In preparation, he toured Eastern Europe, “trudging around with a guidebook in hand…very taken by the central European aesthetic and also by the magic of the decay and neglect. It was an aesthetic, and a way of life, so foreign to what he’d experienced as a nice little Jewish boy in Melbourne that it was a rude awakening for him.”

This immersion in Jewish culture led to the mysticism of Kabbalah, “which literally means ‘to receive’… according to which the Jewish concept of paradise is the unveiling of all knowledge.”

Moses und Aron was a natural project for Kosky, a monumental work wrestling with the paradox of believing in a nameless, unknowable God. Schoenberg had rejected his Judaism as young man and then publicly re-embraced it in the face of the Nazi onslaught.

In Moses und Aron Schoenberg’s struggle with the essence of his own Jewishness is the cosmic glue that bonds Kosky’s to Schoenberg’s vision. Brecht, Yiddish theater, Weimar/Berlin culture, high and low, vaudeville, and silent movies, burst through the monumental symmetry of Schonberg’s kaleidoscopic twelve-tone structures. Everything echoes something else. Everything refers to something else.

Before the show begins a projected snippet from Waiting for Godot establishes the tone.

Estragon: We always find something to convince ourselves that we exist, don’t we, Didi?

Vladimir: Yes. We are magicians.

Waiting for Godot itself arguably has the flavor of Yiddish theater as mediated through vaudeville shtick for gentile audiences and uses the physical tropes, the deadpan, slapstick, and absurdist humor. Kosky has spent a career transforming these tropes into something tragic and profound and personal.

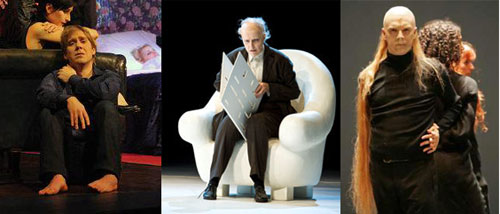

The ambiguous setting is vaguely ominous, circles of light in the ceiling and bare tiers vaguely suggest the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Moses’s entrance is a thudding roll out of a carpet. Robert Hayward, in top hat and tux, meets the daunting directorial and musical challenges with style and fiery conviction.

Nothing is played simply for laughs; everything totters at the brink between the ridiculous and the sublime. His own shoes bursting into flame are the burning bush he tries to elude but which follow him, conjuring the archetypal alienation of the wandering Jew, here at the beginning of his wanderings, unable to elude the impossible burden his God is placing on his shoulders.

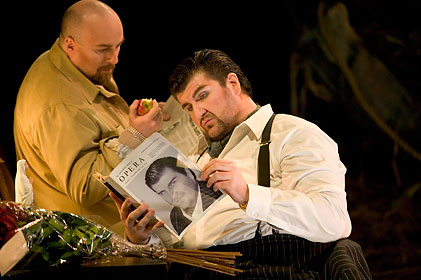

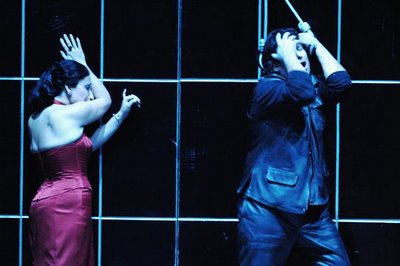

Spiritual suffering is rendered in a language of physical anguish, Brechtian grimaces, silent movie turns, and a vocabulary of gestures for the chorus. Aron, John Daszak, arrives, his partner and accomplice, Laurel to his Hardy, his florid vocal lines in stark contrast to Moses’s sprechstimme. A polished showman, he opens with magic tricks and a huckster’s confidence before failing spectacularly.

The chorus brilliantly meets both Kosky’s physical demands and Schoenberg’s musical demands, now as the voice of God, now as a commenting Greek chorus, now as terrified refuges, now as mad orgiastic dancers, now as Israelites furious at their new God’s opacity.

Conductor Vladimir Jurowski also seems to draw on his Jewishness to illuminate the contradictions of this unique score, composed in the twelve-tone technique Schoenberg invented, yet bursting at the seams with dance hall tunes and silent movie music à la Mahler and Weill.

Jurowski has said “[Mahler’s] music wouldn’t have been the same had he not been part of the diaspora culture… The folk songs and dances, the military calls, the irony, all these distinctively Mahlerian sounds are drawn from his experiences in the shtetl culture of Jihava, in Bohemia, where he grew up.” Jurowski mines Schonberg’s score while Kosky digs deep into the anguish of facing a God who demands exclusive and absolute obedience but refuses to name himself and whose essence cannot be grasped by human reason.

Bravi to Kosky and Jurowsky for this revelatory performance of a work more debated than performed and more diffidently respected than appreciated or understood. Bravi tutti to the cast, orchestra, and chorus of Komische Oper for setting the stage on fire.

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

-

Topics: barrie kosky

Latest on Parterre

Merry Widow | Finger Lakes, NY | July 25-28

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments