In fact, Oropesa’s Manon was consistently upstaged, not only by the opera’s leading man, but by an excellent cast of supporting singers who effortlessly carried the production in spite of Oropesa’s shortcomings.

This was no small feat: Manon is supposed to have an inescapable charm, a magnetism that causes men to flock to her like moths to a flame. She is the locus around which all events and characters revolve. If the character of Manon remained the centerpiece of last night’s performance, it was because Oropesa’s castmates placed her there.

It was not so much that Oropesa’s Manon was bad per se. Oropesa had an elegant sense of line and a bracing clarity to her voice. If her top was a little temperamental at times, and her lower register a tad pinched, it did not derail an otherwise pleasant performance.

However, it is not enough for Manon to be merely pleasant: Massenet’s heroine must be utterly resplendent – or at least dazzling enough to command the show. And Oropesa’s Manon frequently failed sparkle, lacked the energy and color essential to the role.

Oropesa started out promisingly, coyly channeling Maria von Trapp in a playful rendition of “Je suis encor tout étourdie” (although her bouts of coloratura laughter seemed insincere at best). However, her lifeless performance of “Adieu, notre petite table”, while sitting in her more comfortable middle range, inspired little sympathy for the conflicted Manon.

Although Oropesa redeemed herself somewhat with a flightier, spritelier Act III gavotte, her “N’est-ce plus ma main?” was so drab that the line “is not my voice […] like a caress?” felt slightly ironic.

In general, Oropesa was more animated in the duets and ensembles, her performance reinvigorated by the stronger performances of her co-stars. Thus, the Act III love duet and the Act V death scene saw Oropesa in best form, the presence of Fabiano injecting her sound with a new vitality.

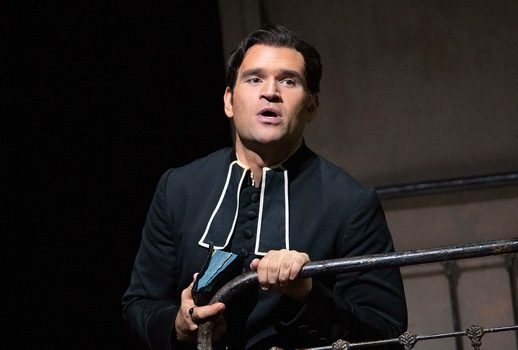

Indeed, Fabiano was like a breath of fresh air almost every time he graced the stage. His des Grieux had a bright, Italianate luster – a rich, full-bodied sound with a subtle spinto twang. His lower and middle registers had a gutsy, organ-like quality while his top notes soared with breadth and control, often swamping Oropesa’s considerably smaller sound.

While it is difficult to pick out highlights from such a consistently effulgent performance, Fabiano’s Act I wooing of Manon was simply outstanding, with Fabiano exploring the sweeter corners of his voice (I had always thought it odd that Manon falls for des Grieux so quickly – I was left with no such demur after Fabiano’s performance).

Fabiano’s Act II “Ah! Fuyez, douce image” had plenty of blaze and bluster, and felt refreshingly uninhibited after his particularly terse duet with des Grieux père (Kwangchul Youn, suitably staunch). Fabiano turned the temperature up a couple of notches in his Act III love duet with Oropesa, which saw her tear open Fabiano’s surplice in a fit of unbridled passion.

And, of course, his final duet with the dying Manon was simply glorious. Fabiano’s tender, floating pianissimo had me in fits of sobbing well before the curtain came down.

Artur Rucinski’s Lescaut balanced warmth and gravel in a performance that captured both the lightness and the pluckiness of the character. His voice was all silvery sheen in his Act I “Regardez-moi bien dans les yeux”, evoking a rarely tender sense of cousinly affection, although it lacked a bit of definition in the Act’s ensemble scenes.

Carlo Bosi, in the role of Guillot de Morfontaine, had everything one could possibly want in a comprimario character tenor: a twangy, slightly acerbic vocal quality with a gnashing clarity of articulation and a gauche, slightly foppish physicality.

His opening folly with the three glamorous actresses (Jacqueline Echols, Laura Krumm, and Maya Lahyani) and the innkeeper (Paul Corona) was flush with Belle-Époque decadence; however, it was in his more villainous turn later in the opera that we glimpsed the full breadth of Bosi’s dramatic talents as Guillot turns from jealous fool to crazed avenger.

French opera of the nineteenth century can rise or fall on the strength of its couleur locale, and Echols, Krumm, Lahyani, Corona, and, of course, the Metropolitan Opera Chorus truly rose to the occasion on Tuesday evening, providing a scintillating backdrop for the opera’s action. The three actresses, in particular, were exceptional in their ensemble work, especially in their rollicking Act IV quartet with Manon.

Maurizio Benini’s conducting was rather slapdash, and the orchestra and chorus often seemed sluggish in responding to his baton. There were some issues with woodwind intonation earlier in the opera, which smoothed out over the course of the performance.

The performance lost all momentum in the Act III ballet which, in addition to being dramatically extraneous, was played all too mechanically and treated to a banal choreography by Lionel Hoche.

Laurent Pelly’s 2012 production typified the circumspect aesthetic of the Met’s recent productions – part period piece, part cubist fever dream – as if someone had staged a performance of Hello, Dolly! in an I. M. Pei building (a shout out, here, to Pelly’s costume designs, which placed Oropesa in a dress of Eliza-Doolittle-at-the-Ascot-Races proportions in the third act).

For the most part, however, Pelly’s production was not particularly ostentatious, blending into the background and staying well out of the singers’ way. The production presented few new insights into Massenet’s opera and, while some of Pelly’s stylized movements added an edgy rhythm to the Act III choruses, the production was far from compelling.

Indeed, it was Fabiano, and his coterie of supporting characters, that brought out the glamour and the passion of Massenet’s opera.

Photos: Marty Sohl / Met Opera