Twenty-two years later, the new Coventry Cathedral saw the premiere of Britten’s War Requiem. It’s hard to imagine now the frisson of that first performance, in front of an audience many of whom will have remembered or even fought in World War One. The frisson that came, too, from its being sung by Fischer-Dieskau the Wehrmacht conscript and Pears the conscientious objector, and with the Cold War preventing the scheduled soprano from appearing.

Now we are significantly further from that premiere than it was from the Great War, and humanity’s desire to fight itself is as fervent as ever. Daniel Kramer’s staged production of the Requiem, which opened last night at ENO, sets itself a huge task in attempting to reflect the enormity of conflict, and despite some wonderful moments, it doesn’t quite succeed.

The headline news for this production is probably the stage design debut of the Turner Prize winning visual artist Wolfgang Tillmans, and his contribution encapsulates the successes and failures of this production. The aesthetic of the production, built around photograph and video projections, is stunning. It all looks staggeringly beautiful.

An image of the old, ruined Coventry Cathedral goes into closer and closer focus until the stage is dominated by a grassy stone. We pull in further, until the sprigs of grass resemble an overgrown battlefield. Later there are close ups of flowers, waves foaming onto a shore, dawn-tinted clouds. A sudden flurry of snow behind a gauze is breathtaking.

Other images fare less well. What appears to be a information billboard for a charity helping the victims of Srebrenica appears, jarringly, in the background of one scene. It’s not clear whether it’s intended to be an actual billboard in the world of the characters, or a garish reminder of recent horror.

A grave, which appears suddenly and shockingly in the snowscape, contains a stage lift, which the pallbearers walk across to get into position, before the lift descends to make room for the casket.

These lapses in logic aside, the effect is soothing because the images are so starkly gorgeous; and surely, this work should not soothe. Britten famously used Owen’s words “in war, all a poet can do is warn” as his inspiration. Tillmans isn’t warning, he’s painting.

There’s no doubting that a stage full of corpses will always be an arresting image. But there are diminishing returns here. By the fifth or sixth time the chorus settle themselves down, the effect has lost its power. And it’s always a gentle and smooth descent: where is the sudden, obscene crack-and-fall of a gunshot?

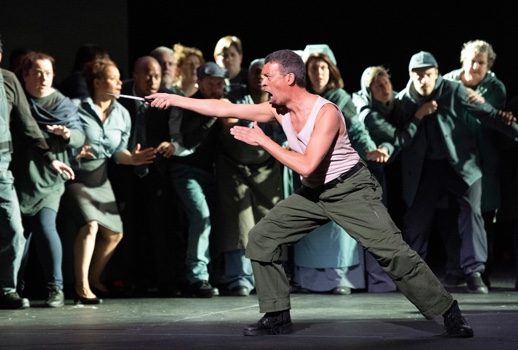

If you’re choosing to stage a concert piece, the storytelling needs to be better than this. What we end up with is a series of, essentially, moving tableaux of displaced, or mildly bellicose, or stoically grieving people.

Stage movement often mirrored the libretto in an unhelpfully on the nose, route-one kind of way, most notably when the devastating last line of “Abraham and Isaac,” “And half the seed of Europe, one by one” is flashed up in block capitals on the screen while the tenor soloist walks around a crowd of children, each one lying down as he taps them on the head. Get it?

When the text wasn’t being hammered out, it was ignored. A staged production of this work really has to address the fact that it’s performed in two languages. Emma Bell’s soprano soloist, traumatised in a simple red dress and dignified in mourning wear, wandered in and out from time to time without us really knowing who she was or why she was singing in Latin.

For all the power and passion of Bell’s performance, she was also asked too often to ignore the text she was singing. A moment where she consoled a bereaved soldier was truly touching, but the fact that she was singing “Judicandus homo reus” at the time was a little confusing.

Bell was in secure voice. The vocal problems that have been noted here in the past seem to have been growing pains—this isn’t a lyric voice any more. A slightly hollow centre to the tone quality and an incipient squall up top suggest some of that growth may have been forced, but Bell hurled out her tricky part fearlessly, and made some exciting sounds.

She also managed to create some touching moments, in some ways despite rather than thanks to the production.

All three solo performers, in fact, were dramatically excellent, and it’s worth mentioning at this point that it’s exciting to live in an operatic world where above-average acting ability is expected rather than a bonus. This isn’t “nobody acted before Callas” nonsense: it’s lived experience.

There have always been excellent operatic actors, but to expect quality across the board was to invite disappointment when I started going to opera thirty years ago, and it’s a change worth celebrating.

David Butt Philip and Roderick Williams both sang exceptionally too, with liquid beauty of tone and the lieder-singer precision of their predecessors. Butt Philip sang what is for me the emotional centre of the score, “Move him into the sun” with a delicate brokenness. The hardest heart would have cracked at his “Was it for this the clay grew tall?’

Williams, too, has a beautiful sound and colours the voice expertly. The two made something very special of “Strange Meeting’, which would have made perhaps even more impact if we hadn’t had a “here we go again” moment with a mass lie-down from the chorus.

Not their fault, of course, and they were on stellar form throughout, augmented by the specially-assembled chorus from Porgy and Bess and the Finchley Children’s Music Group, who managed to avoid both preciousness and coarseness, the Scylla and Charybdis who threaten children’s choirs.

Martyn Brabin, in the pit, tended to eulogise rather than horrify, but that was in fitting with the aesthetic of the production, and there was a clarity and precision to the music-making from all concerned. I could even hear all the words, which in the muddy puddle that is the Coliseum acoustic is a rare treat.

I’m probably being too harsh on this production. There’s no doubting it’s a perfectly-executed version of Kramer and Tillmans’ vision, it’s just that I’m not mad on the vision itself. Many others will have been stunned, moved, and devastated by it, I’m sure.

But for this reviewer, things felt sanitised. Where Britten offers us a fragile note of comfort at the end of the work, this production gives us a huge image of a technicolour window, open to reveal vibrant greenery. Requiem aeternam dona eis, domine, and Make Our Garden Grow.

It’s beautiful to look at, but when transferring a work like this from a concert hall to an opera house, we need things to think about too. And a third venue comes into play when considering the production: it’s a portrayal of the horror, the grief and the futility of war, as sensitively and earnestly imagined in a clean, comfortable rehearsal room.

Comments