They let their golden chances pass them by.

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel is a work of inarguable genius, so perfectly crafted that it almost feels impossible to mess up. If you don’t believe me, then head on down to the Imperial Theater, where Carousel is receiving a Broadway revival in a simple, cautious production that still manages to pack an emotional wallop.

Based on the play Liliom by Ferenc Molnár, the musical charts the imperfect love between Billy, a rough and sexy carnival barker, and the naïve Julie Jordan. When Julie becomes pregnant with Billy’s child, Billy attempts a robbery to provide for his nascent family. Unfortunately, his mark pulls a gun on him, threatening to send him to jail.

In desperation, Billy cuts himself with his own knife and dies. In an afterlife, Billy meets the Starkeeper, an angelic figure who offers him a chance to return to the living, to make things right with Julie and his daughter Louise.

Set on the coastline of Maine, the score and book evoke the inevitability of love and sex. In probably the most erotic scene in all of musical theater, as Julie and Billy’s ambivalent feelings for one another begin to surface, flower blossoms rain down on the couple from the trees above.

The petals flood the scene with sensuality, a symbolist gesture to the body’s own timely ripening. The music swells, and the lovers each question what life would be like “If I loved you.”

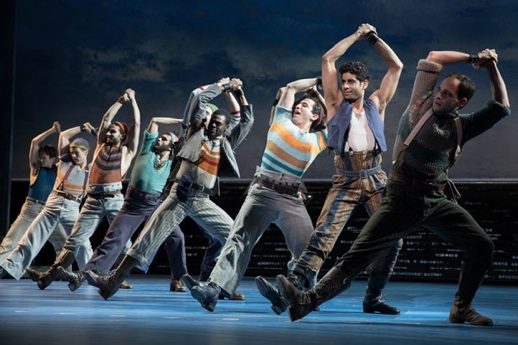

Throughout the musical, fisherman and millworkers leap and strut like birds in their mating dances, with muscular, athletic choreography by New York City Ballet’s wunderkind Justin Peck. Peck’s stunning work tightens the focus on the power and grace of the human body, highlighting the ways that biology and reproduction (one of the many carousels referred to by the title) provoke one into motion.

At a recent performance, Jessie Mueller and Joshua Henry developed the right combination of pull and push to make Billy and Julie’s chemistry dynamically compelling. Where Henry’s Billy was erratic, sensual, and intense, Mueller’s underplayed Julie was quietly pathetic. Mueller was especially effective, her crystalline soprano caressing each elegant phrase.

In contrast, Henry felt a bit vocally miscast. His voice was warm and round in the lower register, but as he launched into the more demanding passages of “Soliloquy,” a troubling strain on the higher notes started to creep in.

And then there was the idiosyncratic Reneé Fleming as Julie’s cousin Nettie, who swooped and scooped her way through her show-stopping numbers, displaying that gorgeous instrument in all its warmth and beauty. Fleming was especially striking during the devastating “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” hitting notes of bittersweet optimism within the most shattering of circumstances.

The rest of the cast turned in distinct and detailed performances. Amar Ramasar’s Jigger Craigin managed to be both menacing and elegant, no mean feat in high-waisted pants. And Margaret Colin was a campy, acerbic Mrs. Mullin. Brittany Pollack, as Julie and Billy’s daughter Louise, thrilled in her Act II ballet, where Peck’s exuberant choreography allowed her to convey simultaneously the character’s alienation and budding sexuality.

However, Jack O’Brien’s direction seemed a streamlined disappointment. Besides the opening, which moved from the celestial domain of the Starkeeper to the carnival grounds in Maine, the best that can be said is that the direction was clean and concise—at worst, merely perfunctory. While not a revelation, his artistic vision was detailed enough; but with material that one can’t screw up, how much of an accomplishment is this really?

To critique a live performance of a perfect text is a difficult task. How to see beyond the material and into the worthiness of the work that bodies it forth? Hammerstein’s words and Rodgers’ music, in anyone’s mouth, maintain the power to move. That is, if the text remains unaltered.

Domestic violence, a theme throughout the musical, is messy subject material—no one would argue with that. And this messiness makes the musical difficult to cleanly graft onto political movements.

As much as one wants to force characters like Julie and Billy into manageable categories of victim and monster, Carousel refuses such easy formulations, practically rubbing one’s nose in the complexities of love—its power, its inevitable pull, not to mention its denial of politics, its refusal to play nice, to be useful or even moral.

One thinks of Oscar Wilde, writing in his preface for The Picture of Dorian Gray: “No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.” And as one judges Carousel by this metric, one finds a (to quote Wilde again) the “perfect use of an imperfect medium.”

Carousel is not here to comfort our moral self-righteousness. It instead asks us to look deeper, with greater attention, at the complexities of human experience—both its brutish, unpardonable cruelty, and its sublime beauty.

But this is a risk the current Broadway production of Carouselrefuses to take. Instead, it offers us a watered down, more palatable version of the narrative. One that won’t ruffle any feathers, or push its viewers into any uncomfortable moral positions.

While I can understand the desire to simplify and dismantle the offensive impressions of Carousel, to soften its bite, I’m appalled at the current production’s cowardice, it’s inability to let audiences wrestle with what’s really at stake. It’s an insult to viewers; the dumbing down of American audiences continues.

Louise is startled, but unhurt by the incident. The fact that his hitting did not hurt her shocks her more. When Louise asks her mother if it’s possible to be hit and not feel a thing, the libretto has this exchange:

LOUISE: But is it possible fer someone to hit you hard like that, real loud and hard, and not hurt you at all?

JULIE: It is possible, dear—fer someone to hit you—hit you hard—and it not hurt at all.

Julie’s speech has been cut from the current production on Broadway, perhaps because it can be interpreted as an apology for domestic violence.

But even if Julie does make an apology for domestic violence, as a victim of domestic violence, is it artistically prudent to deny this perspective simply because it’s not politically expedient, or even palatable? Isn’t Julie allowed to be wrong, damaged, and fucked up—traumatized by her situation, forgiving Billy’s unforgivable crimes? And if she does, does this necessarily mean that this is a perspective endorsed by the creators?

Such demands of the text—that it play nice, that it bolster our moral maxims—insist on art as guidance and prescription. It’s as if the team behind this current production is telling victims of abuse how they’re supposed to feel about their experiences, instead of letting the character speak for herself.

Art is not here to produce a political movement—certainly it can reverberate politically, but it is not here to be sympathetic to ethics. If it does have any purpose or task, it is to be beautiful and artful, shining a blistering light on what is mysterious, what is magical, what is painful.

Photos: Julieta Cervantes

Comments