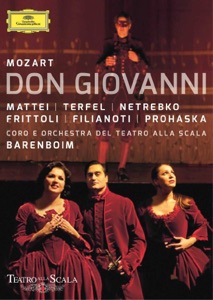

The Canadian Robert Carsen would appear to love the theater to the point of fixation. In a three-decade career as one of opera’s busiest directors, he has returned again and again to the device of the meta-theatrical frame. While by no means interchangeable, Carsen’s productions of Mefistofele, Les contes d’Hoffmann, L´incoronazione di Poppea, Capriccio, Tosca, and Ariadne auf Naxos all toyed with similar theater-within-theater tropes and motifs, and so does La Scala’s 2011 season-opening Don Giovanni, newly released

on DVD/Blu-ray.

When I saw this production’s glitch-filled cinema broadcast in December 2011, I left with mixed feelings. I knew I had seen an attractive, engaging, and well-cast Don Giovanni, better than most of what I had seen done with Mozart and Da Ponte’s opera in recent times. But I felt it had come too easily to its creator and that he was treading too-familiar ground.

I remarked that he could do to take a long break from red/gold curtains, ersatz “backstage” sets, characters entering through the auditorium or climbing onstage from the orchestra pit, characters operating the curtains themselves. The video release has provided me an opportunity to revisit that opinion, and I find that time has been kind to the production. If Carsen’s response to this material was a predictable one, any artist is entitled to his hallmarks, and the approach this time is suitable and witty in application.

Costume designer Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s clothes (gorgeous work for aristocrats and peasants alike) evoke the mid-20th century, and Carsen and set designer Michael Levine subtly suggest theatrical methods of 50 years on either side—a century of Don Giovanni stagings in one evening. Lighting, by the director with his longtime collaborator Peter van Praet, is exquisitely calibrated.

Videographer Patrizia Carmine, who can err on the side of artiness, goes for clarity this time, one of her few indulgences being a swirling, disorienting close-up of marks on a stage flat for the Don’s conquests, as Leporello lists them. Carmine gives us a lot of welcome views of the whole stage…and of the auditorium when the performers are scampering around in it, which they sometimes are.

After an interminable opening-credits sequence (really, skip past it) and the Italian anthem, the opera begins with a promising, much-celebrated flourish. Don Giovanni’s portrayer runs down the center aisle, takes the stage on the opening D-minor chord, and yanks down the red curtain to reveal a mirror that reflects him and the auditorium behind. He considers his own reflection, then turns to stare down the audience before vanishing again into darkness.

Levine’s sets over the following three hours are variations on the curtain and the auditorium. Some are very simple flats (moved around by “stagehands”); others are more elaborate. The guests at Giovanni’s party wear costumes and masks that appear to have been fashioned from the theater curtain.

The notion of Don Giovanni as ordering figure, established before the first chord has subsided, is further developed throughout the opera. The Don effects his escape at the end of Act One by signaling for the curtain to be closed, and as it closes, it knocks the weapons from his pursuers’ hands. When the Don is not needed on stage, he sometimes hangs around and observes from a chair like a director. He and Elvira’s maid sit, backs to the audience, watching the reconciliation of Zerlina and Masetto. The Don seems pleased with this scene, which he helped bring about by clobbering Masetto. Our libertine even reappears, still in control of the others’ destinies, during the moralizing epilogue.

Carsen collaborated with the cast for some intriguing takes on familiar scenes. Donna Anna when first seen is obviously enjoying herself, rolling about in bed with Don Giovanni. The pair’s threats and their talk of escape and identity are played ironically, or at least mean something different from what is traditionally understood. Anna comes into focus as a complex, duplicitous figure. Her initial failure to recognize Giovanni at their second encounter may be accounted for by her dark glasses as well as her numbness and grief (the scene is staged with visual flair as the Commendatore’s funeral).

Elvira initially is thrilled to see Giovanni, and her first angry words to him about abandonment are just a playful scold. The real anger only comes later. Her reactions to Leporello’s “Madamina, il catalogo è questo” (in a lively staging) tell us things about her. When Leporello gets to the part about the Don’s fondness for short women, Elvira scrunches farther and farther down toward the stage, as if trying to minimize her own height. The moment passes quickly, but it is funny, then sad and truthful. When Leporello’s aria is over, this Elvira does not flounce off in indignation; she crumples, devastated.

What I had thought in 2011 was a weak spot, the troublesome stretch in the middle of the second act in which Da Ponte provided very little story, now strikes me as more successful. Carsen is so hands-off in staging the second-act arias of Ottavio, Elvira, and Anna that I felt I was watching, in those parts, a Mozart mini-gala from an opera house. It really plays that way, with formally dressed singers striding downstage to belt it out in front of sets quoting “the theater,” then exiting to applause. This is a bunt, yes, but (if I am right about the intention) a clever one, and not a bad way of dealing with one of this opera’s challenges.

In the title role, Peter Mattei exudes sunny self-assurance and a belief that things will go his way. There is not a trace of cynicism or frustration. This is a young playboy Don Giovanni, more lover than fighter. He attempts to ward off the Commendatore by tossing a pillow at him, and the fatal stabbing looks like dumb luck. Mattei’s singing is a pleasant dream, with sunlight and warmth in the tone to match the good-natured personality. In “Deh, vieni alla finestra,” he is daring with dynamics, taking his voice down to the slenderest thread, but holding the audience with beautifully spun line.

Twenty years and adventures in changing repertoire had worn some nap off of Bryn Terfel’s bass-baritone by 2011, and his address is gruff, not without some braying and neighing. But he presents a plausible and interesting Leporello, a harried older servant who now finds less amusement in his young master’s escapades but sees limited options for himself.

Giuseppe Filianoti manages cautiously as Don Ottavio, singing as though fearful of putting pressure on a fragile voice. There is strong musicality to the performance he is shaping in his head, but what actually comes out is tight and not so gratifying to hear.

The other weak link is Kwangchul Youn’s phlegmatic Commendatore. The character gets clever staging (in the graveyard encounter, Youn faces the stage from a center box, flanked by Italian government dignitaries), but this can only goes so far. The short, one-note part needs a commanding sound, presence, or both to make an effect.

There is a good amount of flesh, spirit, and the devil in all three of the formidable women. Anna Netrebko is a vixen styled à la Elizabeth Taylor (again.) Her Donna Anna is a demonstration of her expected virtues and vices in Mozart circa 2011. She is dragging a now-heavier voice through the music rather than being completely on top of it, she overshoots a few pitches, and one has to hunt for consonants. In her favor, she brings a compelling, combative attitude to the character, she means what she says and phones nothing in, and her sound is healthy and glamorous.

Barbara Frittoli, playing an especially desperate Donna Elvira, looks smashing in the black slip to which the director has her strip down more than once. She makes more of recitative than anyone else in this cast, tasting and savoring Da Ponte’s words. In both recitative and aria, she is sensitive to color, shade, and accent. Although low notes are weak (an issue as far back as an excellent 1996 Fiordiligi with Abbado, also on DVD), and the tone has a beat and general wear to it, her stylish and caring performance is an asset.

Anna Prohaska and Stefan Kocan provide considerable attractions lower down the social order as the peasant couple. This time, Zerlina really looks like a young girl, gamine and small-boned, and Prohaska plays her not too smugly or too cutely, but like someone just beginning to realize that her charms can get her out of (or into) tight spots. Both arias are tender, seductive, and beautifully phrased. Stefan Kocan, who at the Met often seems questionably cast and obliged to manufacture a grave-old-man sound (Ramfis, Konchak, the Commendatore in this opera), is just about ideal for Masetto, and I have never heard him sound better. He and Prohaska have chemistry and roll about very sexily.

The DVD release has scrubbed out the heckling and booing of Maestro Daniel Barenboim from the Milanese public. You may be moved to supply your own. No matter what age you are, this is “your father’s Mozart,” a stodgy, lumbering reading unworthy of opening night at a major house. There was not a movement over two long acts that made me think Barenboim had risen to an important occasion with music-making of much distinction. The high points were those in which the orchestra receded to a level of such basic accompaniment that I was not noticing it, and a list of less famous conductors who could have done as well or better would match the Don’s catalog for length.

By the ultimo, the other characters in this Don Giovanni seem both more real and less vital than Don Giovanni. Whatever their final resolutions, they need this elusive Eros-like figure and will continue to “pursue” him through their romances, jealousies, misunderstandings, and vain hopes. The chic production by Carsen and his excellent team makes it a pleasure to stumble along with them in the dark for a while, even if we come out the other side having learned as little as they have.

Comments