For centuries, European history has provided source material for operas, but it would be generous to say that history comes alive on the operatic stage. More often it is frozen into exhibits of dubious validity, and the power must come from the music. Wars of hundreds, even thousands of years ago must have been ignited by fierce passions, and no doubt there were unspeakable acts committed in their course. But in historical operas of the standard repertory, the material tends to be safely distant from the experience and understanding of most of the audience.

How many attending the Met’s current production of Il trovatore have a point of view on the actual 15th-century conflict with which its characters are preoccupied? Some who typically complain about such things do not even realize that the Met’s Trovatore is a 19th-century update. It still looks reassuringly “historical,” after all.

In the late 1960s, the Polish-Jewish composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg collaborated with librettist Alexander Medvedev on The Passenger, which inspected a still-fresh historical wound. The Polish author Zofia Posmysz, still with us today at the age of 92, lived to tell of the horrors of the Auschwitz and Birkenau death camps. One day in 1959, walking in the Place de la Concorde in Paris, she thought she heard the unmistakable shrill voice of a female camp overseer.

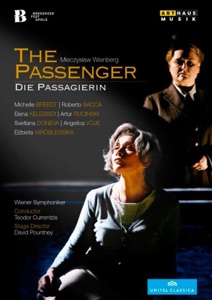

She quickly realized she was in error, but her experience formed the seed of a radio play, which became a novel, then a film, and ultimately Weinberg’s opera. Soviet authorities denied the opera a planned Bolshoi premiere in 1968, and it lay unperformed until it was played in concert form in Moscow in 2006. The 2010 Bregenz Festival gave The Passenger its first stage production, and Arthaus’s new DVD is the second release of same.

Posmysz’s most inspired stroke in her story was to transfer her own alarming postwar experience to the female camp overseer. The main character, 37-year-old Liese (mezzo-soprano), is happily married to Walter (tenor), a West German diplomat 13 years her senior. Liese has never told her husband of her past as a camp guard 15 years earlier.

Aboard the ocean liner that is taking the couple to Walter’s new posting in Brazil, Liese believes she sees a woman, Marta (soprano), who was a Polish inmate at Auschwitz. She tells herself this is impossible, more than once asseverating, “No one came back from the Black Wall.” She bribes a porter to find out more about the woman, and eventually confesses her own history to Walter. Walter is horrified, less on moral grounds than in mind of the ramifications for his diplomatic career should it come to light that his wife has SS associations.

In flashbacks, as Liese recounts her time at Auschwitz to Walter, we learn that Marta was not just a number to Liese. “Proud” and “obdurate,” she held strange fascination for her captor. Marta’s fiancé, a violinist named Tadeusz (baritone), was another inmate in the gender-segregated camp. Liese offered Tadeusz secret access to Marta, not out of kindness but for manipulation. Marta was an admired figure among the female prisoners, and Liese wished to have her in her debt and under firmer control.

Tadeusz infuriated Liese and signed his own death warrant by refusing the offer. Tadeusz was then forced to perform a concert at which he would play the commandant’s favorite waltz, and Liese cruelly insisted that Marta attend. Tadeusz instead played a Bach chaconne, an insolent reminder to the SS of the descent of the German nation and its culture. Tadeusz’s violin was smashed and he was beaten and dragged away, never to be seen again by Liese or Marta.

Back in the opera’s present day, Liese and Walter have their fears reignited when the porter reveals that the mystery woman he had first reported to be English is, in fact, Polish. Liese and Walter, who have stayed sequestered in their cabin since the initial sighting, finally decide they have nothing to fear, and they attend a dance on board. But the mystery woman requests of the bandleader the waltz that Tadeusz had refused to play for the commandant, and Liese shrinks back in terror.

It is never confirmed that the woman, who wears a veil and carries herself like a Shakespearean ghost, is Marta. She and Liese exchange no words in the present day. The musical request could as easily be a coincidence as a message. But it is clear that for Liese, there can be no closure, no deliverance, no escape.

The opera ends with an epilogue delivered by Marta, and the viewer must decide whether she is a flesh-and-blood survivor or a spirit from beyond. (In the Bregenz production, made to look older, with her now-gray hair grown out and stylishly coiffed, the epilogue’s Marta resembles Ms. Posmysz.) Marta sings of remembering her friends, her fiancé, and her persecutors. She can neither forgive nor forget.

The rediscovery of The Passenger in the 21st century comes at a time when the Holocaust is dramatic ground far more heavily trod in books, plays, television dramas, and films than it was when Weinberg and Medvedev did their work almost 50 years ago.

This is not to say it has lost its power. One would have to be very hard of heart not to be moved by the barracks scene that closes Act One, our first long look at Marta and several supporting female prisoners. The composer and librettist take us up close and show us the ways in which these women have responded to their plight: madness, religious devotion, anger, fear, courage, despair. One young woman calls out for her mother. This long interlude is as wounding a scene as anyone has ever thought to put on the operatic stage.

But what makes The Passenger most worthy of consideration is the power of Weinberg’s music and the specificity of the opera’s interpersonal drama, and in one case (only one) its characterization. Weinberg reportedly considered The Passenger, one of his seven operas, to be his most important work. If it has a close musical cousin in more familiar repertory, it is Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

Like Shostakovich, who was a friend and admirer, Weinberg alternates martial, heavily percussive music with lyrical outpourings as well as forays into arch, italicized vulgarity (the commandant’s beloved waltz). One masterstroke is Tadeusz’s initially unaccompanied Bach chaconne for violin, which the orchestra gradually joins for rich embellishment before the SS thugs bring the episode to a violent conclusion. One does not want to let go of this music… in a way, making Tadeusz’s point.

The opera’s figure of fascination is Liese, the Nazi overseer, 22 in the past and 37 in the present. This is a potential dramatic tour de force for a mezzo-soprano, the kind of assignment in which even the same singing actor could find many approaches through different productions.

Like many real-life collaborators, Liese makes a case for herself by talking about the atrocities in which she did not participate, about the small kindnesses she bestowed. But without irony, she also tells her husband, “These people [Jewish camp inmates] know how to hate, Walter. All of them.” Fifteen years after the war ended, she has the temerity to feel not only threatened but aggrieved.

An early flashback in which Liese is leered at and objectified by male SS colleagues, although it feels like a throwaway, is there for a reason. Unlike Marta, who has friends and a devoted fiancé, Liese is not respected and loved by those around her. It is apparent that she envies Marta and Tadeusz their relationship, but as the opera goes on, we begin to ask which one of them she wants to be. She calls Marta “the Madonna of the camp” and takes peculiar interest in the physical details of reproductions Tadeusz makes of Marta in sketches and carvings.

The first words we hear from Marta reflect bemusement that Liese is constantly staring at her. In the Bregenz production, when Liese reveals to Marta that both she and Tadeusz will pay for their ingratitude to her with their lives, she leans in so close to Marta that their mouths are about an inch apart; a kiss is threatened.

There is a great deal to unpack in Liese: guilt, denial, obsession, questions about the very definitions of conscience and remorse. I wonder if any one production can do everything it is possible to do with her. Fortunately, her first onstage portrayer, South African mezzo Michelle Breedt, is a compelling and energetic performer who is up to the task.

She has an interesting physical presence, especially in the camp scenes, in which she saunters around modeling a prison wardress’s “hardness” that keeps slipping. She sings tirelessly and with nuance, and she goes as far into the character’s messy psychology as anyone could in the circumstances. Forty-three at the time, she is convincing as the younger and older versions of Liese.

Best of the other cast members are rising baritone Artur Rucinski, who floods the indomitable Tadeusz’s music with amber tone, and Svetlana Doneva as the Russian prisoner Katja, who sings for her friends a beautiful a capella folk song that stops the show.

There is a well-judged, “correct” turn from veteran tenor Roberto Saccà in the unrewarding part of the bourgeois husband, Walter. Unfortunately, soprano Elena Kelessidi’s Marta is marred by instability and tonal edginess. Her hardworking dramatic performance, in what could be the opera’s other great role, does not locate a character in the nobly suffering object.

In the years since 2010, David Pountney’s strongly theatrical production has traveled to several European and U.S. venues, with stops in Houston, Chicago, and New York (the Park Avenue Armory), and an upcoming Florida Grand Opera premiere. Medvedev’s original libretto was in Russian, and Pountney oversaw a multilingual revision incorporating German, English, Polish, Yiddish, French, Russian, and Czech text.

Johan Engels’s set design works a transparent heaven/hell concept with upper and lower levels. The ocean liner is above, and the ship itself and all of the costumes and furnishings are conspicuously rendered in spotless whites and creams, reflecting the whitewashing of present and past by Liese and her kind.

Scenes of the past take place in the grimy hell below, where the lighting and the inmates’ clothes have dingy yellowish/sepia tints, and smoke hangs like fog. Eventually the smoke makes it to the upper level. Like memory, it cannot be suppressed. When the mystery woman requests the waltz from the ship’s orchestra, the mortified Liese is literally backed down the stairs, where she (in a visual echo of Marta’s ordeal 15 years earlier) is forced to watch Tadeusz’s fateful recital.

The whole undertaking is elevated by the literally slashing authority of the young Greek conductor Teodor Currentzis, leading the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. The assaultive pages of Weinberg’s score have real bite and thrust under Currentzis’s characteristic flailing, but the orchestra also savors delicacy and stillness. When two inmates talk in the dark and express despair and optimism, respectively, Weinberg’s perseveration on the despairing theme tells us which woman will be proved correct. “It hurts to be human!” she sings. Indeed.

A 30-minute bonus documentary charts the production team’s tour of Auschwitz, and we hear from Pountney, Currentzis, Engels, Posmysz (spry and looking wonderful in her great age), other production and cast members, and some Weinberg scholars.

Annoyingly, the English subtitles in the documentary do not continue when a subject is speaking English, and a superimposed German audio translation makes all but their first few words inaudible. Otherwise, it is a valuable extra, especially when we see Posmysz inspecting a model of Engels’s set.

The opera would get no recommendation from me if I felt it were merely “good for you,” something to be lauded because it is about an important subject and you would feel better after having gotten through it. Like any work of art, to be recommendable, it must be good, period. It is. It should be seen and heard, and the Bregenz Festival’s pioneering effort did justice to it.

As much as The Passenger is a “historical” opera, it is a ghost story, one that survives its stretches and implausibilities (Liese relates to Walter much that she could not have witnessed). I think that everyone who has lived for a few decades has had the experience of seeing someone coming closer who actually vanished long ago. You blink and realize it was a trick of the light and shadows, abetted by memory. The ghosts are never really there, yet they are always there, waiting for the next time they can be let out of our heads.

Comments