I was once accused—by my own mother, mind you!—of having too many recordings of Verdi’s Aida. The blistering audacity of that recrimination did get me to thinking: How many recordings of Aida is too many?

I mean, you’ve got the old classic you cut your teeth on. Then there’s he one where the tenor and the mezzo are really the only good thing going. And, of course, the one with your favorite soprano in the title role, the remake when she switched labels, and then the four pirates. Don’t forget the one with another favorite soprano, but this time she’s Amneris and it’s awesome.

Then you’ve got your fave “little performance that could” from behind the Iron Curtain with a cast whose names bring on an unintended stutter when pronunciation is attempted. The original instrument version? A half dozen other pirates with one star you love(d) surrounded by singers that haven’t heard from their agents since? Then, finally, the recording you cherish where the star soprano singing the role of the Priestess, in a guest cameo, contributes the single greatest performance of her entire career.

That was all vinyl, of course, long gone and worn out. Nearly all were repurchased on CD and then some. But those first CD’s issued all those years ago at the dawn of digital technology were flawed. Acoustics were clean but overly-bright with maybe too much compression of the aural image. Naturally as the industrial science improves the recording companies, no fools they, re-master nearly everything and bring it out again at (usually) bargain prices. Or they can go the other route (Warner Classics, new home of Maria Callas!) and bring out the Rolls Royce editions with bells, books, whistles, oversized boxes and assorted perfumed remembrances.

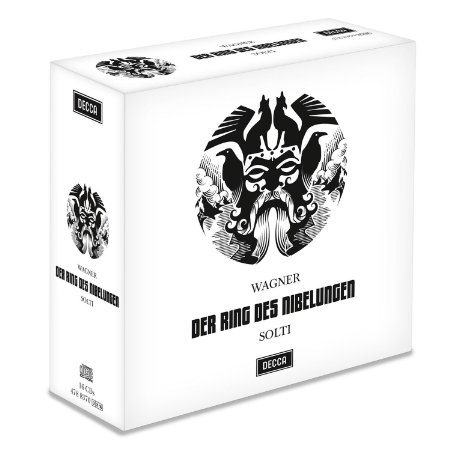

Such was the case when Decca remastered in 2012, for the third time since 1984, their ne plus ultra recording of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen produced by John Culshaw with the help of Christopher Raeburn and conducted by Georg Solti. Why not? It’s reportedly sold a million copies. That means, presumably, that roughly the same 200 thousand people have been rebuying it with each new iteration.

For this deluxe issue it came in a large LP box (14 pounds, I warned you) and included the recording spread out over 17 CDs. Included were Mr. Culshaw’s very entertaining and informative book about the recording process, Ring Resounding, the BBC documentary on the same topic, The Golden Ring, an actual printed libretto (a what?), Deryck Cooke’s Ring primer on 2 CDs, a facsimile of one of Solti’s working scores with his markings and explanations of said markings, plus photo art prints of the recording sessions.

The pièce de résistance: implausibly scrunched onto a single Blu-ray disc, the entire 14 hour and 30 minute performance. Numbered and printed in a limited edition it sold for such a high price that it qualified for Amazon’s six-month financing program.

I have never owned the Solti Ring. After all I was an opera fan birthed at the dawn of digital sound and my first Ring recording was Marek Janowski’s digital Die Walkure which was packaged beautifully, you may recall, in (faux) red velvet. Also it was remaindered at $19. I got my first complete Ring through a record club offer with the whole Met studio version for $60, boxed with the librettos.

Bargain-hunting over the years, I made a killing on the re-mastered Goodall in English (used), the Salzburg/Berlin Karajan (Amazon mispriced!), the Haitink with the Bavarian Radio Symphony (no-frills re-release) and that original Janowski reissued now for $29.99 total in packaging that imitates the original LP’s. It was like shoplifting with a receipt!

But the Solti? I’ve heard bits and pieces of it over the years and I always found the recorded sound quaint like a 1950’s Cinemascope film score and obviously manipulated. Also with some of the larger voices (yes, I’m looking at you Birgit Nilsson) the microphones seemed almost inadequate to their task. It was your grandfather’s Ring. Everyone on it was certainly retired and most of them dead. Mr. Culshaw, whose book I thoroughly enjoyed and recommend, had this Sonicstage “theatre of the mind” going on and it had very little to do with capturing the sound of a live performance and more about making a performance specifically for the listener’s living room. Now that’s a grand idea, but where am I going to put Fafner?

Three years have passed since the luxe reissue and our friends at Decca Classics have finally shown some pity to those of us still enjoying the economic downturn and released just the CDs in a tidy budget box with the briefest of synopses in a booklet with some production notes, the 2-disc Cooke lecture, and a CD-ROM with full libretto and translations. Then I saw it online and on sale for $39.99!

Naturally I re-read Mr. Culshaw’s opus in anticipation whilst tapping my foot waiting for the postal carrier to arrive. It is a fascinating book for anyone who’s curious about what goes into preparing and producing a classical recording. We hear of contract negotiations, the egos involved, the mishaps, and lucky breaks: the difficulty in grooming a Siegfried specifically for the project only to be disappointed; Nilsson’s insistence on recording her Isolde before she’d even consider the Brunnhildes; the merry dance between Mr. Culshaw and the legendary Kirsten Flagstad who he wants for the sake of posterity to singFricka on the recordings.

Great, great, singers, the likes of Gustav Neidlinger, Set Svanholm, Claire Watson and Hans Hotter, were given the opportunity to document their portrayals for history. It is this sense of history now, more than anything else, that completely pervades and illuminates this project.

Then there’s the participation of the Vienna Philharmonic and the conducting of Solti. The playing is at times far rougher than I expected from these urbane Austrian gentlemen primarily known for their sleek sonority. Goaded on by the maestro to ever-higher levels of fervor, they achieve something elemental and primitive in much of these performances which is most befitting to the story they’re telling.

Of course, there’s plenty of their renowned tonal beauty in the bucolic sections of the work (please, someone wake me when Siegfried finds the rock) but when the fantastical elements of the story are invoked it becomes a much wilder ride than you’d expect. You often hear the coarse sound of the bows in the string section and there are times when the horn playing verges on the untamed.

Liner notes in the back of the booklet explain that this transfer was not made from the original tapes, which have sadly disintegrated past their use, but from the 1997 digital re-master that was overseen by Decca engineer James Lock, who had been a junior member of the team back in the day for Walkure. This transfer utilized a process known as CEDAR (Computer Enhanced Digital Audio Restoration System) and was indeed made from the original analog tapes.

Although the CEDAR process was generally reviled as a sterile whitewash for small noises and undertones Lock’s skillful use of it did generate, what is considered, the best digital transfer until now. The liner notes also point out that a missing quaver at Donner’s entrance in Scene 2 of Rheingold has been restored from a previous mastering. (Whew!)

It’s immediately apparent from the famous E-flat that bubbles up from the bed of the Rhein that the undertones have not only been saved but enhanced. The entire soundscape has been widened considerably and although I still find the sound too “styled’”at times, the clarity is certainly much better than I have ever heard it. The knob-fiddling (like the blatantly apparent overlay of the anvils in the descent to Nibelheim) seems to become less and less conspicuous as the cycle progresses as well. The Valkyrie sisters, however, still are Ho-jo-to-ho-ing away in the ladies’ loo down the hall.

As to the voices, I can only say that I’m sure nothing will ever come close to faithfully representing the impact of Nilsson live. However, I think this recording shows her to the best advantage and now with the widened sonics perhaps a truer capture of the glint of that Swedish steel.

Wolfgang Windgassen isn’t to everyone’s taste but listening to him, and how he is occasionally swamped by Solti, is still a lesson in managing the backbreaking role of Siegfried in the last two operas. James King as Siegmund may be a tad solid but Regine Crespin manages to hot things up enough for both of them. Claire Watson is utterly gleaming as Freia and touchingly vulnerable as Gutrune.

Culshaw talks specifically in the book about how Hans Hotter was a necessity as Wotan from a historical standpoint regardless of his age. All the basses are scary as hell and the rest of the cast is just all blue-ribbon authority. An authority that comes across in nearly every facet of this performance. It’s a vibrant, rugged, reading of the work with artists that exult in the demands before them.

Comments