Marek Janowski’s survey of Wagner operas on PentaTone so convincingly captures the pulse and dramatic flow of many of the works that the music-making at times sounds almost effortless.

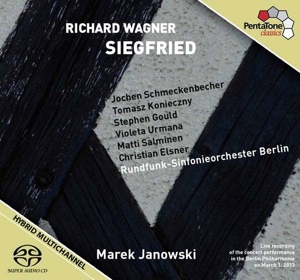

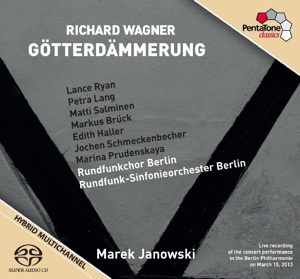

The impression was sure to be tested by the last two installments in the series, Siegfriedand Götterdämmerung, which Janowski and the Berlin Radio Symphony and Chorus recorded in concert performances two weeks apart last March. Though the vocal and orchestral forces remain highly attentive to the veteran maestro’s wishes and the super audio sound vividly captures the acoustics of Berlin’s Philharmonie, the results are a bit of a let down, with overtaxed principals, occasionally underwhelming climaxes and wayward tempi.

Perhaps things were thrown off by insufficient rehearsal time or the decision to cast different Brünnhildes and Siegfrieds for each performance. Or maybe Janowski decided to scratch some Romantic itch and go with a more intuitive approach. Whatever the reason, both performances lack the drive and sense of unity heard in the Ring he cut with the Staatskapelle Dresden in the early 1980s.

Janowski’s light, transparent approach to the music is well-suited for Siegfried, with its comedic exchanges and impressionistic sound-painting in the middle act. While his sense of the narrative arc is acute as ever, there are instances where the music sounds overdriven, as if he’s reaching for a visceral reaction instead of the usual cumulative dramatic effect. The Acts 1 and 2 preludes veer into brassy harshness, and the forging song is taken at an explosive clip that leaves tenor Stephen Gould almost spitting out his lines just to keep up. Never one to dawdle, Janowski traverses the score in 3 hours 47 minutes, neatly fitting the account on to three CDs.

Gould, a compelling Tristan earlier in this series, is a sturdy and confident hero but sounds best when he’s bonding with nature in Act 2, when he can focus on his tone without getting wrapped up in testosterone-driven dramatics. The baritonal voice can turn a bit blustery in the upper register and sounds fatigued by the time he reaches Brünnhilde’s rock in Act 3, depriving the critical scene of some of the necessary passion.

The experienced Wagnerian mezzo Violeta Urmana is an odd choice for Brünnhilde. With most of the dramatic heft in her low and mid-range, she’s challenged by the role’s high-lying tessitura. Add in a pronounced vibrato and a steely, detached approach to “Heil, dir Sonne!” and it’s difficult to develop much connection with the character.

Far more interesting is tenor Christian Elsner, whom Janowski cast earlier as Parsifal and Loge and delivers a refreshingly shtick-free performance as Mime. Full-throated yet capable of great tenderness, he conveys a pathetic gratitude for the scorn and revulsion Siegfried heaps on him and delivers his never-ending complaints with perfect diction.

Bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny plays the Wanderer as a resigned, almost overwhelmed has-been who’s powerless to stop fate from casting his kind aside. Technically secure with a voice that sits perfectly for this role, his performance seems the most limited by the concert format and could have benefitted from more tension in the riddle scene with Mime and a touch more swagger in the spear-breaking confrontation with Siegfried. Still, this is a formidable talent who’s likely to own the role for years.

Among the rest of the cast, baritone Jochen Schmeckenbecher returns as a reliably spiteful, highly musical Alberich while Anna Larsson emits otherwordly, pedal-point tones as Erda. A special treat is Matti Salminen, a veteran of Janowski’s first Ring, who unfurls his familiar, dark timbre as Fafner, aided by a funky echo effect at the entrance. Sophie Klussman sounds distant and generic as the forest bird.

Götterdämmerung

is a similarly hit-or-miss affair. One gets a nice sense of how Wagner’s leitmotifs bubble up, develop and then recede in the musical fabric and how sections like the Act 2 trio of Brunnhilde, Gunther and Hagen hark back to grand operatic traditions. But Siegfried’s Rhine Journey sounds rushed, and his death and funeral music is marred by unexpectedly scrappy playing and balance issues, especially from the overindulged timpani.

As Siegfried, Lance Ryan sounds less a hero than a character tenor, with a strained, colorless tone and a vibrato that spreads noticeably on extended vowels. Though he’s made the role something of a calling card in Europe and has plenty of stamina, the young Canadian resorts to shouting in far too many places and sadly produces some of the most ungainly singing in this entire series.

Petra Lang tackles Brünnhilde’s music much more successfully than fellow mezzo Urmana did in Siegfried. She possesses the rich middle register and secure top notes needed for the second act and impressively powers through the redemption motif in the final scene, intensifying her volume bar by bar. It’s a portrayal that’s equal parts faithful lover and vigorous warrior and quite in keeping with Wagner’s vision of a strong, long-suffering woman who becomes a savior.

Salminen’s sometimes strained, pitchy Hagen is probably not the way longtime fans will want to remember him in the role, though he still injects a chilling gravity into the call to the vassals and more than holds his own in the Act 2 encounter with Schmeckenbecher’s captivating Alberich. Rich-voiced Markus Brück is an effective Gunther, paired with the rather generic but competent Gutrune of Edith Haller. Marina Prudenskaya returns as a very effective Waltraute.

If these final sets in the series do as much to reinforce the value of Janowski’s earlier Ring as sell themselves, they still reinforce the intrinsic value of the PentaTone project. The chamber music-like sensibilities and textural clarity the conductor has brought to these scores shake up notions the way the historically informed performance movement did for the Baroque and classical rep. Though they’re not always the most insightful or original readings, they help us better evaluate the liberties other musicians take with the canonical works.