Could Marek Janowski do for Wagner what the early music movement did for the Baroque and Classical repertory? Though the distinguished maestro is smart enough not to stake any claims of authenticity, his generally fleet, lean-sounding and gracefully shaped interpretations provide a stimulating perspective on works that often invite interpretive overkill.

The latest installments in Janowski’s 10-part cycle of live concert performances with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus are Tannhäuser and Das Rheingold, a pair of dramatically problematic operas that under the right circumstances can benefit from an absence of stage action. Both performances go down like refreshing summertime drinks, with naturally flowing phrases, textural clarity and a strong sense of the narrative arc. PentaTone’s sound quality is splendid. All that’s lacking is an extra dose of power in the musical message and maybe a little more of a personal stamp.

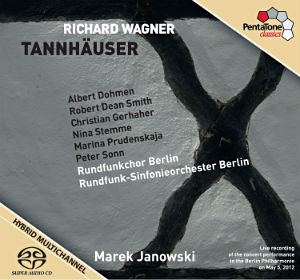

The Tannhauser, from May 2012, is performed using Schott’s newly edited orchestration and serves as a reminder that Wagner’s early phase didn’t just end with Der Fliegende Hollander. There’s a vigorous Romantic character to sections such as the Act 1 finale, and a folk-like flavor in the orchestral motifs that has direct musical connections to Weber. Janowski injects an appropriate amount of pomp in Act 2’s ceremonial segments yet avoids getting bogged down by the work’s lumbering earnestness.

The pacing only feels a little hurried in Act 3 from the Rome narrative on, when dramatic urgency begins to overtake the splendor of the music. Janowski’s Lohengrin similarly focused on speed and precision that, however bracing, sapped some drama from the final act.

Any Wagner performance featuring Nina Stemme commands attention, and the Swedish soprano delivers here as a vulnerable and pure Elisabeth. The vocally exposed Act 3 prayer “Allmacht’ge Jungfrau, hor mein Flehen!” is effortlessly rendered, with mezzo-like colorings that convey a warm, gentle sadness. “Dich Teure Halle” ripples with ecstasy, ending on a somewhat squally high B. Few artists are able to blend lyricism with strong-willed determination as naturally as this diva, even if her full-bodied vocalism is a little ripe for this character.

Russian mezzo Marina Prudenskaya is an intriguing Venus, with an athletic voice that crackles with intensity but doesn’t show an especially wide range of emotions. Her big sound and incisive attack in “Geliebter komm!” is exciting and made me want to hear more. Perhaps some company will engage her for the Paris version of this opera, with its extended interplay between the goddess and title character.

Christian Gerhaher’s text-centric approach and seductive baritone have won raves in his explorations of art songs. His crisp enunciation and restrained legato will make this a Wolfram that’s not to everyone’s taste. I found it an emotionally involved portrayal that placed the character right in the middle of the tragedy. His account of “O du mein holder Abendstern” is beautiful and qualifies as the high point of the performance.

In contrast, Robert Dean Smith’s Tannhäuser is a bit of a cold fish, who could sound more unhinged in the outbursts and convey some torment dealing with his conscience and guilt. Though he has the vocal goods to bring out bel canto aspects of the difficult role and still sound like a Wagnerian tenor, he’s underpowered and not particularly distinctive in the ensemble scenes.

Among the rest of the cast, Albert Dohmann is a sturdy Landgrave and Bianca Reim does well with the small role of the shepherd. The Berlin orchestra is utterly committed to Janowski’s approach, with especially prominent contributions from the woodwinds. The standout chorus is deeply affecting in subdued passages, such as the older pilgrims’ appearance at the beginning of Act 3.

Janowski’s traversal of the Ring begins promisingly enough with a beguiling and vividly detailed reading

of the E-flat figurations in the prelude to Das Rheingold. Unfortunately the forces in this November 2012 performance can’t quite sustain that level of interest for all of the remaining 2 hours and 15 minutes.

Polish bass-baritone Tomasz Konieczny, who’s sung both Wotan and Alberich to great acclaim, has said he views the king of the gods as something of a power-hungry outsider who married well. Perhaps for this reason, his greeting to Valhalla isn’t as poetic as some on record, and his dramatic conception in general seems to key on motivations instead of emotions. The voice still is imposing and even through the registers, with dark, unforced low notes and fine diction. We’ll hear more when he essays Wotan and the Wanderer for Janowski’s Die Walkure and Siegfried.

The light-voiced baritone Jochen Schmeckenbecher nicely captures Alberich’s anger and wounded pride in the opening scene’s encounter with the Rhinemaidens but isn’t forceful enough when delivering the curse on the ring or interacting with Wotan and Loge.

Christian Elsner, who was Janowski’s Parsifal earlier in the series, excels by mining a melting lyricism that is too seldom brought out in Loge’s music, using his pleasant heldentenor to deliver a lovely account of “Immer ist Undank.” Also impressive is contralto Maria Radner, who injects energy into the proceedings during her brief but pivotal appearance as Erda. Her crisp enunciation and almost over-the-top trilling make for an appropriately high-handed earth goddess.

Basses Timo Riihonen and Gunther Groissbock are nicely paired as Fasolt and Fafner and somehow manage to be lyrical yet menacing. Andreas Conrad is a poignant Mime. The most inconsistent performances come from the occasionally unfocused Iris Vermillion as Fricka and soprano Ricarda Merbeth, who sounds overtaxed in spots as Freia.

Janowski and the orchestra support the cast and keeping the action flowing but seem to gloss over some important musical moments. The descent into the Nibelheim is taken at quite a clip, and key junctures such as Erda’s entrance or the gods’ procession into Valhalla sound more businesslike than majestic.

Listeners who know the conductor’s underrated Ring cycle from the 1980s won’t find this installment as compelling or strongly cast. That said, his lucid approach and PentaTone’s vivid sonics will make the remaining three installments of the cycle required listening.