Say this about Oedipus: The character’s got staying power. The mythological King of Thebes, who killed his father, slept with his mother and learned of his crimes through the pursuit of truth, has inspired works by Purcell, Stravinsky, Enescu and Turnage. Add to that list the prolific German composer Wolfgang Rihm, who believed the poor chap encapsulates all that is human in us and pounded the point home in the taut 1987 psychodrama Oedipus that explores the extremes of human emotions.

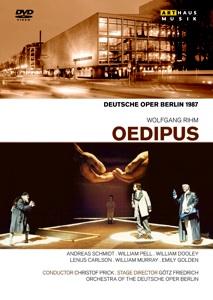

Rihm adapted Sophocles’ tragedy for Götz Friedrich’s Deutsche Oper Berlin at a time when a new generation of German composers was breaking with serialism and dabbling in more expressive musical forms. His version, available for the first time on an Arthaus Musik DVD, retells the tragedy in a 90-minute, uninterrupted series of monologues, flashbacks and tableaus that seem to revel in the steamrolling of human dignity.

Oedipus is portrayed as a kind of marionette controlled by fate, with little exploration of how his own flaws or the exercise of free will contributed to his downfall. Half-sung atonal passages and amplified offstage voices articulating the inner monologues give even the reflective moments a gripping, otherworldly feel.

It was never supposed to be entertaining. Rihm viewed compositions such as Schoenberg’s Erwartung as a starting point for psychological drama and was strongly influenced by the avant-garde playwright-director Antonin Artaud, whose Theater of Cruelty strived to depict truths no one wanted to witness. Small wonder then, that he was attracted to this classic tale in which a savior becomes a corrupter.

In this production, blood, harsh lighting and primitive gestures overlap with pantomimed recollections of Oedipus’ youth. Shrieking orchestral winds and frantic percussion convey torment and a sense of doom as Oedipus is confronted by a steady drip of revelations about his past. By the final tableau, the king is utterly defeated, blinded by his own hand, separated from his children and denounced by the elders of Thebes. He staggers off the stage with a cane and dark glasses, humiliated yet destined to live on.

While it may come off as severe and gratuitously cruel, the work’s structure is ambitious and carefully layered. Short, dissonant musical ideas crisscross, clash and blend in a narrative that has echoes of Webern, Varese and Nono. The orchestra consists only of brass, woodwinds and percussion until the moment Oedipus takes out his eyes, when two piercing violins join the fray.

The fragmentary approach carries over to Rihm’s text, which overlays a heavily abridged German translation of Sophocles by the Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin with text and commentaries by Friedrich Nietzsche and Heiner Müller. Rihm reconceives the classical chorus as 16 solo male voices portraying prisoners, sailors, soldiers and priests, who are interwoven into the plot rather than standing above the action as some kind of supreme authority.

It would all make for a compelling, expressive piece of abstract music, if it was only shot through with more humanity. There’s an impersonal efficiency to the way the scenes unfold — and only a handful of moments when the torrent of expressionism lets up to reveal a flesh-and-blood characterization, such as Jocasta, before she hangs herself. At the end, there’s no calming effect or cathartic release, only the kind of relief one gets emerging from a haunted house full of monstrosities.

Some lusty boos are heard at the final curtain, mingled with enthusiastic cheers for a cast that navigates the difficult, unfamiliar score with confidence. Conductor Christof Prick coaxes an utterly committed performance from the Deutsche Oper orchestra, making the dense, cacophonous accompaniment sound kaleidoscopic while supporting the singers’ shifting rhythms and speech with balance and precision.

Baritone Andreas Schmidt admirably essays the tricky title role and delivers a vivid yet tasteful characterization through his gestures and facial expressions. He was comfortable enough in this kind of rep to later participate in the company’s world premiere of Henze’s Das verratene Meer. American mezzo Emily Golden is equally persuasive as his mother-wife Jocasta, while the tenor William Pell is a menacing Creon. Baritone William Dooley is the blind prophet Tiresias.

The video, originally shot by Sender Freies Berlin and directed by Brian Large, is excellent for its age and captures Andreas Reinhardt’s minimalistic sets and the production’s projections and dramatic lighting. One drawback is the absence of a libretto, which would help make sense out of the more densely scored sections.

Oedipus has only received a handful performances since its premiere run, including a 1991 production at Santa Fe. The most lasting impression comes from its orchestration, which is more inventive and evocative than the stage business. Devotees of contemporary opera will be intrigued by the intellectual approach and the score’s enduring power. Others looking for a more traditional, dramatic treatment of the classic tale may find Rihm’s take opaque and not especially memorable.

Comments