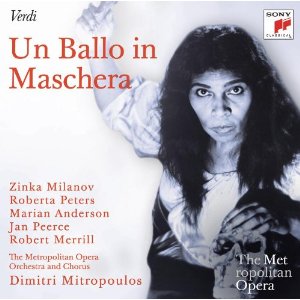

Sony Classical, in association with The Metropolitan Opera, has begun issuing on CD a number of historic Met broadcasts, newly remastered. The first I received for review was the December 10, 1955 broadcast

of Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera, perhaps most notable for the Ulrica of Marian Anderson, who earlier that year made her debut as the first performance by an African-American artist in a major role at the Met.

The real star of this broadcast is the splendid conducting of Dimitri Mitropoulos, drawing every ounce of drama and passion in Verdi’s rich score. Under his leadership, the orchestra and chorus seem to be performing at a much higher level than was normal in the decade of the 50’s. Mitropoulos leads a performance of tremendous sweep and power, yet manages the moments of intimacy with delicacy and precision.

This Ballo is blessed with a genuinely starry cast in roles for which they were duly famous: Zinka Milanov, Jan Peerce, Robert Merrill, Roberta Peters, even Giorgio Tozzi as the conspirator Samuel and James McCracken in the very minor role of The Judge. Still, beginning with Anderson, many of these artists seem to be giving performances below the level of their best “golden age” efforts.

It may just have been a bit late in Anderson’s distinguished career for her to make her debut as Ulrica. She begins her famous scene in very tremulous voice, seeming uncertain and tentative in her vocal choices. As the scene progresses, she seems to gain confidence and power and a deeper sense of character in her singing; still, those that come to this broadcast expecting an astounding or revelatory Ulrica will likely be disappointed.

Milanov’s Amelia is similarly problematic. I expect that even her most fervent fans would agree that she seems to be in some distress in this broadcast. While there are many moments where her plush, velvety tone, especially in the middle voice, was abundantly in evidence, she seemed to struggle with many high notes. The end of the Act 2 duet “Teco io sto” is a most peculiar example of this, as Milanov fails to take the final high C but instead drops down.

Throughout the performance, she is lunging at high notes, frequently chopping them off early, and the result is screamed or squawked sounds that are very unpleasant to hear. It should be said that she sings a gorgeous “Morro, ma prima in grazia” (though it is met by tepid applause) and that her famous pianissimi are still ravishing. Still, this seems like a very “off day” from the soprano.

The pleasant surprise of this recording is the Riccardo of Peerce, a singer whose timbre has not always been to my liking. Here, his tenor, slightly grainy at first, fills with warmth and beauty throughout the performance. Peerce sings a suave and stylish Riccardo, comfortable throughout the range and with a real sense of character and personality.

Merrill’s glorious baritone makes a splendidly sung Renato, with all the power and ease and gleaming sound that the role requires. Still, he brings no particular sense of who his Renato is; I admired the tonal beauty but thought his sense of the drama was rather bland. His technique in “Eri tu”, for instance, was flawless; but one admired the singing without feeling the drama of the moment.

Peters is a charming, coltish Oscar sung with vivacity and charm.

This broadcast is remarkable for the quality of orchestral commitment, which makes Verdi’s music a powerful dramatic statement. The singing, while generally fine by today’s standards, is ultimately disappointing when one considers the slate of singers involved.

In contrast to this Ballo, the conducting is a major impediment to the success of the CD

of the February 22, 1964 Rigoletto, released in the same series. Fausto Cleva leads a plodding, excitement-free rendition of the score, lacking in propulsion and dampening the moments of high emotion with metronomic dullness.

The highs and lows of the music are flattened out to a middle-of-the-road runthrough lacking in powerful climaxes and moments of quiet serenity. The “standard cuts” are taken in the second scene and elsewhere; a pity, because I would love the chance to hear Richard Tucker sing the cabaletta “Possente amor.”

The extraordinary cast of singers do, for the most part, breathe considerable life into the proceedings. Peters is a superb Gilda, and manages, as Callas does in the role, to bring three different voices in the three acts. She is innocence itself in Act One, darker and wounded in Act Two, and has grown into a woman by Act Three. Her “Caro nome” is gorgeously sung and tastefully ornamented.

Tucker sings a fine, swaggering Duke with honeyed tone and a remarkable sweetness. One could, however, wish for more seductive passion in his performance; there is little of the seducer in his work and little palpable chemistry between the Duke and Gilda.

The supporting cast is golden and full of strengths. John Macurdy is a gutsy, dark-voiced Monterone; Bonaldo Giaiotti is a menacing and genuinely frightening Sparafucile; Mignon Dunn is one of the best Maddalenas I’ve heard—boisterous, lusty, full of humor and desire expressed with her fruity mezzo.

This brings us to the Rigoletto of Merrill, about whom I could repeat my comments about his Renato in the Ballo broadcast. He sings Rigoletto with absolute ease and surpassing beauty, but only the grieving father side of the jester is explored with any commitment. Merrill completely misses the inner bitterness and rage that Rigoletto clearly tells us that he feels.

When he sings “O rabbia!” in his aria “Pari siamo”, it sounds more like annoyance than rage. “Cortigiani” fails to ignite in the first section (as much due to Cleva than Merrill) but finishes with glorious tone and a touching sadness in the jester’s pleading for his daughter. And, alas, “Si, vendetta” sounds here like an empty threat, bearing no resemblance to a the cries of a man desperate for blood vengeance on his tormentor.

One can sit back and thoroughly admire Merrill’s ability to sing beautifully, but we wait in vain for him to imbue his music with the required passion.

This recording will delight those for whom opera is indeed “voice, voice, voice.” It is a pleasure to hear, and harks back to an era where sheer tonal beauty was paramount. But Rigoletto is not all pleasure; there are moments of horror and ugliness, Here, the drama is definitely not as important as the singing.