It delivers a thoughtful examination of the themes and symbols of this complex work, a detailed exploration of how the plot and dramatic arc of the opera prefigure the history of modern Germany and Bayreuth itself, and, most of all, a deeply moving, cathartic theatrical experience that serves as a testament to the continued possibility of redemption.

In this production, time really does become space. Location, chronology, and identity all move with a seamlessness that even a film director might struggle to replicate. The action begins almost immediately after the prelude starts when the curtains part to reveal the interior of Wahnfried, Wagner’s home in Bayreuth. Herzeleide, Parsifal’s mother, lies dying in bed. She begs her fearful son to approach her. He does so reluctantly and then goes off to play with his bow and arrow. While he is away she dies; a doctor and maid prepare the body. A curtain is drawn over the windows; it is identical to the stage curtain in the Festspielhaus.

Parsifal returns. The figure in the bed begins to writhe. His mother has changed into Kundry and she grabs the boy, smothering him in her embrace. He runs away towards the front of the stage and begins to surround himself with stone blocks. His fortress comes to resemble Klingsor’s tower. The curtains towards the rear of the stage part and the front of the set stretches and expands so that we are now in Wahnfried’s garden with the all-important bed center stage by the fountain and Wagner’s grave over the prompter’s box. Gurnemanz and the other knights of the Grail have wings like eagles, symbolic of both their divine mission and the fledgling German empire.

And this is just the first few minutes of the show. From there, Herheim manages to tell the story of Parsifal’s quest and to recapitulate the next 100 or so years of German history.. I would be hard-pressed to summarize the details of the staging in a reasonable space. Instead, let me choose a couple of highlights that give a flavor of the production. During the Transformation scene in Act I, Parsifal’s life plays out before him; his mother gives birth (in that bed, of course) and then Kundry steals away the baby. A platform rises out of the central fountain and the baby is brought there to be circumcised. At the moment of circumcision, Amfortas cries out in agony.

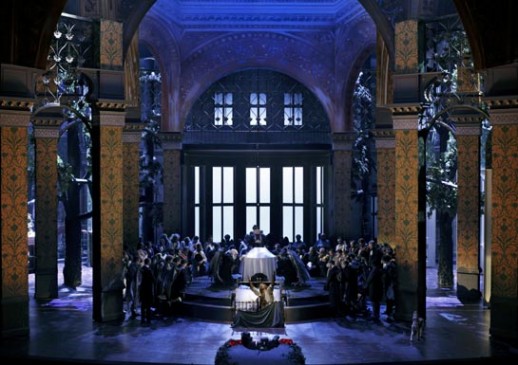

With these few deft strokes (as it were), we are confronted with both Kundry’s Jewishness and the symbolic nature of Amfortas’ wound. While this is happening, elaborate arches descend from the flies and the central portion of the set has become a replica of the set for the Grail Temple from the very first Bayreuth production of Parsifal.

Act II manages encompass the time period from World War I to the end of World War II. Klingsor, in fishnet stockings, holds sway over an army field hospital, his army a monstrous assemblage of dead and dying soldiers. The flower maidens begin as field nurses before they achieve efflorescence as Weimar Republic showgirls. Kundry becomes Lola Lala in The Blue Angel and delivers “Ich sah das Kind” with a seductiveness and conversational intimacy worthy of Marlene Dietrich herself.

For Kundry’s final attempt at seduction, she makes a quick unseen change to a white shift and flowing red wig thus becoming Amfortas himself in her efforts to make Parsifal see her as a victim. Such is the quality of the direction (or should I say audience misdirection) that her disappearance isn’t noticed until her surprisingly reappearance

The inevitable Nazis appear in the final few minutes until Parsifal destroys both them and Klingsor’s empire by plunging his spear into Wagner’s grave. Act III begins in the ruins of post-war Germany and with a little stage magic involving a few lights and a mirror shows the reopening of Bayreuth during the Good Friday Spell. The promised redemption does indeed come and we even get a dove at the very end in a beautiful image of hope for Germany.

Despite the visual and intellectual density of the production, the satisfaction of experiencing it does not its satisfactions are still primarily dramatic. The storytelling is always clear and wedded to both the music and the text. The different narratives embedded in the production bring additional insights, but unlike so many regie productions, a viewer doesn’t have to decrypt the production to enjoy it.

I do hope that the rumored plans to film this production come to fruition, as every Wagnerian should be able to see this production. It serves a welcome reminder that machines are not a substitute for stagecraft. The production itself is unlikely to ever travel given its extreme technical complexity. The stagehands got a well-deserved group bow during the curtain calls; they managed all the complex changes and precisely timed cues with remarkable precision and only a few thuds. In fact, they even managed the near impossible Klingsor starts to throw Spear/blackout/Parsifal holds spear aloft lighting cues perfectly.

Daniele Gatti led a supple performance that failed to have the expected impact, emotionally or sonically. He made little of the special Bayreuth acoustic for which this work was designed. The last time I heard Parsifal in Bayreuth, it felt as if the auditorium was the Grail Hall—the building vibrated and the unseen choir seemed to emanate from somewhere surrounding us rather than on stage. That did not happen and the orchestra had a dullish, gray sound.

Simon O’Neill was a very fine Parsifal, making much of his character’s initial innocence and naiveté and transition to full heroic maturity. His tone is somewhat nasal and wiry, but it had the requisite heft and impact. Detlef Roth as Amfortas , struggled vocally, nearly losing his voice in Act I. No indisposition was announced and he made it through Act III with fewer difficulties. While I would not want to pass judgment on his voice based on this performance, he certainly projected his character’s agonies with minimal reliance on the stock flailing.

Kwangchul Youn was a vocally imposing Gurnemanz. He was very enthusiastically received by the Bayreuth audience, but I found him somewhat bland in his characterization, particularly since this production presents him as Klingsor’s alter ego.

Reticence was not a problem for the Klingsor of Thomas Jesatko, who gave (you’ll forgive the expression) a ballsy performance. Not only did he work the fishnets and eyeliner; he dug deep into Klingsor’s dark nature without going over the top, even when the staging provided more than ample temptation. However, his acting was more imposing than his voice; I wasn’t sure how he would do in a different venue.

And finally, there was the protean Kundry of Susan Maclean. The character gets quite a workout in this staging; in fact, I lost track of her costume changes and sudden materializations. It required an extraordinary singing actress to pull this all off, which she did without a hint of showiness. Her attention to the text and musical line was most impressive. Other Kundries have had more voluptuous voices and sheer aural oomph, but I did not find her performance lacking. Of the many singers that were new to me at the festival, she was the one I was most eager to hear again.

This Parsifal served as a benchmark for what a “festival performance” should be—a presentation requiring the special combination of venue and performers as well as the rehearsal time and focus that are only possible in festival settings. It may have lacked in star power, but it dazzled with both heat and light.

Photos: Enrico Nawrath / Bayreuther Festspiele.