Necrophiliac pedophilia? Or a slow descent into madness? What really happened at Bly? After listening to Glyndebourne’s 2007 Production of Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, released in a live recording

under the festival’s own label, one is still left in the dark as to what really transpired at that English estate. Perhaps this is as the composer intended.

Britten’s opera, based on a novella by Henry James of the same title, sends us to the grounds of an aristocratic English estate. Miss Flora and Master Miles, children left to the care of their distant uncle, receive a new Governess (referred to in the accompanying booklet with a capital G). The Governess is instantly charmed by the Estate and the children: “Bly, I begin to love you,” she claims. She also becomes immediately friendly with the housekeeper, Mrs. Grose.

After an initial period of bliss, the Governess begins to see apparitions through windows in the tower and across the lake. Through her description, Mrs. Grose identifies them as Peter Quint, the former master’s valet, and Miss Jessel, the former governess – both dead. What have they come for, the Governess asks, and how can she protect the children from their influence?

It becomes clear that Miss Jessel seeks company in her misery, and asks Flora to join her on the other side of life. Quint, however, seeks a companion in Miles—a slave to his power:

I seek a friend . . .

Obedient to follow where I lead,

Slick as a juggler’s mate to catch my thought,

Proud, curious, agile, he shall feed

My mounting power.

Then to his bright subservience I’ll expound

The desperate passions of a haunted heart,

And in that hour

‘The ceremony of innocence is drowned’”

What he seeks in young miles is unclear; in life “Quint was free with everyone, with little Master Miles . . . . [h]ours they spent together.” Were Quint’s desires sexual in nature? Do they remain so, even in death? Resolved to save the children, the Governess asks Mrs. Grose to take Flora away, effectively breaking the girl of Miss Jessel’s influence. The Governess next attempts to confront Miles on his relationship with Quint. As Miles appears ready to reveal the truth to the Governess, Quint reappears one last time. After a struggle for Miles’s soul, the boy falls dead in the arms of the Governess.

The story’s subjectivity leaves a lasting impression in the mind of the listener. Was Quint really engaged with the boy in distasteful deeds? Or was the ghostly presence a figment of the Governess’ imagination? Does the Governess ask her concluding remarks of Quint or Miles, with the boy’s dead body lying in her arms: “what have we done between us?”

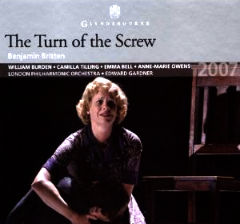

Glyndebourne’s excellent cast effectively conveys the slow descent into either madness or horror, leaving it to the listener to decide what really took place. Camilla Tilling’s Governess was delectable and she nimbly portrayed the young Governess’ hopes and fears for the children in her care. As always, William Burden shines in his ghostly allure as Peter Quint. Burden’s abilities for English language opera are astounding – perfect diction and beautiful phrasing are a hallmark of his performance.

Anne-Marie Owens is an appropriate Mrs. Grose, loving and loyal as British housekeepers are want to be. Owen’s diction is lacking in her higher register; without the libretto, it would be quite difficult to understand what she is singing. The children, played by Joanna Songi (Flora) and Christopher Sladdin (Miles) are astounding in creating the aura of evil surrounding them: do they cooperate with Miss Jessel and Quint, or are they simply under a spell? Lastly, Miss Jessel is played by Emma Bell who gives a very good performance of the depraved previous Governess’ desire for revenge.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra under Edward Gardner was quite good. Particularly, the bell choruses were stunning to hear, and the flute solos accompanying the ghosts’ soliloquies were spot-on.

Knowing this to be a chamber opera, I still found Britten’s composition left me wanting. It was not surprising to find out that Britten was late in finishing the work, and that he sought to prolong it: rather than adding more material (other than the short prologue) it appears Britten sought to prolong the opera with a slow pace. Moreover, it would have benefitted from a fuller orchestration that would help the listener “feel” the madness in the music, not just experience it through the performers. This, however, might take the opera out of Britten’s realm, to the chagrin of many.

Glyndebourne turns out beautiful packaging under their own label – a booklet that also serves as the CD cover. It might have been ideal to do a studio recording of this intimate piece, however, as the microphones in the live recording pick up stomping of the children and lose voices every few minutes. There was a whole passage from Mrs. Grose in the accompanying libretto that I was unable to hear on the CD. The aesthetics of the CD alone, however, make this recording a welcome addition to my bookshelf and Britten lovers may enjoy this fabulous cast in The Turn of the Screw.

Comments