A documentary about the heldentenor Max Lorenz would seem to be an ideal prism through which to examine the moral ambiguities and trade-offs of artistic life in the Third Reich. The preeminent Siegfried, Tristan and Tannhauser of the Nazi era was considered so essential to the success of Bayreuth that Winifred Wagner told Hitler that without him, she’d close the theater. The fact that Lorenz was also a homosexual who entered into a marriage of convenience with a Jewish woman who doubled as his manager makes his story all the more complex and fascinating.

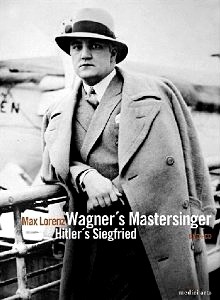

Wagner’s Mastersinger, Hitler’s Siegfried ($24.99, MediciArts) regrettably glosses over the most compelling elements of Lorenz’s life to deliver a somewhat predictable, sentimentalized account of an echt German singer’s career. Though the 54-minute film acknowledges the emotional hangups of a vulnerable nation in search of heroes and how Nazi politics co-opted art, one is left unsure at the end whether Lorenz was opportunistic, boldly defiant or just plain lucky.

Clearly, he was in the right place at the right time. The singer, born Max Sulzenfuss in Dusseldorf in 1901, possessed a hard-edged, ringing sound and a commanding stage presence that made him highly sought after even in his 20s. Emotionally insecure and prone to distorting the vocal line for expressive effect, he became highly dependent on director Heinz Tietjen, who would occasionally conceal himself in scenery like Siegfried’s forge during performances to help keep his charge from getting carried away. An invitation from Richard Strauss to sing in the 1928 premiere of his Ägyptische Helena in Dresden proved a turning point, earning Lorenz engagements at Berlin’s Staatsoper, the Metropolitan Opera and other leading houses.

Lorenz’s artistry is recalled in the film through interviews with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, tenors Rene Kollo and Waldermar Kmentt, the soprano Hilde Zadek and his biographer Walter Herrmann. The camera dwells for minutes at a time as these and other commentators mouth the words to arias and grow visibly wistful listening to excerpts from Götterdämmerung, Rienzi and Otello. Lorenz had natural energy, a way of pouncing on notes and an open-throated delivery that was unhindered by register breaks, they testify in German. “Today, you won’t find anyone who could hold a candle to him. No one. Hot air, that’s all,” Fischer-Dieskau says. With raves like that, it’s perhaps not surprising the film makes no mention of Lauritz Melchior, Lorenz’ great contemporary and arguably the better musician.

The film includes archival footage of Lorenz rehearsing the “Preislied” from Die Meistersinger at Bayreuth plus tantalizing old footage of Winifred Wagner recalling her confrontation with Hitler after Lorenz was found in flagrante with a young man at Bayreuth in 1937 and put on trial. When Hitler informed her that Lorenz could no longer appear at the Festspielhaus, Wagner said she replied “Bayreuth is impossible without Lorenz.” The Führer, so prominent restoring the house Wagner built, soon relented, and Lorenz sang on.

Lorenz’s connections with the Nazi hierarchy also saved his wife and mother-in-law after the SS burst in on the pair while he was away performing, in 1941. Lorenz’s wife had the phone number of Hermann Göring’s sister, who apparently helped intercede in the nick of time. Lorenz, on his return, was so furious he cancelled a performance as Tristan in Vienna that Hitler was to attend. Soon, he and his family won special dispensation from further crackdowns in the form of a personal letter from Göring.

Kmentt indicates in the film that Lorenz also interceded on behalf of Jewish friends and colleagues, but doesn’t provide details. The film briefly acknowledges that the family could have emigrated but decided to stay put, as Lorenz leveraged his celebrity. German artists were “idealists” and perhaps tone deaf to politics of the day, Lorenz’s colleagues say. “He could more or less do what he wanted,” Kmentt recalled.

After the war, Lorenz escaped the de-Nazification reviews reserved for many musicians who stayed in Hitler’s Germany and moved to Vienna, where he became an Austrian citizen. He eventually mentored a new generation of Wagnerian tenors, including James King and Jess Thomas. But the vocal selections excerrted from this part of Lorenz’s career show him to be somewhat erratic, reckless with note values and apt to overdramatize the contrasts in the music.

The package includes a bonus CD of Lorenz highlights from a previously unreleased 1938 performance of Siegfried in Buenos Aires, conducted by Erich Kleiber. Though all of Act 1 and most of Act 2 are preserved, the poor sound quality makes it difficult to come to any firm judgments. Like much else in this set, the material leaves one intrigued but ultimately no closer to Lorenz. The package should nonetheless keep ardent Wagnerites and vocal history buffs solidly entertained.

Comments