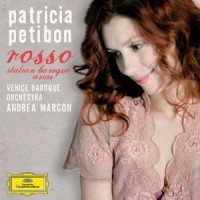

My grandfather warned me once: “Beware redheaded women. They’re both good and evil, depending on the second.” On Patricia Petibon’s new album

Rosso the soprano combines arrestingly beautiful singing and aggressively amorous characterizations with wildly dramatic artistic choices so easily and effectively, that she in a way lends an air of truth to the old superstition.

Petibon’s voice has always seemed destined for success in this repertoire, with a brilliant tone and facile command of period styles and ornamentations. She at times uses such a stunning, whispered straight tone, that she blends in eerily with the period violins doubling her part before easing slowly into her full, lustrous voice and continuing the phrase. It’s moments like this that have made her a star, and they are abundant on this album.

However, on Rosso Petibon dives headlong into what can only be described as a Kunstdiva mindset, at times throwing vocal beauty to the wind to achieve stunning dramatic effect. What ensues is a fresh, exciting and entertaining album of arias that are all too often ignored; considered simple or trite. Rosso includes singing that would at times fit more as Lulu than Cleopatra, but the dramatic thread that connects the two heroines becomes all the more apparent through Petibon’s revelatory interpretation.

Rosso offers a broad sampling of Baroque repertoire, alternating customary selections for an Italian Baroque record with relative rarities, including works by Nicola Porpora, Benedetto Marcello and Alessandro Scarlatti.

A particular delight from this underperformed repertoire is the opening aria, from Giulio Cesare in Egitto by Antonio Sartorio. Petibon highlights the aria with her most daring vocal choices of the album, including haughty laughter, scoops and slides into and out of notes, and luscious whispers, creating a Cleopatra of unmatched cunning and sexuality.

Another highlight of the album is from San Giovanni Battista by Alessandro Stradella, the 1675 setting of the story of St. John the Baptist which is far better known from Strauss’ Salome. Petibon portrays Salome as a genuinely affected, or brilliantly manipulative, young princess pleading for “poca mercè” after St. John’s pronouncements in her father’s court, eventually leading to his beheading. The aria is slow and touching, and Petibon’s phrases melt into the accompaniment with grace and guile.

The only major faults that struck me were the lack of a well executed trill, which in proper Baroque styling should be the highlight of any aria, and some less than desirable Italian diction. Most egregiously, the over-pronounced “r” in “piangerò” sullies what is otherwise a striking rendition of the famous aria from Gulio Cesare. That said, Rosso is still an artistic achievement worthy of purchase, repeated listening, and much admiration.

Comments