“The production by Mary Zimmerman is basically an eye-catching, imaginative winner, though the choreography needs a bit of revising. Renée Fleming wasn’t giving her all until the final scene but certain problems she has shown in the past were evident even so. Lawrence Brownlee is wonderful and damn adorable onstage, but Barry Banks is demi-god given the brevity of his role. Riccardo Frizza needs a double espresso.”

Sr. Maldè continues with more detail, including a spoiler or two:

Much of Rossini’s greatest music and most influential works that changed the course of 19th century opera were not comic operas. Each one of his opera seria masterpieces written for Naples established a new path that his successors followed. His 1817 Armida written for the Teatro San Carlo in Naples for the prima donna assoluta Isabella Colbran is the sole example of the “fantastico” genre – a work that blends fantasy and magic into the storyline.

This genre was not one that Rossini particularly appreciated – he suppressed the supernatural elements in his treatment of the Cenerentola libretto. So Armida with a libretto by Giovanni Schmidt taken from Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (which had been set by dozens of composers for over a century previously) looks simultaneously backward to the baroque and forward to romanticism.

The extensive use of ballet harks back to French baroque opera traditions. Of course, the protagonist is a major role for a prima donna in all versions and Rossini probably already was falling deeply in love with Colbran Isabella, the protagonist is both a vocal marathon and feast. Divas have been instrumental in bringing Armida back into circulation – notably Maria Callas in 1952 (one wishes Callas had sung more “seria” Rossini roles – notably Ermione). The most recent exponent is La Fleming, whose international career got an early boost from the part at the Pesaro Rossini Festival in 1993. Fleming’s star power at age 50 has brought the work to the Metropolitan Opera for the first time in its 127 year history.

So, enough preamble: how is the production and how was the “beautiful voice” (even judged in rehearsal conditions)? Well first of all this was very much a working rehearsal – the lighting was being adjusted constantly. There were mistakes in the orchestra – the French horn, for example, was not having a good afternoon. For the whole long first act, Renee did not sing full voice. In fact only in the dramatic final scene did we get the full Fleming effect.

Like “La Scoopenda” herself, director Zimmerman has come in for a lot of abuse on this site – some of it deserved, e.g., La sonnambula.

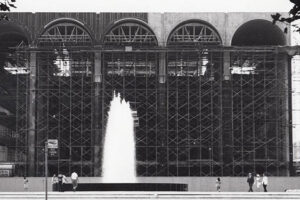

Her Armida production is much more of a success in the vein of her Lucia – in fact the element of fantasy and whimsy written into the music accommodates beautifully her more fanciful excesses. First of all, the production is visually beautiful: the imagery is elegant and appropriate to the opera. The sets and costumes by Richard Hudson view the medieval crusader setting through a double lens of surrealism and nineteenth century pictorial fantasy. There is a row of old-fashioned footlights downstage and a show curtain of a stormy sea. A classic semi-circular white wall studded with open doorways provides a versatile unit set for each act. Fantastical pieces and decorations are lowered from the flies in classic baroque theater tradition. The costumes are colorful and range from period-specific to pure fantasy.

During the overture Zimmerman introduces mime performers as allegorical figures representing love, vengeance and dance doubles for Rinaldo and Armida. The idea is actually very good – similar to the allegorical prologues in the Monteverdi operas and other baroque pieces – but the execution is shoddy. The movement for the mimes is amateurish in design, robbing them of otherworldly power and their physical interaction with the characters in the story confuses their function. Some of the movement for the chorus looks silly – from jogging crusaders to campily scampering demons in Act II.

On the other hand, the blocking for the principals is effective and intelligent. The choreography by Graciela Daniele similarly goes from classy to campy – elegant harem maidens clash with boogying devils in spandex (who look like refugees from Cats) who reappear for the divertissement in ballerina drag. Here, perhaps, the whimsical was taken too far. The good news is those things that can’t be changed – the sets and costumes – are stunning and successful. The goofy excesses of the staging and choreography can be toned down.

Riccardo Frizza‘s conducting, particularly in the ensemble driven Act I, lacked rhythmic drive and cumulative excitement. As for the singing, well this was a rehearsal so final judgments must be waived.

Come Monday night there will surely be a chorus of Renee bashers saying that her voice is gone, it has no core, she couldn’t be heard, she is over the hill. This may or may not be the case. For this rehearsal — she was clearly marking and saving — much of her ornamentation seemed to be pushing the tessitura upward into an upper register that didn’t always bloom freely. The silvery floaty beauty of the tone suggested a lorelei enchantress but slighted the darker more sinister, passionate colors Callas brought to the role. Of course, Fleming’s soft-grained tone never has had the tonally focused thrust of a Deutekom or Miricioiu for the more dramatic pages

In most of Fleming’s bel canto excursions (Lucrezia Borgia, Il Pirata) I have had issues with the fussy, rhythmically wayward quality of her coloratura – bel canto is based on classicism and Fleming’s phrasing is always playing outside of the bar lines. All of this holds true here. Her interpretation of the role is very charming but lacking in emotional core. The protagonist is a conflicted double personality: a seductress who believes she can control love for her own purposes, but who ironically becomes the pawn of her own seduction. The woman in love destroys the all-powerful enchantress, but that duality was not highlighted here.

As for the six tenors, two stood out: the afternoon very much belonged to Brownlee but, had Banks been cast in a larger role he might well have stolen the show from his American colleague. Brownlee has lost a good deal of weight and now looks absolutely adorable with his beautiful smile with dimples. He’s perhaps a little too much the male ingenue for a heroic crusader but definitely a heart stealer. The role of Rinaldo lacks an aria but is full of demanding and worthwhile music. Brownlee’s voice is a touch light and high-placed for this role written for Andrea Nozzari who combined the baritonal sound of a Verdian spinto tenor with the agility of a castrato. However the beauty of the tone and his mastery of expressive ornamentation commanded the stage every moment. Definitely a star-making turn.

John Osborn‘s ringing tenor and stalwartly handsome stage presence made for a fine Goffredo. José Manuel Zapata‘s darker baritonal colored sound sounded more suited to the envious and violent Gernando than it was for Almaviva, his Met debut role. His top notes were not easy or well-integrated into the voice and his big double aria was somewhat blunted by Frizza’s listless conducting. Yeghishe Manucharyan‘s dulcet tenor was wasted on the three line comprimario role of Eustazio; the Met might consider switching him with Kobie Van Rensburg who sounded out of sorts this afternoon as Ubaldo.

Banks’ gleaming tone and perfectly turned ornaments and trills made Carlo the focus of the third-act duet and trio. Peter Volpe and a spandex-clad Keith Miller (displaying a package that sent my soul to hell – at least I will have plenty of parterriani company there!) made sonorous bass sounds contributing necessary tonal contrast to all the high voices.

Rossini wrote a wonderful opera and it is wonderful to have a Rossini opera seria at the Metropolitan Opera. Let the Swan of Pesaro have the final word and ultimate praise.

Comments