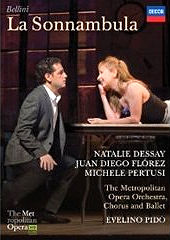

United into an angry mob, the Parterre community, for once, agreed: Mary Zimmerman’s deconstructionist rehearsal room-set production of Bellini’s opera was a disaster. No, not a disaster; it was a travesty. No, not a travesty; it was filth. Watching the newly released DVD of the production’s HD transmission, I’m not sure I agree. The production is not, in the end, successful. But it is not the miserable failure from beginning to end that reading this website in April 2009 would have lead you to believe.

Zimmerman’s concept, as we all know by now, was to take the decidedly slim plot of Sonnambula and set it in a rehearsal room in downtown Manhattan, where an opera company is putting on a traditional, Alpine-set production of the opera. The soprano and tenor singing “Amina” and “Elvino” are also named Amina and Elvino, and are engaged in a love affair that mirrors their characters’. In theory, such a production could work very well, but Zimmerman missteps early on and after the opera gets off to a solid start, the line between reality and rehearsal blurs too early and too often.

For the first twenty minutes of the opera, we know what’s going on. Lisa the stage manager is jealous that her ex-boyfriend, the tenor Elvino, is now involved with the soprano Amina. Great. That’s real. Amina and Elvino rehearse the contract-signing scene. Fantastic, that’s the opera-within-the-opera. Elvino, in a lovely touch, motivates the sublime love duet “Prendi, l’anel ti dono” by suddenly proposing to his girlfriend. Lovely, and very real. Then Count Rodolfo enters, and everything kind of grinds to a halt for the next two hours.

Who is this guy? Is he the singer playing “Rodolfo” in the opera? Is he, perhaps, the new head of the company? Is he just some random guy who wandered in off the streets? Zimmerman apparently intended him to be a former star with the company returning to the studio for a look around, but that isn’t evident in the least.

More questions get raised following this mysterious appearance. If Lisa is the stage-manager, who is singing “Lisa” in the opera? Why does Lisa offer Rodolfo a bed in the rehearsal studio; is that real or part of the show? Why do the chorus trash the place when they discover Amina there? Why, if this is 2009, does everyone react as if they’ve never heard of sleepwalking? We can rarely tell when we are in the reality the characters inhabit and when we are in the opera they are rehearsing. Nothing is clear.

It’s only in the final sleepwalking scene that Zimmerman achieves anything close to the theatrical magic anyone who saw her Tony-winning work on Metamorphoses knows she is capable of. When Amina makes her entrance walking on the snowy ledge outside the window, it’s breathtaking. When she sings the aria standing on a plank over the orchestra pit, it’s heart stopping. And then Zimmerman blows it again with an intentionally cheesy finale as the chorus and characters dance around in lederhosen.

Musically, things are a lot happier. Evelino Pidò does a credible job in the pit, and the chorus, under Donald Palumbo, sounds excellent. The cast is incredibly game, and generally successful. Jennifer Black, as Lisa, gives probably the most fleshed out portrayal of any of the singers and brings an attractive fruity tone to an ungrateful role. Jane Bunnell and Jeremy Gaylon (surely one of the most promising young singers now doing yeoman duty at the Met) do much with the little given to Teresa and Alesso, here apparently reconceived as Amina’s assistant and chorus master respectively. Michele Pertusi sings Rodolfo’s aria with finesse, but he’s got a thick, muscular bass and is rather stiff.

Juan Diego Flórez may give basically the same characterization he gives for all of his roles, but this performance finds him at the peak of his game. Once again he proves why he is widely considered the best bel canto tenor in the world with beautiful legato, clean coloratura and thrilling high notes. When he finishes his beautiful second act aria, a defining roar goes up from the Met audience, and after the cabaletta, the roaring returns at twice the force. There is no need to bandy words about: his Elvino is magnificent.

I hesitate to label Natalie Dessay’s Amina as such. Though she’s in better vocal condition than in the recent past, pitch issues are beginning to creep into Dessay’s upper registers; many of the high notes are now just shy of pitch. What’s more troubling here is that Dessay, usually a decisive and specific actress, never quite manages to create a clear character as Amina. Perhaps she was hampered by Zimmerman, perhaps by the libretto itself.

When she first enters, she is very much the diva in rehearsal, constantly on her cell phone. As she sings “Come par me sereno”, she tries on a rehearsal skirt, rejects a pair of shoes and accepts another, and (in what may be a jab at Angela Gheorghiu’s famous dust-up with Joe Volpe) rejects a series of wigs. It’s funny but it’s all a bit frantic, and the “diva” aspect of Amina’s personality is never referenced again; for the rest of the show she is very much the sweet-natured fiancée of the original libretto.

Dessay, in general, has trouble keeping still on stage. She is constantly walking, skipping, dancing and tossing off high around. It is only when Amina is asleep that she achieves a certain dramatic stillness that serves her well in the two sleepwalking scenes. “Ah non credea mirarti” is definitely her best work in the opera.

The major problem with this staging is that everyone involved, from the singers to the director to the general manager of the company, seemed to approach this opera from a viewpoint of “this opera’s plot is ridiculously lame, so we need to go wacky to entertain the audience.” In fact, Deborah Voigt, acting as the HD transmission “special guest host” basically says so in a short introduction to the opera. (The disk’s scanty special features consist of the HD intermission interviews.)

But La sonnambula is no dumber than any other plot of the bel canto era, and probably makes more sense than Puritani and Semiramide combined. It’s possible to do this opera straight and not look foolish. Zimmerman, to her immense credit, allegedly planned to do a more literal staging before Dessay used her pull with Gelb to get the idea nixed. That doesn’t absolve Zimmerman by any means, though; her execution, rather than the concept, is really where the production’s major faults lie.

Here’s the thing: Zimmerman is one of the most original voices in theater today. She is generally less sure of herself in opera, but unlike many I thoroughly enjoyed her Lucia di Lammermoor. Her concept for Sonnambula was fresh and intriguing, but turned out to be interesting but poorly thought-out. It could have worked. And that’s the saddest thing.

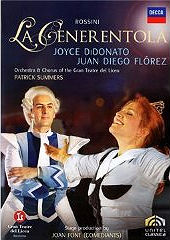

On the new DVD of La Cenerentola filmed at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, DiDonato’s enjoyment is visible in every frame of film and every note of the score. She clearly loves the part, the opera and the production, all of which she confirms in a bonus-feature interview. Her joy is infectious, making the experience of watching the DVD perhaps more fun than it should be. DiDonato’s Cenerentola is subdued rather than browbeaten.

That is not to say that she is lacking the necessary melancholy, far from it, but there is always a spark of defiance lurking just behind the willingness to obey. At the same time, she obviously yearns so strongly for the acceptance of her family and the love of a good man that when she finally gets it, her happiness is nearly overwhelming. “Nacqui all’affanno” is a joyous triumph, not just for Cenerentola but for the performer as well. DiDonato seems to revel in the aria’s challenges, and the final rondo explodes with confidence, gorgeous warmth and perfect trills. I could watch her sing forever.

She could not have a better Prince Charming than Flórez. It cannot be said of many singers that they can be relied upon to be astounding, but Flórez somehow manages it. I don’t think I’ve ever heard him give a bad performance, and this is no exception. In the interview that makes up the other half of the disk’s bonus features (technical aspects, by the way, are excellent across the board), Flórez calls Ramiro one of his favorite roles.

It is obvious from watching him why he enjoys it so much. His aria, “Si di ritrovarla”, is an exercise in eye-popping breath control, immaculate coloratura and spectacular high notes. Although he remains a tad stiff as an actor, his frustration at being ordered about by Dandini is very funny and the first duet between Cenerentola and the Prince is performed by both parties with gentle flirtation and delicate curiosity; clearly love at first sight.

It is mainly because DiDonato and Flórez are so good that the disk is so recommendable. Patrick Summers plows his way through the opera at breakneck speed, rarely pausing for a breath even in the recitative. The supporting cast is good, but not great, and the opera becomes a bit more of a star vehicle than perhaps it should. Bruno de Simone’s stuffy Don Magnifico is certainly expert, but he pecks at the notes a bit much. David Menéndez, a rising star in Spain, has something of the opposite problem: he is a solid, nimbly sung Dandini, lacking only the final touch of comic brio.

However, his interactions with Flórez, who appears continually frustrated at being ordered about by his servant, are funnier than anything else in the show. Simon Orfila’s Alidoro and the two step-sisters (Licea regulars Cristina Obergon and Itxaro Mentxaka) are all well sung but on the dull side.

Joan Font, of the Spanish performance group Comidants, has chosen to base his production on whimsy rather than wit and he is mostly successful. Joan Gullén’s sets are fairly minimal but his costumes can be described as Pop-art night at Versailles: brightly colored wigs, hoop skirts and frock coats abound. The most striking element of Font’s staging is the ever-present troop of Disneyesque rats, who appear to be in league with Alidoro and stage-manage much of the evening.

Played by cutely costumed dancers, it is the rats who comfort Cenerentola when she is at her lowest, who take to the ball, who cause the storm in Act two (hilariously, using old fashioned sound-effects machinery) and who, in the final moments of the opera, felicitate a stunning final tableaux, adding a note of ambiguity to one of opera’s most concrete happily-ever-afters.

As Cenerentola rejoices in her triumph, suddenly the prince and her family vanish and the rats plop a broom back in her hand. Has it all been a dream? But she still has the all-important bracelet on her arm, and DiDonato’s glowing smile says it all.

La Cenerentola has fared very well on DVD. Apart from this disk and the Met’s less starry but perhaps more evenly cast new outing, there’s Peter Hall’s fine staging from Glyndebourne, a wonderful video from Salzburg starring Ann Murray in the title role, a highly entertaining production starring Cecila Bartoli from Houston Grand Opera, and, of course, Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s peerless 1981 film starring the luminous Frederica von Stade. Liceu’s outing does not perhaps measure up to this last one, but I would absolutely recommend purchase as a second choice. DiDonato is simply not to be missed.

(Sonnambula photo: Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera)

Comments