Well, there’s enough leather to fill The Eagle ten times over, and there’s definitely fodder for intermission conversation: an adorable tweedy, puffy coat for Uldino; the pimped-out spiky bike helmet with the L.E.D. lights for Attila; all the L.E.D. lights in fact, like the ones that outline Ezio’s epaulettes; that insane blonde beehive wig with the single massive braid—worn, mais oui, with sparkly headband—that makes Violeta Urmana’s Odabella look half-Marge Simpson, half-Aubrey Beardsley Salome.

But, good, bad, or crazy, the clothes are just that: clothes.

Except for the occasional blazing flash of patent leather fringe catching the light, Miuccia Prada’s contributions to the Met’s first-ever production of Verdi’s Attila don’t register as costumes. They look like clothes being worn by people who happen to be on a stage. In mostly subtle fabrics and colors that run the gamut from dark brown to slightly-less-dark brown, they don’t register much at all.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if it wasn’t indicative of the production as a whole. According to director Pierre Audi, this production of Attila—which tells the story of history’s favorite Hun, the aftermath of his invasion of Italy, and his tragic love triangle with the vengeful woman who eventually murders him—is meant to reimagine that martial, bloody story “in a poetic, stylized way…[stressing] less the militaristic aspects in favour of the spiritual and poetic dimension of the drama.”

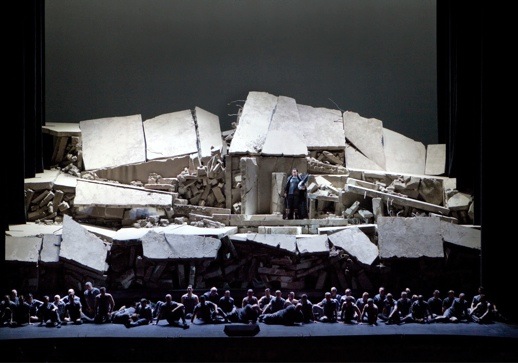

Leaving aside for a moment the dramatic problems with that approach to this material, what it means, as far as you could see on stage, is a lot of visual mushiness — a lot of dim lighting to go with the dark clothes. The chorus gets sequestered in rows beneath the main action; a few actors stand in for them, making solemn gestures. The soloists stand and sing, mostly far away from each other, bathed in spotlights.

Audi’s conception of the opera is Wagnerian in its utter seriousness and sobriety, and it feels at times like the production team is attempting a less extreme version of Robert Wilson’s Lohengrin. But Lohengrin was a work we knew well, and Wilson’s stripping-away of its calcified traditions—the swan, the silver armor—was exhilarating. And he created infinite tensions and dramas by focusing all of the action through movement of the slowest and subtlest kind. This Attila, on the other hand, lacks tension of any kind. In the course of removing anything that isn’t correct and proper, Audi and his collaborators inadvertently cleansed the opera of almost all of its infectious energy.

At least the energy was undimmed in the pit. The score is full of raging cabalettas and impassioned choruses, and belated Met debutant Riccardo Muti was sensitive to all the hair-trigger turns of emotion. But Muti couldn’t coax riveting performances from a cast of accomplished but uninspired singers. Violeta Urmana fared best: Odabella is a more congenial role for her than Aida was earlier this season, and she made some lovely sounds, particularly in her first-act aria, “Oh! nel fuggente nuvolo.” Ramon Vargas was ardent as Foresto, but he was uncomfortable at the top of his range.

Most problematic was Ildar Abdrazakov, who has a suave, small voice but lacks the charisma, vocal and dramatic, to navigate the title character’s alternately repellant and sympathetic actions and sell Audi’s version of the opera as Attila’s Greek tragedy. Abdrazakov didn’t dominate, as he must; he just faded into the background. There couldn’t have been a greater contrast than with Samuel Ramey, a great Attila of old, who was on hand for the short part of the bishop Leone. You could have driven a Mack truck through his vibrato, but you never forgot he was onstage.

All the singers lacked firm senses of their characters, despite their director’s ostensible focus on the “personal” side of the opera. But perhaps the production’s deemphasizing of the “militaristic aspects” of the plot makes a full depiction of the personal impossible. After all, the opera is entirely about the ways in which character emerges from military conflict, the ways in which societies defined by endless warmaking both can and cannot come to terms with civilization.

Individual personalities emerge from the context of the army, the crowd — that is why it is so strange and counterproductive that Audi banishes the chorus. We never get a good sense of Attila’s tremendous power, both scary and seductive, because we never see him interact with his army. And without a clear idea of that power, the opera, another step on the road to Verdi’s masterpieces and their intricate interweaving of the personal and the political, just doesn’t work.

The physical production, by Prada and renowned architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, is the apotheosis of the Met’s current ethos, which is all about flashing designer labels that have no relevance, in the end, to the realization of meaningful nights at the opera: Prada clothes, Herzog and de Meuron buildings, direction by genius-grant recipient Mary Zimmerman, and so forth. Everyone in this Attila looks suspiciously like Scarpia in Luc Bondy’s Tosca, and the battlefield set, all craggy postapocalyptic rubble, looks like a steroidal version of Act 3 of Richard Eyre’s Carmen. Attila has the same No-Time, No-Place, Kinda-Contemporary, Kinda-19th-Century aesthetic as many of the company’s recent productions.

Aggressively depoliticized and proudly modest about their ideological intentions, the goal of these productions is to rigorously avoid Regie cliches like, say, moving Attila to Iraq. But Audi’s production makes you long for those strident old gestures, which at least have the virtue of being about an opera’s insides rather than its outsides. (Attila in Iraq, or wherever, would at least give you a sense that the stakes of armed conflict have to do with more than the cut of the uniforms.) But the director seems entirely uninterested in the opera’s possible stakes, which might interfere with the “poetic, stylized” lethargy. And with Ms. Prada’s costumes.

Audi seemingly had impulses other than the ones he chose to stage, though. He might be talking about an opera entirely different than the one he directed when he writes about Attila’s second-act banquet in his program note, “We discover a world in chaos and anarchy, dangerously breeding nationalism and religious fervour in its quest for freedom from the invaders.” Now that’s a production I want to see. Where is it?

[All photos: Ken Howard, Metropolitan Opera.]