A new CD set of Der Ring des Nibelungen, recorded live at the Bayreuth Festival in 2008, is slim on superstar casting, but basks in the reflected glory of conductor Christian Thielemann, a controversial artist with a passionate following. So how does the music measure up?

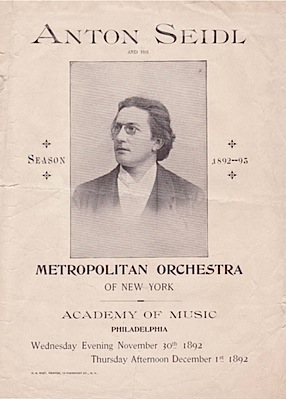

Conductor worship reflects the musical utopianism that has long been intertwined with the Festival. Joseph Horowitz’s book Wagner Nights: An American History describes the cult surrounding Wagner disciple Anton Seidl (1850-1898), who worked alongside Wagner at the first Bayreuth season and led the first performances of the Ring at the Metropolitan Opera. He was the focus of an unprecedented fascination among the ladies of New York’s elite social clubs, who wore embroidered “S” insignias on their blouses to show their devotion.

Seidl was divisive. Accused by some critics of pompous grandiosity, to others he was simply “perfect,” the authentic carrier of the Wagner flame. The public, reported Henry Krehbiel once in the New York Tribune, “used all the opportunities offered it to applaud the musician with all the enthusiasm that an opera audience can arouse.”

But Seidl was not a god but an apostle – a secondary figure in the cult of Wagner, which idealized the composer’s modernist musical and theatrical vision on one hand, and a longing for a lost Romanticism on the other. It is this curious mixture of Utopianism and sentimental longing that has always defined the argument over how Wagner should be performed.

German conductor Christian Thielemann has engendered a similar cult worship, and even more controversy. In the early 1990s, while still a house conductor at Düsseldorf, he was making his first appearances with major opera houses, including his New York debut at the Met in 1993 with Der Rosenkavalier. Appointed Music Director of Berlin’s Deutsche Oper in 1997, he gave up the position in 2004 in a bitter fight with Berlin’s city authorities over funding and autonomy.

Somewhere in this wrangling for control of Berlin’s opera houses, Thielemann was accused of making a private anti-Semitic comment about the Staatsoper’s Generalmusikdirektor Daniel Barenboim. He denied it, but the bitter taste has followed him. According to some of his detractors, Thielemann is not just a pompous reactionary musician, but even a catalyst for certain fans’ latent Nazism.

I observed a considerable Thielemann cult in Vienna when he conducted Parsifal there in 2005. Crowds would erupt in shouts and applause upon his entering the pit. At the time, I found his Parsifal strange and forced, with sluggish tempos that were inhospitable to the singers. Keeping an open mind, I came to appreciate his recording of Schoenberg’s Pelleas und Melisande (with the orchestra of Deutsche Oper Berlin). Rapturous, glowing sound pervades, but also a studious and transparent handling of Schoenberg’s orchestral layers. I even found myself using superlatives – could there be a better reading of this piece?

Thielemann is the boldest name featured on a new recording of Der Ring des Nibelungen, available this month from Arte Nova (14 CDs), which was taped live in 2008 at the Bayreuth Festival. The booklets accompanying the package, besides complete libretti, include a short essay titled Auf dem Siegestreppchen (On the Victor’s Podium) by Christian Wildhagen, which overlooks no opportunity to adorn Thielemann with laurels. He places the conductor’s “Wagnerian miracles” rightfully in the “Valhalla of Wagnerian performances” at Bayreuth. What do such miracles sound like, then, on disc?

Conductor Christian Thielemann making "miracles"

We are not living in a golden age of Wagnerian singing. While there are many excellent basses and baritones singing Wagner today, there is no glut of dramatic sopranos or heldentenors. Bayreuth recordings of previous decades could pass muster with mediocre orchestral playing simply because it had, say, Astrid Varnay as Brünnhilde, but this set succeeds instead – and it mostly does succeed – because of Thielemann’s dramatic, unifying approach to the mammoth work’s interlocking elements.

The orchestra begins Das Rheingold with a placid, meditative E-flat arpeggio, pristine in pitch, seamless in its passage between strings, horns and woodwinds. All the entrances, crescendos, and curves meld into an impressive swell of orchestral sound.

The Rhinemaidens scene is sung with sweetness and ease, though some forced high notes from Woglinde sour the mood. Andrew Shore is a slightly ragged Alberich, but the role is not prized for lyricism, and his characterization is otherwise vibrant and detailed. Christa Mayer, as Erda, displays solid musicianship, but the sound disappoints on disc. Her warning to Wotan should be like a beam of light, wise and ethereal, but Mayer’s sound, thin and hollow, is marred by a nervous quiver.

Vocally, Die Walküre is a step up, largely because of the excellent young Dutch soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek as Sieglinde and Kwangchul Youn as a lyrical, sensitive Hunding. Westbroek’s voice is already mature and wise, large enough to suggest the tired, burdened wife. She uses an inflected mezza voce to whisper to the sleeping Siegmund, then shines with the unburdened radiance of a near-goddess with her expansive lines “O fünd ich Ihn heut’ und hier!”

Albert Dohmen has the power and articulation to be a standard-bearer in the role of Wotan. Dark but not villainous, booming but never shouted, his voice also has a pathos and frailty that rounds out the tragic god’s sound-portrait. And as the Wanderer of Siegfried, his voice is solid throughout his range with particularly impressive lower notes that seem to amplify endlessly according to the demands of the phrase.

The detailed and thoughtful Act One shows particularly nice work from the strings. The violins play disciplined graded dynamics throughout, with lyrical and curvy melodies that also do not lack for rhythm, vitality or incisive sforzandi. The sound varies from gauzy and mellow, to the more sensual metallic, piercing hue recognizable from other Bayreuth recordings.

Thielemann imbues the orchestral playing with intensity and urgency later in the opera, when Brünnhilde resolves to assist Siegmund against her father’s wishes. Both orchestra and Linda Watson (Brünnhilde), brimming with paranoid frenzy, paint a vivid picture in the “theater of the mind.” Thielemann accompanies singers carefully, then in moments of action, he drives the music with exhilarating fire.

Stephen Gould grows into the Siegfried of the third opera, the voice eventually opening up to show more resonance and ping. His variable Siegfried yields perplexing results: while he surmounts the ferocious challenges of tessitura and sheer length with considerable facility, the sound is muted, and the top notes are often pinched. Throughout “Nothung! Nothung! Neidliches Schwert!” he struggles to be heard through the orchestral textures. Against Fafner the Dragon, sung by Hans-Peter König, Gould stands up better. Summoning a golden chest voice, he etches a mental picture of a true Aryan bully, spouting insults and spoiling for a fight.

Early in Götterdämmerung, Gould’s Siegfried takes on a lighter quality, thin and not quite heroic. Then in the Oath scene with Hagen, in Act Two, he is once more more piercing and elastic. However, he barely manages the high C of his “Hoihe!” to Hagen in Act Three of Götterdämmerung, cracking a bit on the way down.

As Mime, Gerhard Siegel is committed and exciting. He sings a full tilt performance, holding long notes tenaciously, and conjuring a Mime who is both evil and pathetically needy. In fact, he almost outshines the Siegfried, singing at first with greater passion and a more ringing tone than the hero.

Edith Haller’s birdlike Gutrune makes small moments such as “Wilkommen, Gast, in Gibich’s haus” glimmering and inviting. Though lacking a powerful voice, she nevertheless has the incisiveness for an arresting “Sie haben Siegfried erschlagen!” lending that scene, bringing a touch in intrigue to this unglamorous role. Hans-Peter König, as Hagen, and Ralf Lukas, as Gunther, are well matched as the half-brothers. König never shouts, as many Hagens do, singing with a dark but pliant, articulate bass.

Valkyries in Tankred Dorst's 2006 production of Der Ring des Nibelungen

Watson’s performance as Brünnhilde eventually reminds us what big shoes she’s trying to fill. Managing to sing with attractive coloration at first in Siegfried, she tires quickly, and her angular leaps and final high C (“Lachender Tod!”) are forced and unfocused. Early in Götterdämmerung she floats some lovely high notes, but by the end of her first duet with Siegfried, they squish and strain.

Toward the end of the Götterdämmerung, Watson seems to pace herself and hold her ground through the final act. But there is an impression of her darkening the sound to make it appear bigger than it is, distorting its focus. She is even swallowed by the orchestra in a few places – shocking on a recording, and in a house famed for its orchestral and vocal balance.

In her final monologue, the declamatory “Trog Keiner wie Er!” is loud enough, but lacking in steeliness to match the orchestra’s blasts of sound. Through the rest of the final scene, though she copes admirably with the challenges, she scoops into notes, beginning the first note of almost every phrase from below the pitch.

The long orchestral tableaux in Götterdämmerung have plenty of fire, but their primary appeal seems to be the richness of the orchestra’s lower register – brass and lower strings throb and burn throughout this Ring with a truly unique Bayreuth sonority, said to be as much a feature of that theater’s acoustics as the orchestra’s sound. If success in the Ring consisted only of eliciting the most resonant, rich sound, this recording would be among the best.

In Siegfried’s Death, Thielemann does not extend the fourth beats like some conductors, a traditional affectation that has become nearly compulsory. He does however insert a tiny crescendo on those beats, without disturbing the tempo – an tasteful and unobtrusive retouching. Horn calls in the Rhine Journey are accurate in pitch, but elsewhere the orchestra sounds imprecise and somewhat tired, especially in the cacophonous final bars following Brünnhilde’s monologue.

Wagner completists will welcome the first commercially produced Ring from that Bayreuth Festival in 17 years. This set is important, at the very least, as a document of the company’s current work. More skeptical Wagner fans will need a good reason to add yet another Ring to their shelves. Lengthy applause, including some curtain calls, remains appended to the ends of these live recordings, which some may find distracting at home.

Far from being a divisive figure, Thielemann here is a unifying force on the podium. Worth hearing? Sure. Though it lacks “perfection” in casting, orchestral playing, or sound quality, it has enough success in each to equal a satisfying whole. But Cult God or no, Thielemann can’t carry the entire venture, and Bayreuth’s previous Ring recordings cast a very long shadow. Lacking truly great singers in the principal roles and an orchestra capable of both precision and beautiful sound, this Ring is destined to remain a dwarf among giants.

Comments