The last day of December a parcel arrived in the mail containing an absolute delight

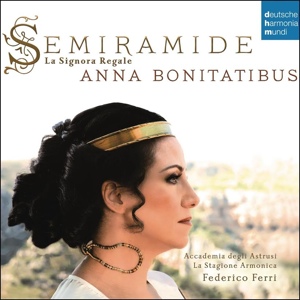

: “Semiramide—La Signora Regale.” One of best vocal recordings of 2014, this sumptuous 2-CD set on Deutsche Harmonia Mundi features the marvelous Italian mezzo-soprano Anna Bonitatibus and includes 90 minutes of rarely-heard music written for the legendary Babylonian queen.

In addition to striking reproductions of paintings and sculptures of Semiramide, the impressive 132-page, full-color booklet accompanying the set provides several fascinating essays (in four languages!) differentiating the important historical figure of the Assyrian queen Sammuramat who lived from 850 BC to 785 BC from the infamous virago of legend who turns up in everything from Dante’s Inferno to Voltaire’s 1748 play Semiramis to a 1950s Hollywood B-movie (or is it C?) embodied by Rhonda Fleming.

Lively, brief da capo arias by Caldara and Porpora set to earlier libretti from the 1720s illustrate the high baroque, while Jommelli’s dramatic accompagnato and aria from 1741

One feels a seismic shift at the beginning of the second CD with a sturm und drang-influenced overture to 1790’s La Vendetta di Nino by Bianchi. “Figlio diletto” from Borghi’s La morte di Semiramide ossia La vendetta di Nino which premiered the next year anticipates the cavatina-cabaletta structure as the queen struggles to comprehend how her beloved Arsace could, in reality, be her long-lost son moving from anguish in the initial slow section to fear in the spirited allegro conclusion.

A long excerpt from Nasolini’s 1792 opera could easily be mistaken for a lost scena from an early Rossini opera. For the first time, the chorus is prominently featured as the queen bubbles with elaborately jubilant coloratura celebrating her (doomed) love for Arsace.

We finally arrive in the 19th century with a charming canzonetta with chorus and harp obbligato from Meyerbeer’s Semiramide (the only excerpt previously recorded), followed by the world premiere of a reconstruction by Philip Gossett of an early version of Rossini’s “Bel raggio” which omits the traditional cabaletta “Dolce pensiero.” Accompanied only by wind instruments, a simple prayer by Manuel Garcia (famed teacher and brother of Maria Malibran and Pauline Viardot) concludes the chronological program, but “Fuggi dagl’occhi miei” from a Handel-Vinci pasticcio (sounding neither like Handel or Vinci) turns up as a “bonus” at the end of CD2.

Unsurprisingly, Bonitatibus was passionately involved with this ambitious project: she not only originated the concept and collaborated on the musicological research; she also wrote several of the CD’s extensive program notes and composed her own ornaments and cadenzas. If this all weren’t enough, she sings splendidly in the 12 demanding arias she programmed. Hers is a wide-ranging, idiosyncratic mezzo soprano, dark and smoky and always used with an urgent intensity that makes it instantly memorable. There can be a pronounced vibrato which I could imagine might put off some listeners but instead it lends her commanding singing a touch of appealing vulnerability.

One never hears just a series of notes—they are always linked with an unerring legato. Her impressive command of florid singing is most telling in that it rarely sounds like showing off—the melismatic bursts in an exciting bravura piece like “Il pastor se torna aprile” first serve Traetta and Metastasio’s grand similes for Semiramide’s hope that she will regain love with Scitalce.

Although I was initially unfamiliar with both the period orchestra—Accademia degli Astrusi—and chorus—La Stagione Armonica–featured on this recording, both perform suavely under the direction of conductor Federico Ferri. The orchestra in particular does well in idiomatic readings of the widely varied arias and instrumental pieces included.

That Bonitatibus has possibly remained unfamiliar to American audiences is not surprising. She has so far only appeared twice in the US—both times in northeastern Ohio! At the invitation of Franz Welser-Möst she performed Dorabella in a semi-staging of Così fan tutte in 2010 and then Rossini’s Stabat Mater a year later, both with the Cleveland Orchestra. Otherwise one would have come to know her through her other recordings and DVDs.

Her repertoire is not the usual Italian mezzo fare—no Azucena or Princess de Bouillon for her—she focuses primarily on operas from Monteverdi to Rossini. My memorable first exposure to Bonitatibus was her superlative Ulisse on Alan Curtis’s 2002 recording of Handel’s Deidamia opposite a dazzling Simone Kermes caught here before her off-putting self-indulgence took over.

Important aspects of Bonitatibus’s art can be viewed on excellent DVDs of several 17th century operas including Cavalli’s La Didone (though I find that opera very dull), and, although I don’t enjoy David Alden’s production, her Giunone is featured

in a marvelous cast in that composer’s Parisian opera Ercole Amante. As an imperial Ottavia in L’Incoronazione di Poppea she steals the show

from Danielle de Niese’s petulant Poppea and Philippe Jaroussky’s screamy Nerone.

US audiences for now must content themselves with these and the sterling, essential “Semiramide-La Signora Regale” while hoping that some American opera company or orchestra soon engages the regal Italian mezzo; however, next month lucky audiences in Lausanne will get to experience Bonitatibus’s first-ever Tancredi opposite Jessica Pratt while her spicy Isabella will enliven Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s venerable version of L’Italiana in Algeri at the Vienna Staatsoper opposite Javier Camarena and Ildar Abdrazakov in April.

Comments