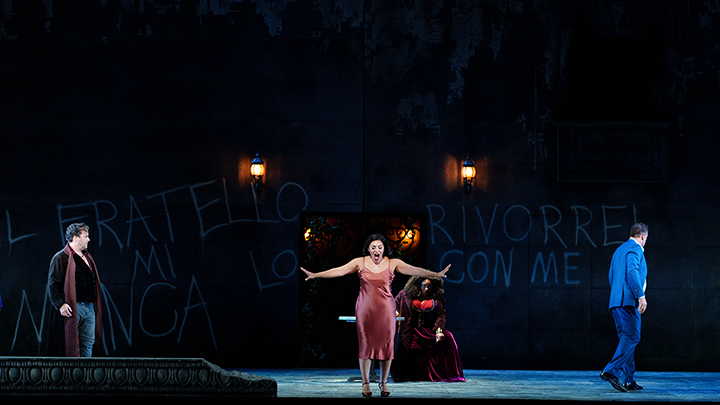

Set against the backdrop of the Basque rebellion in Spain, Stephen Wadsworth’s staging painted a stark divide between a white-collar militia and an oppressed, armed ethnic group—an allusion to modern-day social tensions. The tension between these groups underscored the broader societal divide, while murals by Houston-grown artist Floyd Mendoza reinforced this conflict, emphasizing the opera’s ongoing relevance.

Ailyn Pérez made an admirable role debut as Leonora, showcasing both technical precision and emotional depth. Her portrayal highlighted Leonora’s evolving passions, with each aria offering a distinct emotional journey. In “Di tale amor” (Act II), Pérez effortlessly floated through high notes, sending her overwhelming love for Manrico soaring heavenward. In contrast, during “D’Amor sull’ali rosee” (Act IV), each note seemed to escape like a trembling sigh, filled with despair and an overwhelming love that felt as if it were breaking with every breath.

Michael Spyres was flawless as Manrico, fully displaying his prowess as a baritenor. He balanced warmth and heroism, embracing Manrico’s contradictions. In “Ah! si ben mio” (Act III), Spyres sang with tender conviction, while in “Di quella pira,” his slightly fuller tone enhanced Manrico’s resolute determination. His final high C in “Di quella pira” was stable and impressively sustained, a clear testament to his technical mastery.

Meanwhile, Lucas Meachem delivered a compelling Count di Luna, playing him not as a villain but as a man consumed by obsession. In “Il balen del suo sorriso” (Act II), Meachem stood motionless at center stage, hands in his pockets, delivering the aria with calm restraint. Yet, through vocal nuance alone, he conveyed the depth of Di Luna’s desire and spiraling madness, making for a striking contrast against the more kinetic performances around him. Meachem delivered the most fully realized performance of the evening, bringing a deep understanding and emotional complexity to his character.

Raehann Bryce-Davis brought intensity as Azucena, though her initial numbers, “Stride la vampa” and “Condotta ell’era in ceppi” in Act II, felt less polished, possibly due to her not yet fully warmed up. Despite this, Bryce-Davis made it clear that her portrayal of Azucena was rich with emotional range—vengeance, love, and madness—all vividly displayed through her impressive vocal palette. By the time she joined Spyres for their duet “Non son tuo figlio,” Bryce-Davis had found her stride, pulling the audience fully into Azucena’s tortured world. In Azucena’s final lines—“He was your brother… You are avenged, mother!”—vengeance, guilt, despair, and madness exploded in a powerful mix of spoken and sung tones, leaving the audience enveloped in raw emotion.

Morris Robinson as Ferrando added gravitas with his rich, resonant voice, vividly recounting Azucena’s backstory. And despite the small role of Ruiz, Demetrious Sampson, Jr. made a strong impression with his powerful voice, showing he’s ready for larger roles in the future.

Maestro Patrick Summers’s conducting was finely tuned, especially during Pérez’s florid arias, where he carefully slowed the tempo to allow her embellishments to shine. Under his baton, the HGO orchestra delivered crisp, refined playing, bringing out the drama without overpowering the singers.

While the cast brought their characters to life with nuance, Wadsworth’s new production—one of the rare modern interpretations of Il Trovatore—was hit and miss. The opera’s famously convoluted plot, which overlaps past trauma with present-day drama, is challenging for any audience. To clarify this, the production split the stage in Act I, with Fernando recounting the story on one side and actors silently reenacting events on the other. Though it may have aided some in understanding, the mimed action often drew attention away from the singers’ emotive performances. Robinson’s commanding presence and vocal strength likely would have been sufficient without the silent actors.

Azucena, though central to the story, often gets overshadowed by the Manrico-Leonora dynamic. In this production, Wadsworth sought to refocus the narrative around Azucena, but the staging didn’t always cooperate. In the first act, Azucena sits at a table throughout, seemingly lost in grief over her mother’s death, accompanied by silent action.

When Act II begins, the space where she sat transforms into a cocktail bar filled with Romani people from the Basque region. While the attempt to ground Azucena in the opera’s emotional core was evident, having her enter the second act and immediately sing her pivotal arias after being seated for so long seemed a bit much. However, Bryce-Davis’s later performance fully justified the focus on her character, especially by the opera’s climax.

The modern Basque setting could have made the opera more accessible, aligning the story’s political context with contemporary events. However, the reworking of the famous “Anvil Chorus” missed the mark. Rather than blacksmiths hammering anvils, we saw fashionable characters walking a runway in a cocktail bar, drinking and tapping glasses in place of hammer blows. While clever from an auditory perspective, this staging erased the labor theme entirely and left the audience wondering: How does this production define the work and struggles of today’s oppressed groups? More exploration was needed to flesh out this concept.

HGO’s Il Trovatore is sure to divide opinions, but it undeniably offers a new take on Verdi’s beloved work—one that provokes conversation and debate. The remaining performances on October 26, 29, and November 3 promise more opportunities to experience this reimagined classic.

Photos: Michael Bishop

Comments