Many opera directors have resorted to gimmicky live camera feeds projected on stage. Krzysztof Warlikowski’s new production of Gyorgi Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre, reviewed earlier this week by Emma Hoffman, at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich uses the trope early on: the two lovers Amanda and Amando holding selfie sticks while admiring each other. In the final moments of the opera, the pair comes back after having survived the apocalypse by hiding in a grave, now singing “for life grants most to those who give and who gives love shall loving live.” The camera feed returns. This time, however, astronaut-like figures film the contents of deceased characters’ suitcases—luggage which they carried in during the opening scene while seeking refuge from an unknown peril.

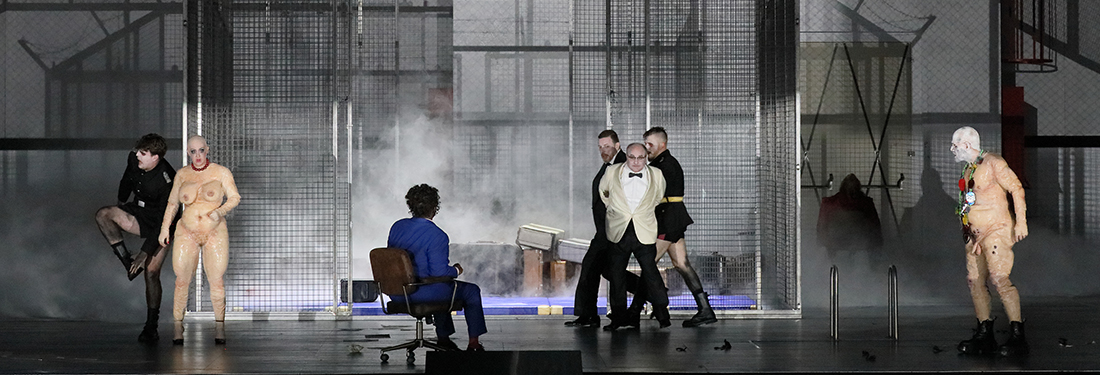

While these silent explorers could be uncovering an extraterrestrial massacre, the figures also harken to Romeo Castellucci’s 2022 Resurrection, a harrowing depiction of UN officials digging up a mass grave set to Mahler’s 2nd symphony. The stacks of old suitcases and barbed-wire fences evoke images of detention camps (an immigration facility or even a concentration camp), as does the decision to have the cast frequently sing from behind a front-stage metal fence. The camera operator opens a case to discover the score of Ligeti’s work and his portrait, as well as other black-and-white photos of families. Can the opera thus be understood as the composer’s own grappling with trauma, death, and memory of a past life?

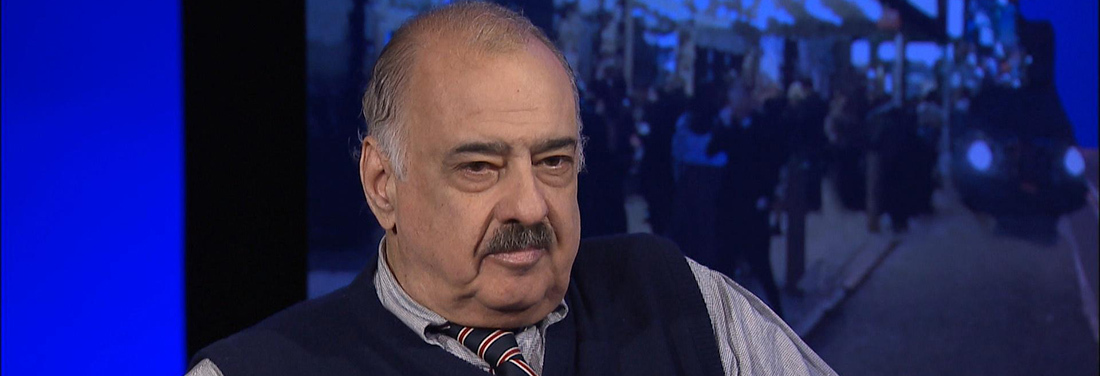

A Holocaust survivor and political refugee from Communist Hungary, Ligeti’s life was full of tragedy and upheaval. Musicologist Florian Scheding has however warned not to reduce Ligeti’s works like Le Grand Macabre or Requiem as simply reflections on the Shoah. Indeed, much of Ligeti scholarship has avoided discussing his experiences during the Holocaust and several reviews of the new Munich production have largely neglected mentioning Warlikowski’s decision to reference the composer’s biography. Scheding argues in his article “Where Is the Holocaust in All This? György Ligeti and the Dialectics of Life and Work” that trying to find Holocaust references in music “is not only tantamount to lugubrious voyeurism; it also poses an ethical dilemma.” What, then, is Warlikowski trying to do with Ligeti’s music? Through subtle imagery, the Polish director suggests that Ligeti similarly uses his music to reflect on history, political extremism, and his own faith and relationship with the past.

Le Grand Macabre, adapted from Michel de Ghelderode’s 1934 play La Balade du Grand Macabre, depicts the Apocalypse: the prince of death himself, called Nekrotzar, arrives to pass judgment on the fictional, hedonistic Brueghelland. Yet he is thwarted by the professional “wine taster” Piet, the aptly named court astronomer Astradamors, and Prince Go-go. The trio convince Nekrotzar to get drunk and pass out. Though they initially believe that they have been killed by a fiery comet, Piet, Astradamors, and Prince Go-go realize that since they are thirsty they must be still alive, thereby defeating Nekrotzar.

Le Grand Macabre was Ligeti’s only completed opera; his “Alice in Wonderland” project remained unfinished when he died in 2006. In the 1970s, he had written two short absurdist works for voices and chamber ensemble, Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures, and sought to provoke audiences further with a larger operatic project. By the 1970s, Ligeti sought to write a radical avant-garde “anti-opera” inspired by Mauricio Kagel’s provocative theater works, though he soon began to change his compositional style and the work turned into an “anti-anti-opera.” While still very much indebted to absurdist theater, the work nevertheless has a clear plot and musical structure.

In the late in 1960s and early 70s, Ligeti was part of a group composers who sought to distinguish themselves from the dogmatic avant-garde of the Darmstadt School and began to draw from music history through direct, often ironic quotations. Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia (1968) and Alfred Schnittke’s Symphony No.1 (1969) stand out in this category, though in terms of operatic works, Ligeti was almost certainly influenced by Bruno Maderna’s 1973 Satyricon and its use of allusions to Tchaikovsky and Wagner. Le Grand Macabre, completed in 1977, was rooted in numerous musical traditions through its use of collage and parodies not only from famous repertoire, but also from medieval chants, African polyrhythms, American jazz, and Eastern European folk music. Yet these references are often distorted and obscured — quotations are layered on top of each other in a style reminiscent of Charles Ives’s work. For example, the opening car-horn prelude parodies Monteverdi’s Orfeo and the passacaglia depicting the arrival of Nekrotzar’s retinue blends a distorted version of Joplin’s “The Entertainer” with Beethoven’s Eroica symphony.

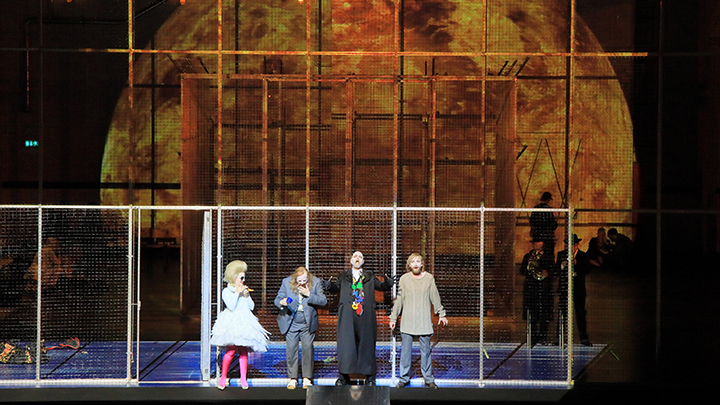

Yet the opera is not however a purely satirical work. It is also set within a mix of real-world historical allusions and fantasy. Ligeti revised the work in 1996, condensing it into four scenes without an intermission, extending the final passacaglia, and removing much of the spoken text. Importantly, Ligeti expanded the roles of Prince Go-Go’s two ministers. While Bálint Szabó and Kevin Conners provided humorous moments as the Black and White Ministers respectively, the dramaturgy highlights one of the most important dimensions of Ligeti and Michael Meschke’s libretto: the corrupting allure of political power. The ministers mock their leader Prince Go-go, placing copies of their constitution as a type of heavy crown while ripping out pages of it. They refuse to “put the interests of the nation” above their “selfish egoism” and snidely call for appeasement, another historical reference to cowardly politics. The ministers’ plans for preventing the apocalypse inevitably fail; their fraudulent policies mirror Nekrotzar’s own role as a false prophet conducting a sham apocalypse.

This political and historical dimension remains present in the Munich production. Yet Warlikowski seems to love ambiguity. While never providing an explicit historical context for his staging, Warlikowski states in an interview that the opera “is not about Chernobyl,” a slight dig at Peter Sellars’s infamous 1997 Salzburg production which Ligeti famously disavowed. This production comes nowhere close to visually reproducing Brueghel- and Hieronymus Bosch-like fantastical paintings, though it ingeniously channels a key aspect of Ligeti’s oeuvre: the struggle with memory and trauma. In the same interview, Warlikowski admits the struggle of trying to “make sense” of Ligeti’s theater of the absurd. By hinting at the opera’s autobiographical elements, Warlikowski leaves it largely to the composer’s music and text to try to have it “make sense.”

Le Grand Macabre follows a trend within the Polish director’s recent work in Munich. His Tristan und Isolde is full of references to Sigmund Freud, and more recently his pairing of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Schoenberg’s Erwartung emphasized the latter work’s similarly Freudian nightmarish dreamscape. In Warlikowski’s staging of Erwartung, two corpses resurrect in the final moments of the monodrama. In his Salome, we see Jochanaan wandering around stage and smoking a cigarette even after he has been supposedly beheaded. Resurrecting corpses, however, are written into Le Grand Macabre’s libretto and part of the original play. This makes the Munich production of Ligeti’s “anti-anti opera” particularly powerful.

In a 1990s French documentary, Ligeti described the return of his mother from Auschwitz (where his father died) as a “total shock” for him since he thought she had been murdered as well. Yet he also admitted that a direct examination of his emotional response to his wartime trauma would be “pathétique and sentimental.” Like with Warlikowski’s Salome, we see figures sitting in chairs already before the work starts. In this case it is Death himself, named Nekrotzar, who sits silently and watches as people enter a bare, concrete room, akin to a school gymnasium or departure hall. The parallels between the two productions continue as Nekrotzar’s infernal retinue, fitted with animal-head costumes (perhaps a reference to Art Spiegelman’s Maus), sit in a row on the side of the stage and watch the destruction of Breughelland. In his Salome, we see a group of silent characters sit in the exact same way when the title character does her veil dance with a personification of death.

?si=x274Hrb1b9Jl7wNN&t=1138

Another regular feature of Warlikowski’s productions is his use of extratextual film projections. For example, his production of Franz Schreker’s Die Gezeichneten also contains animal-head silent choruses, as well as projected images of another silent film, Frankenstein, to mirror the title character’s search for love despite his physical condition. As in the case of Schoenberg, the Nazis had banned Schreker’s music, also Jewish, one year before his 1934 death. Yet in Le Grand Macabre the film clips developed by Warlikowski and Kamil Polak are more subtle. The screen is especially prominent above the stage during the third scene when Nekrotzar and his retinue prepare for Judgement Day.

During the interlude when the asteroid arrives, a large screen projects Earth’s destruction in a reference to Lars von Trier’s Melancholia. When Nekrotzar boasts how he has “demolished kings and queens in scores.” Warlikowski and Polak include clips from silent films like F.W. Murnau’s Faust (a devil coming to Earth), the Odessa Steps scene from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (also referencing a Tsar), D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance with the fall of Babylon and the Huguenots’ deaths in the St. Bartholomew Day’s Massacre (Catholic repression), as well as Abel Gance’s Napoleon (the appeal of populist leaders). Right before he collapses drunk, he lists Caligula, Theodorich, Ghenghis Khan, Ivan the Terrible, and Napoleon Bonaparte as great leaders he has slain.

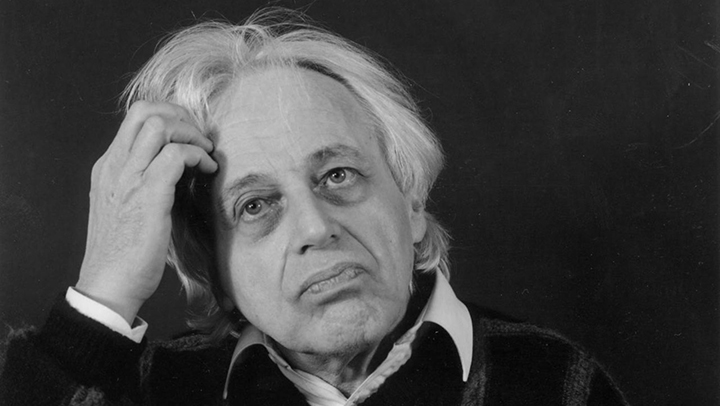

Yet after showing images of the French emperor from Gance’s 1927 film with its famous triptych split-screen shots, a brief image shifts the tone dramatically. In the most jarring instance of the production’s autobiographical reading, Warlikowski synthesizes his clips from silent films that follow Nekrotzar’s lines with images of Ligeti himself. After frequent cuts from Griffith and Gance’s films, the screen above the stage freezes on an image from a 1990s French documentary about the composer: Ligeti as a child with his younger brother with the subtitles “I used to think I would be a great scientist and win a Nobel Prize.”

This image of György and Gábor Ligeti as children in the original documentary occurs after Ligeti describes his brother’s death in the Holocaust (murdered in Mauthausen). In addition to his childhood scientific aspirations, Ligeti also wanted “to discover the secrets of life and become a great composer”, though he realized as a teenager he could not do both. As Ligeti admits this in the interview, the documentary shows Ligeti’s drawing “Die Bevölkerung in den Wolken.” This 1967 picture, which depicts an apocalyptic scene containing fantastical creatures devouring each other, was part of the composer’s reflections on his childhood imagination and fears. These memories were also reflected in his music from the time, especially the opera.

In the first drafts of the opera, Ligeti considered calling it “Kylwyria,” the fantasy world he had constructed as a child, in part as an escape from the social and cultural upheaval of his youth. While these details are not included in Warlikowski and Polak’s video projections, they offer insight into how Ligeti’s dreams and aspirations were on a collision course with history itself. Rather than end up as one of the most famous leaders in history, Ligeti’s career pivoted towards music — the opera itself as ironic and metaphorical reflection on mortality and his own past. Warlikowski’s inclusion of this autobiographical element, juxtaposed with Nekrotzar’s lines, aligns with the composer’s own insistence that the opera centers on corruption caused by power.

Ligeti’s Last Judgement is “terrible and imaginary.” Nekrotzar is vampiric yet ultimately fails at his task of bringing destruction to Breughelland. Or is this apocalypse still real? When, for example, three soldiers harass Prince Go-Go and ransack the left behind luggage, Warlikowski has them dressed like black-shirt paramilitaries — are these neo-fascist figures bent on erasing the memory of apocalyptic tragedy? Furthermore, although the libretto states that Nekrotzar “stands motionless for a while, then begins to shrivel up, collapses, becoming smaller and smaller, turns into a sort of sphere, shrivels up further and finally disappears, becoming one with the earth,” in this production he returns to his office chair, back at his desk as he was at the beginning of the work.

Astradamors asks “was he true death?” and Go-Go questions whether “he was mortal just like us.” As in the libretto, in the final scene Astradamor’s abusive wife Mescalina, the ministers, and the three soldiers rise up from their supposed deaths. They grab lawn chairs and join Piet and Astradamors. While the text specifies that “only Nekrotzar remains absent” here is off to the side, looking on. Yet in the closing moments of the work, all of these characters return to sleep—or death—echoing Warlikowski’s decision to have Salome’s cast drink poison and commit mass suicide in the face of the impending arrival of Nazi executioners in that opera’s final bars. While his approach to Strauss’s work was much more overt in its historical periodization to the point of risking Holo-kitsch, his Le Grand Macabre is more effective precisely in its subtlety in line with Ligeti’s own polystylism and obfuscation of autobiographical elements in his music.

In the behind-the-scenes interview for the production Warlikowski curiously states how the notion of the apocalypse and Judgement Day was a Christian invention which “introduced something very strong for our imagination,” and, in a companion essay, describes how “governing with fear is a strategy once practiced by the Church and now by the populists.” Contemporary political and religious dynamics are therefore part of what drives Warlikowski’s interpretation of the work. In some ways these ideas mirror Ligeti’s own approach to Christian themes in his music.

In the 1990s documentary, the composer describes wartime restrictions on Jews in Hungarian schools and the paradox of him a “non-believer but not an atheist” using Catholic texts like the Requiem Mass. His Requiem is full of “hatred and fear,” even “demonic,” combining multiple texts in a rich, micropolyphonic style. Ligeti then states that Le Grand Macabre functions in the same manner, in essence a “second Requiem” about the fear of death, though now combined with humor. His Requiem went beyond Catholic liturgy, it “hid other things” like his “revolt against Nazism and Communism.”

?si=J16lKQW9kcc4yqgr&t=145

The opera also obscured its many themes by combining the seriousness of the Requiem with elements from the absurdist, dada-inspired Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures (written around the same time as the earlier choral work). This death-drive and references to religion are not only found in the two “requiems.” For example, musicologist Volker Helbing has theorized that Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, particularly its intermezzo, as a “large-scale process of annihilation,” which speaks of the composer’s role as “double survivor”: a refugee escaping political repression in Stalinist Hungary in the aftermath of most of his family’s murder in the Holocaust. Many of Ligeti’s works, including the concerto and the opera, feature “lamenti,” wailing descending motifs akin to Dido’s famous aria in Purcell’s opera. As Helbing has argued, such autobiographical “annihilation” works alongside moments of genuine “humorous, non-emotional attitude.”

While Warlikowski shows the documentary footage of the composer during a particular ferocious “lamento” as the comet supposedly strikes Breughelland, the staging Le Grand Macabre also retains many of the comic moments. Kent Nagano’s precise conducting embraced the score’s mix of humorous irony and gravitas. The climactic moments such as the “lamento” earthquake right before the clock strikes midnight were truly deafening—musical jump-scares for the Munich audience. Nagano also gave ample room for Astradamors (Sam Carl) and Piet (Benjamin Bruns) to relish their wide-ranging tragi-comic lines. A particular highlight was Sarah Aristidou’s acrobatic (physically and vocally) portrayal of Prince Go-Go’s secret police chief, which brought out Ligeti’s self-referential meccanico style through the singer’s meticulous enunciation of repetitive syllabic text. Thus, while the production risked feeling heavy handed in its apocalyptic vision and historical references, the overall performance was still in line with Ligeti’s intention of creating a poly-stylistic blend of fear and comedy.

At the end of the same documentary quoted by Warlikowski Ligeti states “I haven’t become Western but rather someone who lives in both worlds. In my heart I am at home everywhere…a world citizen. But I am bound to Transylvania, where I haven’t been in 36 years.” Returning to Scheding’s warning against reducing Ligeti to solely a Holocaust survivor, Ligeti’s polystylism reflects his grapple with his Hungarian, Transylvanian, Romanian, Austrian, Jewish, and ultimately global viewpoint and identities. Warlikowski’s subtle refences to Ligeti’s own reflections on death and memory are an important dimension to the new production, thought ultimately are just some of many ideas audiences are left with.

Ligeti himself, through his collage of musical styles and mix of somber and humorous scenes, concludes the opera with an ambiguous yet cautiously optimistic message: “No one knows when his hour will fall! Farewell, ’til then in cheerfulness!” Perhaps Warlikowski’s vision does not seem the most cheerful rendition of Ligeti’s masterpiece. Yet, by acknowledging Ligeti’s own autobiographical grappling with the work’s core themes, the evening ended on a somewhat somber though nevertheless cautiously optimistic tone. As Ligeti’s only opera, Le Grand Macabre offers an important testament to the composer’s own complicated, at times contradictory identity and compositional style. While perhaps shocking to a first-time listener, the opera is deeply deferential to art form’s long tradition and speaks to Ligeti’s own reflections on history. It ultimately affirms opera’s possibility as a vehicle that can teach us lessons about humanity’s resilience in the face of pure evil.

Photos: Wilfried Hoesl

Comments