Videos of Bartoli singing the arie antiche I studied in the my voice lessons led me to Netrebko serenading Scorsese at the Kennedy Center, then to the promotional clips The Metropolitan Opera posted weekly, and then to older clips: Bumbry as Carmen, Corelli in Il trovatore, and more. There were soaring voices aplenty, matched by Cecile B. DeMille-style sets and many an ill-judged caftan. These clips were my daily dose of the glamorous and grand. They were a fantastical escape from the drudgery of being a middle schooler in suburban New Jersey.

It was not until I stumbled upon the Bayerische Staatsoper and its channels, however, that I discovered that opera could be interesting.

The productions they previewed in sleek trailers were dark, weird, and entrancing. Industrial wastelands and midcentury modern interiors with moody lighting replaced castles and pagodas. Supernumeraries stalked about the stage in animal heads like the characters in Times Square. The diva did not swan about; she took a drag from her cigarette. I found regietheater. Even if I did not fully get it or agree with what I saw, it sustained my interest in the artform alongside those vintage clips. What I discovered on that channel made opera feel not only fantastical but vital and evolving. (Take that, Against Modern Opera Productions!) So, when my friend and fellow critic Emery Kerekes suggested I join him at the Munich Opera Festival, I jumped at the opportunity. It felt only right that I should move beyond my laptop and see the genuine article in person.

I have already written about two performances I saw at the festival, but my visit began with Richard Strauss’s Elektra. If I was slogging through a wave of jet lag going into the performance, the outstanding quality of the Bayerisches Staatsorchester under the baton of current Generalmusikdirektor Vladimir Jurowski kept me from succumbing to my dysregulated clock. Their playing was cohesive throughout, capturing both the magisterial sweep and the piercing intensity of the score. Jurowski finessed each of Strauss’s motifs to shape the dramatic thrust of the piece towards its blood-spattered conclusion. His approach retained the tension in score without overwhelming the voices or leaning too heavily into bombast. Certain music directors could learn a thing or two.

The late Herbert Wernicke’s production has certainly served the Staatsoper well since its 1997 debut, blending classicism with minimalism. The set consisted of a single raised platform at stage right and a large staircase representing the palace that sits behind an imposing black scrim. The scrim, which forced much of the action to the apron of the stage, rotated inwards at a diagonal, a dark gash against the stark, scarlet-cast realm of the palace.

Likewise, the action was stripped to its essentials. Elektra spent much of the evening pinned down by a spotlight upon the platform and cradling her axe as if to emphasize her ironic lack of agency within a story bearing her name; she is, after all, entirely dependent on her siblings to do her bidding and fulfill her desire for vengeance. The costuming underscored the opera’s gender politics: the largely passive women are clad in vaguely Grecian attire, while the more active Orest and his tutor don noirish suits. There were some metatheatrical touches too, such as Klytaemnestra cloaking herself in a replica of the National Theatre’s red velvet curtains and Orest climbing out of the box closest to the stage to make his entrance. It was elegant and effective, and its core directorial ideas have remained clear.

Likely due to how the production hems her in, Elena Pankratova was not the most dynamic Elektra, but her soprano was robust and secure across her register. While she launched quite a few impressive top notes into the auditorium, she was at her best during the teasing sections of her encounters with Klytaemnestra and Aegisth, where she infused a sardonic girlishness into her tone. Vida Miknevi?i?t? made for a particularly vital Chrysothemis as her silvery, tightly wound vibrato sliced through the orchestra with ease. Her blazing cry of “Orest ist tot!” was among the highlights of the evening. As Klytaemnestra, their mother, Violetta Urmana, who seems to have been the festival’s resident hag whisperer, was a stately presence, sneering rather than snarling out her insults towards her daughter and lackeys. She approached her dream narration with delicacy, which allowed us to glimpse the frightened woman behind the regal veneer. Bass-baritone Károly Szemerédy was a steely Orest, while tenor John Daszak served ample bluster as Aegisth. Yajie Zhang stood out from the chattering chorus of maids, her mahogany mezzo-soprano curdling with vehemence.

To mark the centennial of Hungarian maverick György Ligeti, the Staatsoper presented its premiere production of his sole opera Le Grande Macabre, an absurdist romp through an impending(?) apocalypse and the annals (and I mean that in its full anal sense) of operatic convention. The score careens gaily from a car horn ode to Monteverdi to direct Offenbach and Stravinsky quotations, before taking the piss out of bel canto, especially in its handling of coloratura vocal writing. Former Generalmusikdirektor Kent Nagano capably guided the orchestra and singers through Ligeti’s swirling rhythmic web and shifting tonalities, plumbing considerable dramatic depth and menace from the score’s surface jokiness.

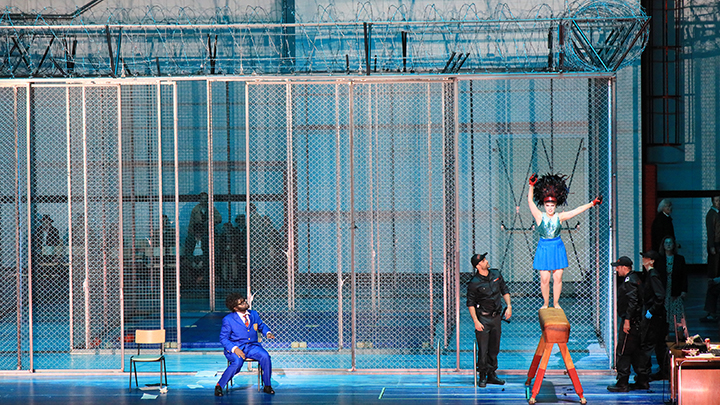

Krzysztof Warlikowski’s production mirrored Nagano’s approach in the pit: his Breugelland was fully immersed in the apocalyptic if it had not already been dwelling there for some time. The set by frequent Warlikowski collaborator Malgorzata Szczcsniak fused the waiting room in an Eastern European train station with a Soviet gymnasium, replete with a pommel horse. Barbed wire-topped fencing rearranged itself to mark locations changes and caged the chorus in as the situation grew direr. Supernumeraries in demon bunny balaclavas and flesh-toned prosthetics that transformed them into uncanny cat-rodent hybrids promenaded as smoke poured out of the wings—a mark on my Bayerische Staatsoper bingo card.

The lovers Amanda and Amando, played here by Seonwoo Lee and Avery Amereau, were portrayed as two female influencers training their selfie-stick towards their bandaged faces, suggesting they had undergone some cosmetic procedure. A screen above the stage livestreamed their ecstatic paeans to love, which were directed at themselves rather than at each other, as they descended beneath the stage. Prince Go-Go preened about the stage in spiffy English tailoring, evoking many an inept, self-interested politician. The blind decadence and vanity of this world had brought it to the brink as monsters spewed out of its fissures.

Despite its considerable atmosphere and the strength of its imagery, the production fell short in honoring the humor of Ligeti and Michael Meschke’s libretto. There were a few lighthearted touches, such as Venus’s appearing in a Björk-style swan dress, but a sense of self-seriousness undermined their effect. A few computer screensaver-esque projections of the incoming comet elicited some unintended guffaws. But even the opera’s many sexual escapades felt unfun. Still, a photo montage projected above the sage of the young Ligeti with his family members, most of whom were killed in the Holocaust, as the Passacaglia finale unfurled was a moving tribute to the composer’s resilience and spirit.

The singing was uniformly strong. French-Cypriot soprano and contemporary performance specialist Sarah Aristidou fearlessly tackled both Venus and Gepopo with precision, retaining consistency of tone and excellent diction even as her roles brought her into her vocal stratosphere. Benjamin Bruns brought an appealing brightness alongside a healthy dose of sleaze to the drunken Piet the Pot, executing his mock prayers and hiccupping rant in the first scene with aplomb. As the perpetually emasculated Astramadors, Sam Carl handled the role’s frequent leaps into the falsetto well, even if his bass-baritone lacked distinctive coloring.

Playing his domineering wife Mescalina, Lindsay Ammann laced her chestnut-hued mezzo-soprano with spite, infusing her performance with a level of off-kilter camp the evening sorely needed. She delivered her plea to Venus for “one lascivious night” with passionate sincerity. Countertenor John Holiday suffused his portrayal of Prince Go-Go with a sprightly, attractive tone, offering some genuinely lovely singing amid the chaos. Baritone Michael Nagy as Nekrotzar, the embodiment the Macabre, started off sounding a tad lean but mustered enough power to make his pronouncement of the Day of Judgement at the end of Act II truly startling.

The festival then transitioned from one tale of a society staring down divine judgement and its imminent destruction to another with Mozart’s Idomeneo, which premiered in Munich in 1781. English maestro Ivor Bolton, a foremost interpreter of Mozart, led the orchestra. For the most part, he kept the tempos lithe and bouncy, drawing a maritime swell from the score as well as some focused playing from the orchestra. The concluding ballet music was a dynamic display of contrasting dynamics and moods. He did have a tendency, however, to cover the singers.

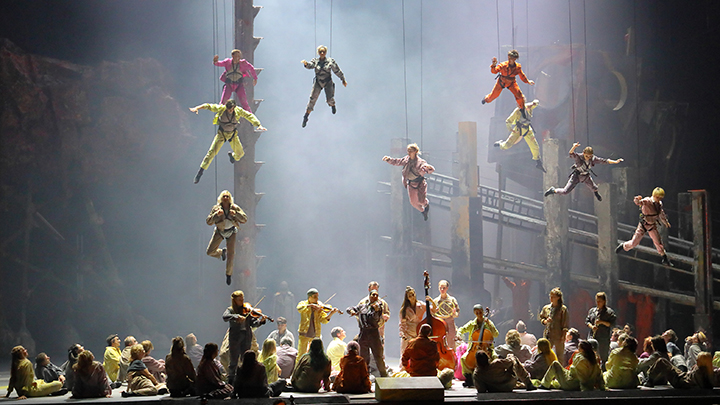

The production by Antú Romero Nuneswas was admirable attempt to reorient an opera that is primarily concerned with the foibles and divine entanglements of the ruling elite towards the communities they profess to lead. The production opened with the sound of rainfall as a mysterious voice intoned, “Prostatevi dinanzi a Dio”: a call for Idomeneo to relinquish his power and pride. The curtain rose to reveal the king listening to a string quintet playing excerpts from the larghetto movement of the ballet music from a regal if isolating distance. The chorus and even a few of the principals wore brightly colored jumpsuits and work boots and engaged in various welding and building projects across Phyllida Barlow’s sculptural sets, which evoked a collection of wharves and piers that had been weather-beaten and storm-tossed into abstraction. We got the sense of a community coming together in the wake of devastation to rebuild, only to be confronted with yet another disaster brought on by their leadership. Misty lighting by Michael Bauer suggested the storms behind and ahead. Choreography by Dustin Klein emphasized looseness of form and had the dancers build off each other’s movements to create a unified whole.

Having once sung Idamante transposed for tenor at the Bayerische Staatsoper, Pavol Breslik graduated to the role of the titular father here. His tenor has matured and darkened in recent years, but there is still a freeness and freshness to the top of his register. He displayed ample vocal dexterity along the tricky tessitura of his first aria “Vedrommi intorno,” but “Fuor del mar” in the second act proved more challenging, as his tone and audibility diminished in the aria’s lower-lying reaches.

Emily D’Angelo returned to this production as Idamante. To my ears, it took a while for her mezzo-soprano to lock into place; her “Non ho colpa” sounded muffled throughout, and her sound remained subdued until her top notes had opportunity to bloom towards the end of “Il padre adorato.” From there, her voice began to warm gradually. Still, her dramatic presence often compensated, and she imbued an adolescent anguish in her portrayal of the conflicted prince. She was riveting during the sacrifice scene, as her dramatic and vocal intensity finally came into alignment.

Olga Kulchynska made for a charming Ilia, spinning some luscious, floated lines “Zeffiretti lusinghieri.” Her voice blended seamlessly with D’Angelo’s during the ethereal duet “S’io non moro a questi accenti.” Hanna-Elisabeth Müller’s crystalline soprano navigated Elettra’s transitions between the viperous coloratura of “Tutte nel cor vi sento” and “D’Oreste, D’Ajace” and more gentle legato passages of “Idol mio” with ease and an attentiveness towards proper Mozartian style. Jonas Hacker impressed with his robust tenor as the advisor Arbace—he has the makings of a first-class Idomeneo—while bass Alexander Köpeczi added gravity to the proceedings in his off-stage appearance of as the Oracle of Neptune.

Special mention goes to the Chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper under the direction of Christoph Heil for their strong performances across these three operas, but especially in Idomeneo, where they evoked a range of colors to amplify the score’s shifting dramatic moods.

Photos: Wilfried Hoesl

Comments