First a 1993 book by Sister Helen Prejean, then a 1995 Tim Robbins film, Dead Man Walking follows the journey of Sister Helen as she, after exchanging letters with convicted murderer Joseph De Rocher (a pseudonym) in Louisiana’s Angola Prison, decides to accept his request for an in-person visit.

As she becomes Joe’s “spiritual advisor,” Sister Helen faces wrenching moral questions not only about the death penalty, but also profound issues involving forgiveness, redemption, and salvation. McNally’s taut libretto tells the story mostly through a series of intimate, two-person scenes that are exquisitely personal. Heggie’s fascinating score is sometimes Southern in rhythm, sometimes jazzy, sometimes beautifully transcendent. Above all, the music perfectly reflects the emotional landscape of every scene.

The opera opens with a brutally realistic depiction of the crime of De Rocher and his brother, who come upon a teenage boy and girl, naked from skinny-dipping. The De Rochers grab the couple and begin raping the girl. When the girl continues screaming, Joe De Rocher viciously stabs her to death and the boy is shot dead.

This scene is perfectly choreographed by fight director Chuck Coyl and “intimacy director” Tonia Sina. The scene is shockingly graphic, accompanied mainly by pop tunes emanating from the radio of the teenagers’ car. But it is vital that we see Joe De Rocher’s crime in order to understand his journey to Death Row.

This scene is immediately followed by a bright scene in Hope House, where Sister Helen is surrounded by singing children who are in day care with the Sisters. After the children’s parents pick them up, we first learn that Sister Helen has decided to visit Joe at Angola. It is here that Sister Helen’s physical and emotional journeys really begin.

Dead Man Walking offers no easy answers, and that is its greatest strength. It is not written to support a particular point of view about the death penalty or anything else; instead, it presents both sides of the moral quandaries and asks the audience to consider how they would react.

The best example of this is a scene where De Rocher’s case is made to the Pardon Board, with the Sisters on one side and the parents of the murdered children on the other. In the center is De Rocher’s bewildered and frightened mother, trying to find good in her son by recalling his innocent childhood deeds.

Susan Graham gives an astonishing performance as the mother, stripped of her natural glamour and utilizing a defeated physicality. She sings splendidly and acts with great emotional depth. I will not soon forget her repeated cries “Haven’t we all suffered enough?”

In a later scene where she says goodbye to Joe just before his execution, she desperately tries to smile for him. She can’t quite do it and her eyes fill with tears. It’s one of the most deeply moving moments in an opera full of them.

The opera ends with Joe’s inevitable execution by lethal injection. The execution is slowly and graphically depicted, a nurse entering and hooking up IVs that will carry the lethal potion into Joe’s veins. The orchestra is completely silent. The only sound is the beeping of Joe’s heart monitor. No one in the audience coughs. No one shuffles in their seat. It was as if the audience was holding its collective breath. When the heart monitor finally flatlines, it is a cathartic moment.

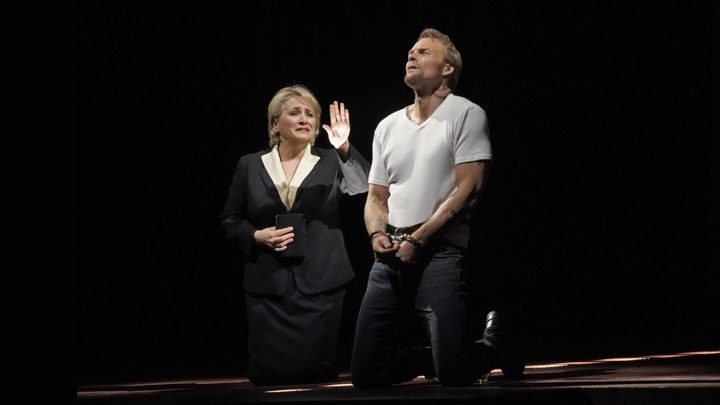

Patricia Racette is a moving Sister Helen, and her spiritual journey is beautifully crafted. She sings with full-throated tone and a wide variety of vocal colors and volume changes. I was particularly struck by her insomniac, increasingly desperate struggle with the nature of forgiveness and her own ability to forgive Joe. She finds no peace until Joe finally confesses, after she insists “The truth will set you free.”

Bass-baritone Ryan McKinny’s Joe is a volcano of anger and frustration, and finally terror as his execution nears. McKinny gives a profound physical performance and sings with power and emotional depth. His wrenching confession scene is the emotional climax of the opera. He moves with knife-like grace and it is a truly dangerous performance. The audience never knows when he’s going to explode.

Also excellent is plummy-voiced soprano Whitney Morrison as Helen’s friend and confidante Sister Rose, particularly good in the scene where she plays the foil to Sister Helen’s middle-of-the-night dilemmas.

It is a tribute to Lyric Opera of Chicago that even the smallest roles here are cast from strength. Lauren Decker, Talise Travigne, Allan Glassman, and Wayne Tigges as the embittered parents of the murdered children all give fine, three-dimensional performances, especially Tigges as the girl’s father, furious at the Pardon Board meeting yet touchingly vulnerable as the execution nears.

Eric Ferring and Ethan Warren are touching as Joe’s younger brothers, trying to comfort Joe and their mother. Gordon Hawkins sings powerfully as the driven Prison Warden.

Christopher Kenney has a delightful moment as a traffic cop who stops Sister Helen for speeding, then can’t quite bring himself to give a ticket to a nun. It’s a much-needed moment of comic relief. Desiree Hassler and Corinne Wallace-Crane have lovely cameos as Sisters Catherine and Lillianne.

Contemporary opera specialist Nicole Paiement conducts with precision and great attention to detail, clearly right at home with Heggie’s musical landscapes, and the Lyric Opera Orchestra responds with beautiful and clean playing.

There are only a few performances left of Dead Man Walking in Chicago. If you’re in the city or anywhere near it, you owe it to yourself to see this riveting, whip-smart production.

Photos: Ken Howard

Comments