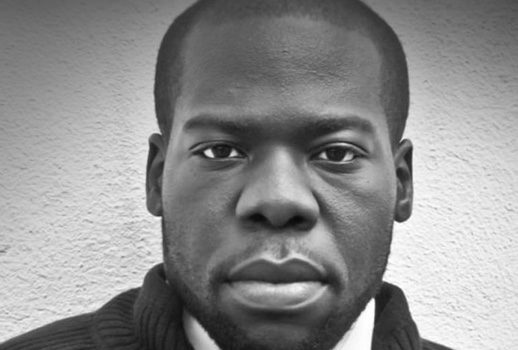

“Rich, well-metaled … tirelessness” tenor Errin Duane Brooks as Jean

New York was once a truly swinging opera town, with two major repertory companies (discreetly rivals) and one or two major league concert opera companies. The concert companies performed three or four items of forgotten repertory starring little-known foreign stars or local stars who wanted to attempt obscure roles. It was a great deal, with the American Opera Society and its successor, Opera Orchestra of New York. Then the audience got old and the money dried up.

Can this sort of scene come back? Can it come back with less money? Can it find the audience of opera lovers who grope for sustenance in the dark like Papageno, bored with the Met’s stodgy repertory and inexplicable casting choices? Washington has a concert opera, Baltimore has a concert opera, Boston has Odyssey, which alternates staged and concert performances. Why not New York?

One candidate brazenly proposing itself is New Amsterdam Opera, which at this point can only manage one big event a year. Last Friday, in this, its fourth, season, NAO gave Massenet’s Hérodiade at The Center at West Park (86th and Amsterdam), a deconsecrated church with warm acoustics and dazzling Romanesque stuccos.

I wish their advertising were more effective (the venue was full but not packed), but there was nothing the least bit slapdash about the thrilling performance of this curious score.

Hérodiade had not been heard in New York since 1981, when OONY presented it at Carnegie Hall—memorably, the night Montserrat Caballé and Nicolai Gedda both cancelled. (Awilda Verdejo sang Salomé, and very satisfying she was.) Eve Queler retained the orchestra parts, which she bestowed on New Amsterdam Opera with her blessing.

Massenet had not yet found himself in 1881.What he found instead was the rather dated grand opera style of Meyerbeer and Gounod. He threw in some orientalism left over from Le Roi de Lahore (including Hebrew prayers, sung by an offstage cantor in the Second Temple), and a tenor saxophone because Adolphe Saxe had just invented it and no one knew what to do with it yet.

The score, with its chaste love duet for Salomé and John the Baptist (Jesus himself is never mentioned), played well to the pious, unspecific religiosity of the nineteenth century, a fashion later adopted in many a Hollywood Biblical spectacular.

Lord knows where Massenet’s librettists got their plot—quite possibly they made it all up. The sources say they drew on Flaubert’s novella, but the two tales have nothing but their title in common. Flaubert was the source, rather, of the plot of Wilde’s Salome (and thus of Strauss’s Salome) and also of the film starring Rita Hayworth. But not the Massenet.

In Massenet’s opera, Herodias abandoned her child at birth (paternity unspecified) in order to marry King Herod, whom she adores. He, however, is obsessed with a girl he has seen dancing in the market, a girl named Salome, who never does dance for us. She spurns Herod’s lust because she is devoted to a prophet named John, with whom she is in love.

John denounces Herodias’s depravity but never (in our hearing) explains what she has actually done to set him off. She’s just a generic Jezebel. But she wants him killed. Herod prefers to use John to aid him in a popular uprising against the Romans, but John won’t play ball.

Salome begs the queen to help her save the prophet, mentioning that she’s just a poor girl abandoned by her own mother at birth. Shock! Recognition! “I am—your mother!” But it’s too late—John has been executed at jealous Herod’s order. Salome falls dead of—well, you know, it’s an opera. That disease.

Along the way, we get processions (religious and military), erotic hallucinations (Herod takes drugs—I think NAO cut a ballet or two, happily), and famous arias for almost everyone but Hérodias, poor girl, snubbed not only by her daughter and her husband but by her composer. She does get a couple of powerhouse duets.

The only excuse for putting this farrago on is four or five terrific singers and a first-rate orchestra. If you want something that makes sense … there is Massenet’s next opera, Manon, or the one after that, Werther. He was on the brink of finding himself when he wrote Hérodiade. He needed to learn how to choose librettists and get over the grand opera model—though he came back to it for Le Cid and Esclarmonde.

New Amsterdam specializes in American singers whose abilities are as yet little known. There are great voices out there, real voices, but we haven’t heard them. In Hérodiade, we heard several. They were shockingly good.

There was a settling into pleasure as Phanuel (priest and astrologer), Salomé, Hérode and Hérodiade presented themselves in an Act I chock full of exposition (and also Salomé’s aria, “Il est doux, il est bon”). But then Errin Duane Brooks, as Jean, came in looking wrathfully at all us sinners, and hurled out a voice like warm steel, superbly controlled to its highest notes (the role rides high and forceful—Jean de Reszke sang it).

Everyone in the room sat up straighter. We could not believe what we were getting: the rich, well-metaled quality of the instrument, Brooks’s tirelessness through a long night.

Clearly the voice is large enough for any hall (Brooks will make his Met debut on Opening Night next year in Porgy and Bess—a thousand pities he wasn’t there for Samso nor Aida this year), but—the question is unavoidable—can he sing softly as well as forcibly? He answered this during his long monologue in prison in Act III (“Adieu donc, vains objets”), and the tender duet with Salomé.

Brooks can seduce as well as denounce. Four of us, out for drinks after the performance, spent the time daydreaming aloud of roles we thought he should undertake. Douces images!

His Salomé, Marcy Stonikas, has a gleaming soprano of lyric quality but dramatic power. The mid-voice is secure and of a lovely color; the top takes some warming up—breathy in the first scenes, she filled it out over the role’s exceptional compass later on.

Jason Duika has a sizable and remarkably lofty baritone, which should serve him well for Verdi roles—he topped “Vision fugitive” with an A-flat. And yet his delivery seemed effortless, lyric, a melting, manly sound.

As Hérode, he had to be quarrelsome with some, conspiratorial with others, and he sang the recits as if they meant something. “Vision fugitive,” in which he apostrophizes the girl of his (drug-induced) dreams, shows Massenet already had an affinity for such emotion. Des Grieux, Werther and Athanaël sing arias in the same emotional key.

Janara Kellerman’shefty mezzo soprano ran an emotional gamut in the title role. She held her own in concerted passages but the composer seldom places her center stage. She did have a nifty duet, though, with the priest/astrologer/Jacques-of-all-trades Phanuel, Isaiah Musik-Ayala’s fine growling bass. A pretty light soprano named Brooklyn Snow sang a pretty little solo to induce Hérode to take a little … something. And everyone’s French diction was top notch.

Keith Chambers, the company’s artistic director, led the orchestra—string light (one double bass!), brass heavy—in a performance with few ragged patches. The brasses came in ominously, the saxophone was startling, the oriental harmonies (aided by a small but ardent chorus) set the scene, we got our money’s worth. As with his work on La Favorita and Forza del Destino, Chambers made the case for grand opera as great theater.

The list of donors included gifts in memory of Caballé and Brian Kellow. I suspect they would have been delighted. It’s just the way I’d want to be memorialized.

Comments