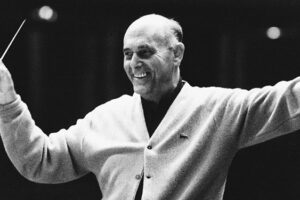

The ostensible mission of director Dmitri Tcherniakov and conductor Daniel Barenboim (frequent collaborators) is to conjure a Tristan for now; ergo, it is “non-traditional.” Is it “Regietheater”? That possibility would certainly raise the knee-jerk hackles of many current opera goers who deplore their notion of “Regietheater” and “Konzept” productions as arbitrary and decadent.

In this case the mode of presentation is precisely what makes the production fresh, relevant, and revelatory. The “Konzept” (if there is one) is to present the opera in the visual and dramatic language of up-to-the-minute top-drawer television (HBO, Netflix, Amazon Prime, where all the best things are happening) the better to convey what it means now.

But that is not to say that Tcherniakov plays fast and loose with the libretto. Despite the visual and dramatic language used, he hews surprisingly close to Wagner’s stage directions, of which there are very few. The sui generis English horn solo is played from the stage, as Wagner indicates.

But page after page after page of dialog is exchanged without a single stage direction, like a Bach autograph without tempo or dynamic markings. A director must either let the singers park and bark, oratorio style, or take “liberties” in order for something to happen on stage.

Tristan opens with the conflicted atonality of the “Tristan chord” and for the next four hours suspends its resolution by twisting and teasing it until the absolute last moment, making “Tristan” the longest deferred—suspended, musically speaking—orgasm ever. But where is the orgasm?

At the climax of the most overtly sexual music in opera, the act 2 “Liebesnacht” duet, that isn’t Isolde screaming in orgasmic ecstasy. It is Brangane screaming in startled horror as the lovers are discovered in flagrante delicto. What exactly are the lovers doing at that precise moment?

Act 1 is set in the saloon of a luxurious superyacht with chic modern décor, a low table littered with bottles of top shelf liquor and half-empty glasses. On the right, a large flat screen CCTV monitors the ship’s prow and surrounding seas. A group of officers sit around a low table. The youngest of them, a sailor in blue cardigan and navy blue necktie, sings a song that offends Isolde. Her rage whips through the first act like a hurricane.

By Act 1, Scene 5, Isolde, doubly betrayed by Tristan, is desperate for revenge and running out of time. She is crazed because she couldn’t kill him when she had the chance. She tells him she wants to kill him and dares him to drink her “cup of expiation.”

Tristan—Eagle Scout-Warrior-Jock, “the most loyal of the loyal,”—is consumed by guilt for what he did and anguish for what he didn’t do. Isolde proffers her cup of peace to a Tristan lost in a trance, a fever-dream projected on the blacked-out stage: the precise instant when Isolde saved his life with a healing potion.

The sailors announcing landfall startle Tristan from his trance. He asks where he is? “Near the end,” Isolde replies, still holding out the cup. The sailors shout again. She taunts him into drinking what she believes to be their death.

Tristan drinks with the “bring it on” swagger of a buttoned-down corporate warrior fatally afflicted with a renegade heart. Before he finishes the potion Isolde rips the cup from his hand and drinks her draught of death to join their fates.

The potion comes on slowly, in near silence from the pit. Seated at opposite ends of the long table they both are both overcome by a spell of woodwinds and muffled drums. They awake to the Tristan chord. The potion was not poison. They are not dead. They are alive with love for each other. The potion has flipped a fatal switch that cannot be undone.

They gaze at each other, wonderstruck. They speak each other’s names, realizing they are desperately and irrevocably in love. Tristan is a frat boy unhinged by love too big to comprehend. Isolde is a vengeful fury-cum-dazzled lover.

As the offstage chorus hails King Marke’s arrival the lovers burst into wild laughter. It is shocking and stunning, infectious, giddy and ecstatic. Brangane, appalled and astonished, scolds them to no avail. They are drunk on love. The world of ships and kings and cups and swords has become nothing more than a trap to escape.

The second act love duet is a stolen night between adulterous lovers, a private party with festive wine and hors d’oeuvres. Wagner’s “garden with tall trees” is a decorative motif, the wallpaper of the plush salon where well-heeled guests drink before the hunt.

When the lovers are finally alone, Isolde is torn by the contradictions of their love. Tristan exhorts her to yield to the irresistible with boyish earnestness and macho bravado. He pulls together two upholstered chairs, a little bit of stage-managing, so they face each other during a long orchestral passage where he silently enchants the enchantress with his eyes and hands. As they resume singing he waves his hands, conducting her, bringing their mutual passion into accord.

Anja Kampe and Andreas Schager perform here at the peak of artistic expressiveness, objectifying the beauty and anguish of the music. They are familiarly realistic and impossibly poetic, he in a sober tuxedo, she in a sheath of emerald green.

He is charmingly seductive; she is alluring and radiant. During Brangane’s warning the stage is again eclipsed with projections of their first tender touch. Brangane warns them to no avail. The lights come up and they are deep in a trance.

Isolde awakes first. She tentatively reaches across the gap between them to touch Tristan’s knee, awaking him. With a daft lover’s smile he says, “let me die.”

The contradiction of their love is fully expressed. Their quotidian life, the material world and everything in it, is nothing but a prison obstructing the union of their hearts and souls. Their love is bigger than the world and everything in it.

“I am Tristan and Isolde,” Tristan says, “and you are Isolde and Tristan.” They mount the precipice and leap into the abyss.

Their music rises to the fevered pitch of physical union without physical union. Continuing to conduct her, Tristan leaps and dances with sheer exuberance while they garland each other with rapturous melody. He is irresistibly virile. She is deliciously feminine, yin to his delirious yang.

Yet they remain chastely physically separate. They don’t embrace, kiss, or roll around on the floor together. Instead, they double over, laughing madly with pure bliss as Brangane screams and they are discovered in flagrante delictodoing nothing but marveling together at their dimensionless love.

I have never been as viscerally moved by this scene as here, under the alchemical spell of a magisterial Barenboim, the sorcerer Tcherniakov, the magnificent Staatskappelle Berlin, and, especially, the incandescently human Schager and Kampe. Together they let us in on what world-destroying, world-creating love feels like.

When Tristan sings “I would gladly leave the life in my body for love,” we feel it. We grasp how being trapped in a body/space/time feels when measured against being see free by limitless love, even if it means dying.

I would be remiss not to acknowledge the extraordinary range, beauty, and energy of Schager’s act 3 Tristan. It was impossible not to feel his unbearable pain at being neither free of the world nor united with Isolde, trapped in a nightmarish limbo.

It was likewise impossible not empathize with faithful Kurwenal, doing everything possible to keep alive a man who wants to die. Like Kurwenal, I was staggered by the enormity of Tristan’s brutally physical despair. In exquisite detail, acted and sung, Schager is overwhelmingly broken, tragic, and transcendent.

“Tristan and Isolde” posits a contradiction between the material law-bound world and a lawless, transcendent love that cannot exist within its limits. Wagner resolves the contradiction musically. Isolde’s rhapsodic liebestod, meltingly tender as realized by Kampe, is only the prelude to the real end, the final, sublimely attenuated resolution of the Tristan chord.

It’s the last thing we hear. It’s the orgasm, disembodied and world-engulfing.

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

-

Topics: daniel barenboim, dmitri tcherniakov, wagner

Call for submissions: parterre box‘s new Talk of the Town

parterre box is launching a new themed regular feature curated by our readers and opera fans across the world! We are asking for your favorite clips, recordings, and anecdotes to get people chatting, listening, and thinking.

parterre box is launching a new themed regular feature curated by our readers and opera fans across the world! We are asking for your favorite clips, recordings, and anecdotes to get people chatting, listening, and thinking.

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments