Franco Faccio (1840-1891) was one of the bright young men of the Scapigliatura movement, in which 19th-century Italian bohemians championed foreign influences and challenged old ways in the homeland’s arts. The second of Faccio’s two operas, Amleto (Hamlet), with libretto by Shakespeare buff and Scapigliatura comrade Arrigo Boito (1842-1918), was a reasonable success at its May 1865 premiere in Genoa.

An account in Movimento read in part: “The public […] rushed in great numbers and with an attitude of one who wishes to judge with circumspection, and, let us also say, with severity. But from expectations of doubt they changed their mind, and after having waited to think about it, a decision was made; they applauded and applauded with spontaneity, with conscience, with enthusiasm.”

Another critic, the Milanese Filippo Filippi, pointedly claimed that “in 40 years, Italy has not seen such a complete opera, such a modern and refined work.”

Such slights were not lost on Italy’s most successful active composer, who had written all but the final four of his 28 operas. Smarting from the failure of the Paris revision of Macbeth the previous month, and noting none-too-coded swipes at him and his immediate predecessors in remarks of the Scapigliatura and their acolytes, Verdi wrote to librettist Francesco Maria Piave: “[I]f Faccio succeeds, I am sincerely happy. Others perhaps will not believe this, but only others. You know me and you know that I either keep quiet or say what I feel.”

Like many people in their twenties, Faccio and Boito ultimately learned that it (any “it”) was not as easy as their elders had made it look. Amleto‘s 1871 revival at La Scala was a disaster, partly owing to a voiceless tenor protagonist, and the composer was so shaken that he withdrew his opera. Amleto would not be performed again in his lifetime or for more than a century thereafter.

Faccio focused on his true calling, conducting, and both he and Boito (who traveled his own rough road with Mefistofele) ended up linked in history with the master they had once challenged. Boito became Verdi’s last and greatest librettist. Faccio conducted the Italian premiere of Aïda, the first performances of the Simon Boccanegra revision and the four-act Don Carlo, and the world premiere of Otello.

Any bore wandering around a lobby during intermission can tell you that Verdi had an unrealized dream to set Lear. Only the bore a cut above will know that he also dreamed of setting Hamlet. In 1850, between Luisa Miller and Stiffelio, he resisted the lure of a distinguished Italian writer and prospective librettist, claiming that for the moment he was aiming lower. “Now, if King Lear is difficult, Hamlet is even more so […] I do not give up all hope, however, that one day I can get together with you and work on this masterpiece of the English theatre.” That day would not come.

Many other composers have taken up the task, but until recently, the only Hamlet opera we were still likely to see—on occasion—was Ambroise Thomas‘s French grand opera, not directly based on Shakespeare. Just this year, Australian composer Brett Dean‘s new Hamlet premiered to acclaim at Glyndebourne. Faccio’s opera was unearthed earlier in the decade, when conductor Anthony Barrese labored over a critical edition that received concert performances in Baltimore and staged ones in Albuquerque, both 2014. Two years later the opera was given at Opera Delaware and at Bregenz.

The Bregenz Festival may be best known worldwide for its operatic spectaculars on the floating stage of Lake Constance, but arguably the more important work is done indoors. The festival’s administrators deserve credit for their attention to the forgotten and the neglected. In the past decade, there have been, among other rarities, Krenek’s seminal twelve-tone opera Karl V (1938) and the belated first staging of Weinberg’s The Passenger (1968), the DVD of which I reviewed for parterre.

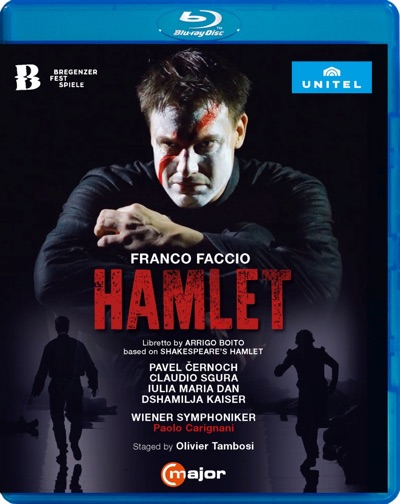

Now, C-major has made available the first DVD/Blu-ray of Faccio’s Amleto, from Bregenz 2016. Although the English title appears on the disc’s packaging, I will use the Italian title and character names for the sake of consistency.

Boito’s libretto is, much as expected, a skillful and linguistically elegant distillation. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and the exile to England are out, and the protagonist’s indecision and doubt feature less than opportunities for temper and brooding that would be attractive to an Italian tenor, but the outline is faithful. The four-act opera runs about as long as the Verdi/Boito Otello.

Denmark’s widowed Queen Gertrude (mezzo) has hastily remarried her brother-in-law, Claudio (baritone). The returning Prince Amleto (tenor) resists entreaties to join the merriment and accept the new order. The dead king’s ghost (bass) appears to Amleto and claims he was poisoned. Amleto pursues vengeance with the aid of friends Marcello (baritone) and Orazio (bass).

Amleto feigns madness and spurns the love of devoted Ofelia (soprano). Amleto arranges a play that closely follows the ghost’s account of regicide/fratricide, and Claudio’s agitated reaction points to his guilt. Amleto cannot bring himself to stab Claudio while the latter is praying, but subsequently kills Ofelia’s father, Polonio (baritone), who is hidden behind a tapestry. The ghost reappears to prevent Amleto for murdering Gertrude.

Ofelia, having lost her father and believing Amleto has abandoned her, goes mad and drowns. Her brother Laerte (tenor) conspires with Claudio to kill Amleto. Amleto easily wins a fencing exhibition with Laerte, but a bloodbath ensues. Gertrude drinks poisoned wine intended for Amleto. Laerte stabs the victorious Amleto in the back. Amleto disarms and fatally wounds Laerte. Laerte confesses the conspiracy and tells Amleto he will soon die of the strike from Laerte’s poisoned blade. Amleto murders Claudio before himself expiring.

“This style smells like mold a mile away! Over time it will bore us,” sings Amleto in the second act. Not so, musically. Faccio’s score is the work of a learned composer, and with a century and a half of hindsight, the familiar registers more strongly than the once-innovative. We hear many reliable tricks of the trade (e.g., a bass’s grave pronouncement getting timp/brass reinforcement on each quarter note), with hints of a distinctive voice that might have emerged had Faccio not abandoned composing. The writing for voices is congenial, the scoring efficient, not with the mastery of late Verdi but beyond most operas of the primo ottocénto.

A short, effective prelude begins in regal sobriety and erupts into storms. The first scene has a patented Italian-opera drinking song, introduced by Claudio and subsequently taken up by Gertrude. It has a great tune, but it comes out hesitantly, in fragments. The movement evokes a party that the hosts are trying to prod to life; though ostensibly under way, it will not get started. The people fooled are the ones who have to be fooled, the courtiers and entertainers. But the sulking Amleto never turns around to see the frowns on the jugglers and the clowns when they all do tricks for him.

There is some young-composer clumsiness—the ending of the first act feels truncated and anticlimactic, as if an Amleto/Marcello/Orazio oath trio is about to break out and does not—but the score gains in force and assurance as it proceeds. The mother/son scene of the third act superbly mingles anger, fear, love, and the recurring figure of Amleto’s mocking notated laughter. The orchestral music of Ofelia’s funeral procession was said to be the score’s most impressive passage at the opera’s premiere in 1865, and it remains so today.

The cast Bregenz assembled is about as good as one could reasonably expect from this festival in a little-known work. This is to say that even without scouring the cemeteries, you will be able to imagine better voices and more interesting performers for some of the roles, but Bregenz would never have been able to get them all of them to sign up for Amleto at the same time.

Fortunately, the casting is strongest at the top. Pavel Cernoch‘s vivid and charismatic Prince Amleto is a ferocious star performance. He has a good deal more vocal presence than others on this recording, in which the orchestra dominates. I had not expected this leonine fullness of timbre from a voice that had sounded light to me in Traviata, Rusalka and The Tsar’s Bride, but not having been in the auditorium in 2016, I will not speculate. What I can say is that he has greater control over the top of his voice than I have noted before.

Cernoch grabs onto this mercurial character and steers through his moods with terrific focus and body control. Everything he does is arresting and meaningful. His acting opposite the father’s ghost turns the bass’s recitation into a duet. At one point, while feigning madness, he simulates bouncing on a horse while crouched on a table. He advances closer to its edge and leaps to stage level without breaking the vocal line.

Bass Gianluca Buratto, who sings the ghost’s two scenes and returns as a priest, makes a rich sound in the middle and can tell a good story. Romanian soprano Iulia Maria Dan creates something less compelling than Ofelia’s music and drama promise. The sound lacks body and comes in and out of focus, with low notes often covered by the orchestra. The acting is standard ingénue. What you are expecting her to do with her face and eyes when Ofelia pleads with Amleto, or loses her reason and wanders around in the bushes, is just what she does. The character lacks specificity, and thus tragic impact.

Olivier Tambosi‘s production cleanly makes Amleto‘s major points without finding much around them. Davy Cunningham‘s lighting creates some beautiful effects, and there are attractive stage pictures. The best of these are the ghost’s two appearances out of blinding white light, suggesting the afterlife as a photo-negative sea, and the candlelit procession for dead Ofelia. The final scene has a well-choreographed duel for the two tenors.

There is more ambiguity in these characters, especially Gertrude and Claudio, than there is in what Tambosi has asked of the singers. He has them playing what is on the page, the lines and the surface attitudes, not much in the margins.

Should neutrality be a goal, even when a new work is being presented? If so, what if only the music is really “new,” the drama very familiar? Time and space preclude the delving the subject deserves, but I feel that this production would have received more criticism if Amleto had been better known. Ms. Kaiser is let down by the staging of Gertrude’s dramatic aria, which has her singing dynamic music while sitting on the bed like a lump.

For most of the aria, the in-house audience would only have seen her in right profile. Ms. Dan performs Ofelia’s mad scene amid an acre of fake foliage. A piece gets caught on her gown and she drags it with her, becoming “sane” for a second to disengage it.

Conductor Paolo Carignani leads the Vienna Symphony Orchestra and Prague Philharmonic Choir through an account that has punchy impact in the genre bits, but broadens out for sensitively guided lyric episodes.

D.C. doyenne Anne Midgette reviewed Amleto in its Baltimore and Wilmington outings (neither with Tambosi’s production or this cast), and while she was enthusiastic both times, she decided it was “not a forgotten masterpiece.” She is probably right. Amleto sounds to me like the work of a composer who eventually may have written great operas, but decided to contribute to music in another way.

However, sometimes our ideas about “masterpieces” are influenced by what interpreters bring to them. There are the pages, and there is what others bring to those pages. A masterpiece is something like sedimentary rock. (Sometimes what the generations have added or taken away from a masterpiece arguably has hurt it, e.g., Trovatore.) We cannot look back over 150 years and talk of the Amletos of Caruso, Zanelli, Bergonzi and Domingo. We cannot talk of the great Amleto production of Visconti or Strehler or (yet, anyway) of Carsen or Herheim.

More than 150 years after those kids Faccio and Boito got their show put on in Genoa, we have a big, inviting canvas that is largely blank. The Brengenz DVD/Blu-ray, combining the great, the good and the adequate, demonstrates that there is enough here to interest singers, conductors, directors and audiences. This seems more likely to happen than it has at any time since the Scala debacle of 1871, and there is some excitement about this. Va, Amleto.

Comments