Not a great deal happens in I due Foscari. Characters anticipate events with dread, react to them with anger or resignation. Some of those events occur offstage. This short opera of mood and color is admired for its “experimental” nature but is of greater interest for its consolidation and refinement of musical techniques. Both the opera and Byron’s source play of 15th-century intrigue, The Two Foscari, place us in the shadowy, menacing Venice explored in many dramatic works through the centuries.

Jacopo Foscari (tenor), last surviving son of Doge Francesco Foscari (baritone), stands accused of treason and murder in events prior to the opera’s timeframe. Jacopo’s wife, Lucrezia (soprano), protests her husband’s innocence and pleads with her father-in-law to intercede. Torn between duty and paternal love, Francesco is compelled to uphold the verdict of the fearsome Council of Ten. Jacopo is exonerated too late and dies aboard the ship carrying him to exile. Old Francesco, now forced to abdicate his throne, follows his son in death.

No one should look to Verdi (or to Byron) for history, and we need not trouble ourselves here with the deeds of the historical Foscari. It is for chroniclers to record facts, and for artists to provide a different kind of truth. Verdi was 31 when he wrote Foscari; one can only marvel at the sympathy and understanding with which he treats the elderly Doge. In Lucrezia’s music he captures the heroine’s spirit as well as her anxiety. This is a woman of strong will and certainty of her rightness, but also awareness of her powerlessness. Jacopo’s music is heartbreaking. He could be any political prisoner of any era, with everything stacked against him, bidding goodbye to country, to family (he too is a father), to life. As in so much of his work, Verdi gives souls to these characters.

The opera was only a modest success, and the composer, always alert to the public’s judgments, would dismiss it in later years (“[I]f you’re not careful, you end up with a deadly bore – as for instance I due Foscari, which has too unvarying a color from beginning to end”). Nevertheless, the opera is delicate and full of pathos, in my judgment the best score Verdi had completed to that point. Julian Budden astutely linked pairs of Verdi operas separated by nine years: surging vitality and passion (Ernani, Il trovatore) followed by intimacy and melancholy (I due Foscari, La traviata).

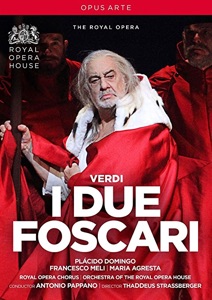

Antonio Pappano‘s conducting of the Royal Opera House’s orchestra has case-making zeal and sharp definition about it. In an extra feature on the DVD, Pappano plays some of the opera’s themes on the piano, talks about their meaning, and points out similarities to later Verdi. He comes close to losing his composure at one point, so moving are these phrases he has heard many times. His love for the music shows in his conducting, which (along with the choral singing under Renato Balsadonna) is the performance’s strongest suit. There are many beguiling solo contributions from the ROH players. The weightiness and tenderness of Foscari are conveyed in good balance. There is heavy underlining here and there, but if the maestro errs on the side of momentousness, it is surely because he wants I due Foscari to impress an audience coming new to it as the great music he believes it to be. There are worse sins.

American director Thaddeus Strassberger was about 35 when he devised this stage production. It is possible that someday he will look back on it ruefully. For now, the ruing falls to me. My suspicion is that Strassberger thought the solution to an opera in which not much happens was to crowd the perimeter with as much as possible, to add a lot of visual stimulation, rather than to come in close on the emotions at the core. This “spectacular” I due Foscari parades before us one miscalculation after another.

Verdi experimented here with the device of the leitmotif. He was employing a technique new to him in a somewhat naïve way, and his leitmotifs for the major characters and for the Council are static in form (think of Nabucco’s jaunty banda march, multiplied). Every time we hear the leitmotif of Lucrezia, for example, she makes an entrance.

The conductor knew this was entrance music; the cast knew this was entrance music; probably the small children playing the Doge’s grandsons knew this was entrance music. If Strassberger did not know, someone must have told him. But he has the soprano on the sidelines for the entire final scene, wearing Angela Gheorghiu‘s wig and nightgown from Act Three of the Eyre Traviata (probably not, but they could be), carrying on wordlessly in a banal mad scene. Lucrezia’s now-familiar leitmotif plays in the orchestra with no entrance, a breach with what was done in all the earlier scenes. Now it means not that she is entering, but that finally there is a point to her being there. She can sing, and we can stop wishing she were offstage.

Jacopo sings his cavatina in a suspended cage while superfluous Council business goes on at ground level. A Council/Junta chorus is staged with all the robed villains eating an elegant dinner from a table that is slowly gliding toward stage right, while Jacopo is taking communion and scuffling with his captors in the foreground. There is a gantry for people to wander atop. Hunky prisoners in loincloths are suspended from the gantry and tortured with fire, pulling focus from Jacopo. A female super gets sexually assaulted, as female supers do. The carnival scene in the third act features acrobats and fire twirlers. Doge Foscari’s chief antagonist, Loredano, takes away a shirtless acrobat’s girlfriend and assigns her to a crony.

This busy staging in colorful historical dress is just a horse and mule away from evoking late Franco Zeffirelli, although the Zeff would have had the rubble swept up. The clutter would count against it less if the whole thing were not so emotionally inert. In the prison duet, Lucrezia wipes blood from her battered husband’s face, realizes it is time for her to interject a line, turns and faces the audience, and then returns to wiping blood. Perhaps the falseness there is half on the singer, but other transgressions are all on the director. The winner of a contest might have looked at this libretto, heard this music, and come up with better blocking for the farewells of Lucrezia and Jacopo. For no good reason, they are singing at each other from opposite sides of the stage.

Having Lucrezia go mad at the end may be an interesting choice or it may be a terrible choice, and that is a debate the audience can have on the way out. However, it is a big choice, and if you are going to make it, you have to commit. You have to direct a progression throughout the opera that makes madness seem at least plausible, if not inevitable. Here, it comes out of nowhere. We see Lucrezia drowning her son in a puddle at the final curtain (none of the dozens of people onstage are pulling her off), and what is there to say but “Well…that happened”? I am being unfair. Right before she went mad, she had a smudge on her forehead, and her wig was messy.

Some cast of past or present might have been able to battle the chaos to a draw and win the day for music, but this cast is not the one. Tenor Francesco Meli makes the best showing. In my experience, he often has been a slow starter, and that is the case here. He sounds tight and not properly warmed up for “Dal più remoto esilio” and the cabaletta. His physical expression there is cheated by the staging – even with the cameras, we cannot see him well through his cage. He finds another gear in the duet “No, non morrai” and does reasonably attractive singing in the balance, but he is a serviceable, generic hero rather than a poetic one.

Maria Agresta is a singer of fine qualities, but Lucrezia is not a good role for her bright lyric soprano, at least not in 2014. It is rather like Mirella Freni singing Aïda. You think well of her, you grant style points, and maybe you are grateful not to have a lesser soprano with similar equipment, but it never seems a good idea in itself. There is no ease in the singing, nor illusion of ease, only technique creating the means for a singer to punch above her weight and get through. Agresta cannot be said to compensate dramatically, her default temperament being a milder one than this fiery character cries out for. She has several costume changes, and designer Mattie Ullrich‘s elaborate gowns and hats wear her.

Maurizio Muraro, usually a performer of some personality, goes blank as Loredano. It is not a well-developed role, and there is no shame in not making more of it, but I have never seen Muraro walk through anything as he does here.

Kicking off the last act with projected Byron text reading “You have no right to reproach my length of days” was of questionable wisdom when the star was to be Plácido Domingo. At his present age, the tenor-turned-baritone is less consistent, both between performances and within them. Here, I find him most effective in recitative. He shows his mastery in the projection of words, and he has absorbed much about the composer’s style. Arias and duets serve notice that the breath line is shortening, the emission loosening, the tone fading. He is managing carefully, sometimes sounding good for his age, other times just sounding his age. If one can set aside that he is not a baritone but an aged tenor, and many will not, Francesco Foscari works better for him than some other recent roles have.

I remember a Met broadcast in 2005 in which Domingo sang a Siegmund that would have been the envy of a heldentenor 25 years younger. After his character was dispatched by Hunding, Domingo went directly to a singers’ round table, and there I first heard him speak of a plan to try Simon Boccanegra before retiring. Eleven years later, here we are. I have read that this series of Foscaris sold well. Maybe London audiences relished an opportunity to be in the presence of a legend. I do not believe they heard great singing, or saw more than a boilerplate Domingo performance in the tragic mode.

Bruson’s best singing was behind him at that time too, yet there is nothing casual about what he does, nothing phony about the tears in his eyes or the ache in his throat when he concludes “Questa dunque è l’iniqua mercede.” He persuades us that Francesco Foscari’s suffering means something to him, and so it may to us. Surprisingly, although he was decades younger than Domingo at the time of their respective filmed Foscaris, it is he who more convincingly plays advanced age and an awareness of death’s approach.

This lesser-known Verdi, not a masterpiece but an opera of no small intrinsic worth, got a chance in this decade and was badly served, and such is always unfortunate. But Verdi survives bad productions and good ones alike. You are reading a piece in 2016 about an opera that is not Verdi’s best, his tenth-best, or even his best about an unhappy Doge with parental concerns, and the opera is still worth hearing and studying. Verdi will outlast the London critics who said it was a rum do that this cod old piece was got out; he will outlast Strassberger, Pappano and even Domingo; he will outlast you and me.

The somber beauty of I due Foscari is there to hear in the recordings conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini and Lamberto Gardelli, and, mostly for Bruson’s performance, in the Scala DVD conducted by Gianandrea Gavazzeni. That is the consolation, even the triumph. The provider endureth.

Comments