, while the uncropped photo of countertenor Xavier Sabata (above) is even more disturbing, featuring his raised fist and forearm tightly wrapped in a leather belt.

Over the past weeks new Messiahs by Le Concert d’Astrée and Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society

have been released, but why don’t those who listen again and again to that 18th century masterpiece consider instead this Tamerlano, just one of a recent overflowing of Handel recordings. If this new Naïve CD doesn’t fully achieve that image’s powerful effect, it is still a worthy rendition of one of Handel’s greatest operas, written during that astonishing 18-month burst of creativity that also produced Giulio Cesare and Rodelinda.

Tamerlano has never achieved the popularity of the other two, perhaps because it is among the composer’s darkest works. After the Tartar victory over the Ottomans, the defeated Bajazet and his daughter Asteria are imprisoned. In love with the noble Greek prince Andronico, she is pursued by their captor Tamerlano. After his plot to poison the emperor is discovered, the proud Bajazet commits suicide causing the villain to allow Asteria to reunite with her lover. Despite that welcome news, the soprano faints leaving the final coro to three altos and a bass, Handel’s most bitterly ironic “happy ending.”

Leading his period orchestra Il Pomo d’Oro in an edition modeled after Handel’s 1731 revision, Riccardo Minasi occasionally reveals his relative inexperience as an opera conductor: while individual numbers often prove bracing or moving, the whole enterprise fails to cohere. Although they may lack Minasi’s more glamorous cast, earlier recordings by John Eliot Gardiner and George Petrou

prove more affecting.

Towering over the new version is John Mark Ainsley’s Bajazet, a fine portrayal that admirers of this elegant British Handelian have hoped for. The veteran’s dulcet tenor is still admirably steady and as always he negotiates the florid writing with grace. More importantly he skillfully delineates the deposed leader’s humiliation in the remarkable sequence of accompagnatos and ariosos that culminate in his suicide.

As his daughter, Karina Gauvin makes a more equivocal impression. With Sandrine Piau, Gauvin is probably today’s leading Handel soprano; however, as the years pass she has evolved into quite a grand singer, a manner not well suited to the young and innocent Asteria. While she rises admirably to the demands of the drama of act III, particularly in her wrenching “Cor di padre,” Gauvin seems miscast.

The sweetly suave Sabata also may strike some as questionable casting for the brutal title role, however, he often successfully subverts the listener’s expectations by portraying a more subtle, insinuating villain than usual, although he’s clearly challenged by the fiendishly demanding “A dispetto.” In the important role of Asteria’s lover Andronico (written for Senesino), Max Emanauel Cencic once again proves more an appealing and fluent vocalist than a compelling singing actor. While his command of the music is admirable, one never feels the character’s conflicting allegiances, especially in the grand scena that ends Act I.

As the discarded Irene, Ruxandra Donose sings well but I again dislike her low, often rough-sounding mezzo. Inexplicably she’s asked to speak rather than sing some of her arietta “No, che sei tanto costante,” but one is happy to hear her “Par che mi nasca in seno” in its later version rewritten to include a pair of clarinets which rarely appeared in orchestras then. Pavel Kudinov too gains an alternative aria, the dazzling bass showpiece “Nel mondo e nell’abisso,” which he dispatches with flair.

Orlando, a striking work of chivalry, thwarted love and madness, followed a decade later and is one of the three operas Handel based on Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso; not one but two recordings of it have recently been released. Once considered one of the best conductors of this repertoire, former countertenor René Jacobs has grown increasingly willful and mannered, and his version on Archiv is a mess

.

His habit of tinkering with the orchestration has become downright perverse: he includes an organ as a continuo instrument throughout and recorders routinely appear even though Handel only specified their use once or twice. Although the Belgian period orchestra B’rock plays well for him, his tempi are extremely fast throughout (perhaps to squeeze the opera onto just 2 CDs) except when he unexpectedly brings everything to a screeching halt for decidedly odd cadenzas.

His unsatisfying cast includes Konstantin Wolff as an inelegant, rusty-sounding Zoroastro and Sunhae Im as a hard-driven, soubrettish Dorinda. While Kristina Hammarström shines as a plangent Medoro, her Angelica, Sophie Karthaüser, is meek and wan. Jacobs’s favorite countertenor Bejun Mehtais in characteristic form as the anti-hero. Ever since he burst onto the scene in Partenope at the New York City Opera in 1998, I have been disturbed by the wiry unsteadiness I hear in his singing. The passing years have only increased that flaw, and some of this Orlando (recorded at a live performance) is painful to listen to. And, yet, having seen Mehta twice in the role—at New York City Opera and at Covent Garden—I am not surprised that he is able to exploit these whining vocal eccentricities, combined with his diffident manner, to create an oddly touching madman.

recording of Orlando could scarcely be more different. Alexander Weimann and the Pacific Baroque Orchestra are a model of taste and rectitude, reveling in the score’s many pastoral pages, while the cast is, in almost every case, superior to Jacobs’s. Gauvin’s grand manner, while wrong for Asteria, sounds perfect for Angelica and she’s on her best vocal form, sounding free and golden.

As fine as Hammarström is as Medoro, the under-rated Allyson McHardy is as good or better, her rich, even mezzo excelling in a melting “Verdi allori.” And Amanda Forsythe is not only true to Dorinda’s sparkling side but also to her heart-breaking one, particularly in her ravishing performance of the magnificent “Se mi rivolgo al prato.”

Countertenor Owen Willetts lacks the flamboyant manner of Mehta as Orlando but his singing is much more pleasing even if it perhaps is a bit too reticent. A decade ago the experienced Handel bass Nathan Berg might have been an ideal Zoroastro, but this recording finds his voice is rough shape and his once-fluent coloratura has grown a bit unwieldy.

It’s difficult to believe that there are now three recordings of Faramondo, one of four operas from the late 1730s long considered to be lost causes. While its libretto is one of Handel’s most impenetrable, the opera is full of fresh, dramatic music that repays attention. Coming just five years after an impressive version on Virgin Classics featuring Cencic, Sabata, Karthaüer and Philippe Jaroussky, the Göttingen Handel Festival has now issued a new

Faramondo on Accent.

After having participated in a series of recordings on Harmonia Mundi with the festival’s previous music director Nicholas McGegan, this is the second in a new series of live recordings made at the festival conducted by Laurence Cummings, its current director— I have not heard the first

, Siroe.

Despite some bothersome stage noise, this new Faramondo nearly equals that earlier fine studio effort. Cummings draws stylish playing from his period orchestra and the youthful cast in nearly every instance is more than equal to its challenging roles. Countertenors Maarten Engeltjes and Christopher Lowrey shine as Adolfo and Gernando if perhaps without the polish and star power of their better-known colleagues on Virgin. Soprano Anna Devin who sparkled in the small role of Oberto in the recent performance of Alcina at Carnegie Hall continues to show promise here as a radiant Clotilde full of fire.

But in the title role created by the famous castrato Caffarelli, the young American mezzo Emily Fons gives a glamorous performance of a high international standard. Reminding me more than once of a young Joyce DiDonato, Fons displays an impressive command of Handel style singing with richness and flair and her coloratura is especially dazzling.

The zeal of singers to record all- or mostly- Handel recitals continues. Having made her first Handel CD in 1991, French contralto Nathalie Stutzmann has returned with an unconventional program entitled “Heroes from the Shadows” dedicated

to arias sung by secondary characters.

It’s an interesting group of lesser-known pieces and a worthy companion to Sabata’s similarly themed “Bad Guys” CD from a year or so ago. While one understands her desire to sing the sublime “Son qual stanco Pellegrino” from Arianna in Creta, the aria is written for soprano and becomes nearly unrecognizable in Stutzmann’s downward transposition.

Where she collaborated on that first disk with Roy Goodman and The Hanover Band, this time she conducts her own orchestra Orfeo 55. Favoring brisk tempi and clear textures, she secures lively playing from her young band. While Stutzmann has remained almost exclusively a concert singer, each selection here is nicely characterized and despite having been before the public for many years now, her earthy deep alto voice remains in good shape. Her coloratura proves surprisingly nimble in a ferociously fast “Sarò qual vento” from Alessandro.

Jaroussky makes a guest appearance in the famed Cornelia-Sesto duet from Giulio Cesare where his high feminine voice blends gorgeously with Stutzmann’s more masculine one. Although Stutzmann has never been a favorite of mine, this CD shows her admirably continuing to explore new horizons.

Would that Alice Coote’s new Handel program

on Hyperion proved as rewarding. Working with her frequent colleague Harry Bicket leading a surprisingly scrawny-sounding English Concert, Coote performs a program consisting of highlights from her stage roles: Ruggiero (Alcina) Ariodante, Dejanira (Hercules) and Sesto (Giulio Cesare) with an arioso from Radamisto thrown in. Everything is cautiously sung to avoid putting any undue pressure on the voice. The florid music is neatly dispatched but without any particular fire and flair; at least she avoids the train-wreck “Sta nell’ircana” became at the recent Carnegie Hall Alcina.

Some pieces are done very slowly—for instance Coote’s “Scherza infida” takes 11:41 whereas the famous 1978 Janet Baker recording just 8:11; her “Verdi prati” lasts nearly a minute longer than Susan Graham’s or Maite Beaumont’s. Repeated listenings have convinced me that the disk is not the grave disappointment it seemed at first but it remains a bore—careful, unimaginative readings of popular arias available elsewhere in better versions.

For well over a decade, American countertenor Lawrence Zazzo has been a stalwart of many important stage productions and recordings of Handel operas without capturing the public imagination in the way, say, David Daniels or Andres Scholl did or Jaroussky or Cencic do now. He remains a consistently valuable singer as he demonstrates on his lovely recent recital

“A Royal Trio” which features music by Handel along with his contemporaries Ariosti and Bononcini, accompanied by David Bates and La Nuova Musica.

It’s a pleasure to hear Zazzo despite his less-than-glamorous timbre still singing so well these days. The happily-chosen Handel selections mix the familiar (Giulio Cesare and Rodelinda) with rarities from Ottone and Admeto. But perhaps of more interest are those by the two other composers who shared the stage at the Royal Academy. As Zazzo excels more at pathetic arias than heroic ones, he is at his best in the mournful “Con stanco Pellegrino” (with its splendid cello obbligato) from Bononcini’s Crispo and “Voi d’un figlio tanto misero” from Ariosti’s Coriolano. It’s also good to hear Bates and his orchestra in such fine form particularly after their lackluster debut with Il Pastor fido several years ago.

Happily Zazzo will be making a rare New York City appearance this spring as Athamas when Handel’s Semele is staged at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in early March.

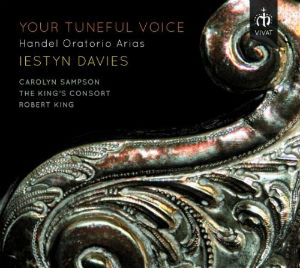

The essential

Handel CD of 2014 however arrives from another countertenor: Iestyn Davies and “Your Tuneful Voice” on the Vivat label. Although I haven’t always been this British singer’s biggest fan particularly in Italian music, the miscellany of music from Handel’s English oratorios presented here shows him to be unbeatable in this music. After the poor showing by The English Concert on the Coote CD, it’s a thrill to re-encounter Robert King, hero of so many fine Handel recordings on Hyperion, again leading his King’s Consort in absolutely top form. Together Davies and King make a splendid team.

Davies conjures here the best aspects of the British countertenor tradition—also heard in someone like Paul Esswood–where a lovely pure tone, impeccable diction and an effortless command of Handel style thrive but without the dreaded “cathedral countertenor” hootiness that affects so many (this phenomenon mars, for example, Willetts’ Orlando).

Like Zazzo, Davies handles florid music well—Esther’s “How can I stay when love invites” just bubbles with charm, but he really shines in slower music, particularly in the exquisite “Mortals think that Time is sleeping” with its cooing recorders from The Triumph of Time and Truth, a rare late work which by the way received a fine recording by Richard Neville-Towle and Ludus Baroque this year.

A pair of rapt duets from Esther and Solomon with the crystalline soprano of Carolyn Sampson is also included and the intertwining of their voices is absolutely seraphic. A wonderful adjunct to this Handel gem is Davies’s delicious recent Purcell and Blow collection “Arise my Muse” on the Wigmore Hall Live label.

That Davies will appear in the ideal role of David in Barrie Kosky’s new production of Saul at next summer’s Glyndebourne Festival is very happy Handel news indeed.

Comments