No, older Venice than that. Older than Henry James. Older than opera. 552 a.d., no less when (on the Italian mainland), as you recall, the Byzantines had whipped the semi-barbaric and Germanic Ostrogoths only to bring the extremely barbaric and Germanic Lombards down upon themselves as a result. Out in the Adriatic lagoon, refugees ignored the byzantine infighting and started a city all by themselves. (It’s called Venice.)

This was a fashionable historic locale for artistic retrospection round about 1900: in the darkness, the glittering and basic emotions of our distant ancestors, glamorous with heavy gems and golden slather. Today, one Yeats poem and the paintings of Gustav Klimt are pretty much the only survivors.

Teatro Grattacielo, high exalted knightly keeper of the Verismo flame, proposed to revive Montemezzi’s La Nave last Monday at Rose Hall on Columbus Circle. It should not surprise anyone that this schedule aroused the weather gods to inflict New York’s worst case of Acqua Alta since the Algonkian administration. None of this is astonishing. What does astonish is that Grattacielo (which means “skyscraper”) survived Sandy and got its act together by Wednesday, Halloween, and that the performance came off with only one singer replaced at the last minute.

The opera itself did not astonish, but it made an enjoyable surprise, far more thrilling and elaborate than Montemezzi’s only hit, L’Amore dei tre re. La Nave‘s rarity on the stages of the world may be due to the size of the thing. The opera calls for a powerhouse cast, enormous chorus, corps de ballet, vast and colorful sets and an enormous orchestra.

L’Amore dei tre re is much easier on the singers, calls for hardly any chorus and just a couple of basic, barbaric sets, being also set in the Italian Dark Ages. The only difficulty is finding a basso capable of lifting the soprano (after strangling her) and hauling her off stage. If she is larger than Lucrezia Bori, this can be a problem. Beverly Sills said whenever she saw Fernando Corena in later years, he would moan and bend over as if his back had never recovered from the ordeal.

La Nave is based on one of the historical farragoes concocted by Gabriele d’Annunzio after overexposure to Friedrich Nietszche (and Wagner). Basiola Faledro, almost the only woman in the cast, belongs to an aristocratic family from Aquileia, which was the chief Roman port of the upper Adriatic until one day Attila the Hun showed up.

The town was never the same. Its ruins had just been excavated in 1909 when d’Annunzio wrote his play, and some of the Venetian hostility in the text may be due to the fact that the old city was still on the Austrian side of the border. Basiola’s father and four brothers, suspected of being in Byzantine pay, have just been blinded at curtain rise. Also the bishop has just died.

The fickle Venetian mob acclaim the family’s rival, Marco Gràtico, as the new Tribune (no doges yet), while his brother Sergio (the thumbless one — don’t ask, we are never told) is the new Bishop. The brothers will now run the whole show.

But they have reckoned without Basiola, who seduces both brothers with her sexy dancing in order to get them to fight each other to the death. The bishop is killed, but the vengeful Tribune Marco, regretting his lust for Basiola (who suggested he run for emperor), condemns her to death.

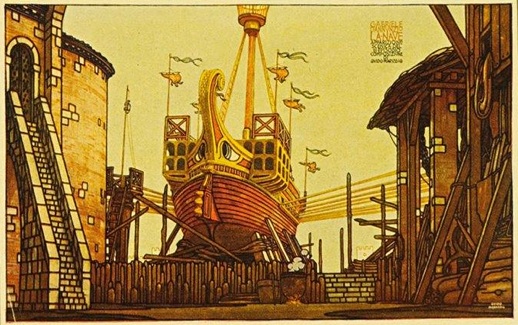

She begs that her death be “a beautiful one,” and he obliges by nailing her to the prow of his ship (La Nave), named Totus Mundus (The Whole World), and sails out to conquer the Mediterranean. Soon after the opera’s premiere, d’Annunzio took ship and made himself the world’s first fascist dictator — seizing the city of Fiume when the Versailles Peace Conference awarded it to Yugoslavia.

It’s obvious d’Annunzio knew Wilde’s Salome very well, and he certainly knew Tristan und Isolde and probably Reyer’s Salammbo. What seems also to be clear is that Montemezzi the composer wisely ignored those far too seductive inspirations. His score, while grounded in Wagnerian motif and method, uses a thoroughly Italian style of melody and orchestration. The horns do not cover the bass; they are illustrative trumpets for heraldic announcements and fight scenes.

The erotic music is not psychologically appalling — it is open in its yearning appeal. The music of this brutal story and its several barbarous scenes is refreshingly delicate, individual in the manner of Respighi’s La Fiamma (more Verismo Byzantinerei), and the instrumental effects are often original and always varied, moving from one group to another as swiftly and picturesquely as the plot.

And how many other operatic heroines seize a bow and arrows and slay an entire ditch full of prisoners one by one, saving the prettiest for last, just to express her ill temper? (And how many sopranos can you picture bringing it off?)

It is the manner of singing called for that assigns La Nave firmly to its Verismo era: All these singers declaim as if they were on d’Annunzian soapboxes; there is very little melody or lyric appeal in their most intimate utterances, though to be fair they are usually denouncing each other for one thing or another.

But these aren’t people you want to get to know, people who express emotion in song. It’s all speechifying, cold-hearted even when impassioned. Montemezzi’s lyricism is confined to the orchestral accompaniment instead. La Nave is more spectacle than story. Great fun to hear it (after two days’ da tempeste il legno infranto), but not a candidate for regular rep.

Teatro Grattacielo always digs up amazing singers to perform their amazing scores. Tiffany Abban, making her New York debut, has a full-sized, well-developed, beautifully supported spinto of womanly color and Verdian weight. She can ride over an orchestra or sing sweetly and softly, and the sound never becomes harsh when weight is brought to bear. She seemed a little tired at the end of Act II (hardly a surprise!) but she rallied for the spectacular conclusion.

This is a voice ready to take on the great mid-Verdi and late-Puccini roles that have long lacked proper presentation, and I look forward to seeing what she can do with them on stage. She has a sturdy figure but she is tall and can carry it, and she sings as if she meant what the words convey.

Robert Brubaker, a better-known quantity, did some startling and thrilling things with the role of Marco Gràtico, especially in the high-lying area where most of the part seems to sit. A bit of cracking by Act III was no surprise and barely a distraction from a fine performance.

Grattacielo veteran Daniel Ihn-Kyu Lee sang the episcopal brother well, and small but distinctive roles were ably handled by Ashraf Sewailam (as Basilia’s blind father), Kirk Dougherty as a stonecutter with an edge to his tongue, Rod Gomez as a helmsman and “A Voice” by Suzanne Stadler, who in one line managed to make everyone sit up and wipe their ears. A future Straussian?

The Teatro Grattacielo’s Men’s Chorus had plenty to do and did it capably, assisted by the Dessoff Symphonic Choir. Israel Gursky, another New York debutante, led the company orchestra and all properties to an exceptionally lively and convincing performance of a work that seemed to delight all palates present. Even allowing for our natural pleasure in a company that had pulled together so fine a performance in our beleaguered city, there was a wide appreciation of so attractive, unsuspected a score.

Comments