When I was a kid growing up in Paris, there was a weekly TV broadcast of a theater play called Au Théatre Ce Soir that I loved. But that my father would rarely let me watch this show, because the plays were all were silly comedies, usually badly acted and filmed without any creativity or originality. Basically, it reflected rather poorly on The Theater.

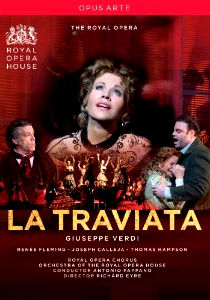

As I was watching this newly released DVD of La traviata filmed at the Royal Opera House in a Richard Eyre production, with Renée Fleming and Joseph Calleja, I could not help but think about those old French TV broadcasts.

It starts well enough, and if nothing else, this DVD soundtrack of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House conducted by Antonio Pappano reminded me how beautiful and touching and powerful Verdi’s score is. With the first few notes of the overture over the opening credits, I thought I was in for a treat: still photographs of a young girl, badly dressed, lower class, are inserted among close-ups of Violetta (Ms. Fleming) bathed in a blue light, seemingly contemplating both her past and her future.

That was probably the most creative moment of the whole film.

As the curtain opens and the action of Act I begins, what strikes the viewer is how small the stage seems as used by Eyre: the set appears crammed, overcrowded with Violetta’s guests, confusing, with no depth. The impression remains throughout the film, with a similar effect in the ball scene of Act II, but also in the “at home” scene of that act, where the back of the stage is lined with a “house” backdrop, and all the action takes place near the orchestra pit. Only in the last act does the stage seem to open up and provide some depths, possibly as a sign of Violetta’s imminent liberation from the sufferings of her existence.

This decision of setting the action within obstructive sets and under dominant monochromatic lighting (red for the crowd scenes, blue for the last act, natural light only for Act II, scene 1) probably made sense for a live performance and for the audience of an opera house. But, because film automatically tends to flatten everything, what comes through in this film is essentially a lack of depth and dimension, and the limitations of the action and characters as fully developed entities. So while Pappano’s conducting brings out the beauty of the score, the film of Eyre’s staging emphasizes the shortcomings of the work, the over-simplifying and one-dimensionality of the characters’ motivations and of the dramatic structure.

This could have easily been remedied with some creative and original camera works, shots or editing. If I look back at the last few filmed operas I have seen (by “filmed opera” I mean the film of a staged opera, as opposed to an “opera film,” which is is a film made from an opera, such as Joseph Losey‘s Don Giovanni), and though filmed at different times and in different cities—from Soviet Russia to the Met in 2010—and of varied quality, all had at least one element, one attempt to use film techniques creatively and inventively to not only put the stage work under the best light, and sometimes offer a new insight onto the opera itself, but also to draw the audience fully into the work. Film, the moving image, the thoughtful use of varied shots and editing techniques has this uncanny ability to capture the imagination and the full fledged attention of its viewers.

Unfortunately this film of La traviata, directed by Rhodri Huw and assembled from the recordings of two separate performances (on 27 and 30 June 2009, an information only available on the last page of the booklet) makes no such attempt to draw the audience in. It is a very pedestrian film, to which little thought seem to have been given, a simple recording and broadcast of an event, without any point of view, any fresh outlook or guts, and so lacking in depth and originality.

Of course it does not help when you bring together one of the most awkward castings I have seen. Violetta, as pictured by Alexandre Dumas fils’s play and Francesco Maria Piave’s libretto is a young thing, not older than 25, who acts her age (and her social position) as a coquette in Act I, before evolving through her love for Alfredo and her self-sacrifice into a saint and a martyr. Watching Ms. Fleming playing coquette in Act I and prancing around the stage under the drooling gaze of Mr. Calleja (pre-makeover surely, since this can’t be the same man I saw in Lucia this season at the Met) was not only awkward but disturbing. It reminded me of Claire Bloom in her fifties playing the ingénue wife in the film A Doll’s House when she acts like a little squirrel to seduce her husband—An image that to this day still makes me nauseous.

Close-ups do not lie. And though I do not find it odd to watch a stage performance by a singer who may not fit perfectly his or her character because of age, ethnicity, body type, etc, on film the inadequacy resulting from miscasting cannot be avoided. Film has this power to enhance the focus of the viewer on every little details that is offered to the eye: a facial expression, the blink of an eye, the movement of a finger. As viewers of the small or the big screen, we are avidly desperate to find meaning into each frame.

And what we get from Ms. Fleming’s acting is at best uncomfortable, at worse unwatchable—although she does somehow redeem herself in the last act and her dying scene, where she appears all disheveled and wretched. Her voice, though a bit mature for the part, is rather enjoyable, once she gets past Act I, where Pappano obviously has to hold back the orchestra and the tempo to allow her to get through her first aria and the cadenza. Mr. Calleja on the other hand is in perfect command of his instrument and would have made the perfect Alfredo if it had been a CD recording. Thomas Hampson as Germont is the most satisfying principal, both vocally and as an actor.

With all the many available filmed versions of La traviata on DVD (a search on Amazon brings up over a dozen, including the same Eyre production in the same house some years back with Angela Gheorghiu and Sir Georg Solti conducting, and another production with Ms. Fleming at the Los Angeles Opera), one can wonder why the Royal Opera House has felt that this film was worth a DVD release. As the market of filmed operas develops through live transmissions and DVDs, it is to be hoped that opera houses will come to realize the full extent of the power and the opportunities that the medium of film offers, and make better use of it.

Comments