Although Walter Braunfels was among those German composers whose music was banned in their home country after 1933, and whose political rehabilitiation in 1945 was not accompanied by a commensurate revival of his music, his 1920 opera Die Vögel should need no special pleading on musical or dramatic grounds. Though Braunfels is traditionally described as a “conservative” composer in comparison with his near-contemporaries Berg and Hindemith, 21st-century ears are more likely to hear his music, at least in this opera, as stylistically midway between Wagner and Strauss, and suffering only slightly in comparison with those better-known composers.

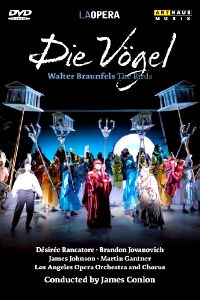

His treatment by the Nazis—he was half-Jewish—resulted in both a ban on his works and his removal as a director of the conservatory in Cologne, but rather than emigrating he went into internal exile at Lake Constance, protected by his voluntary isolation. In the 1920s, however, Braunfels was, with Schreker and Strauss, among Germany’s most popular operatic composers, and despite conductor James Conlon’s admirable efforts to revive music banned by the Third Reich, it is in light of Braunfel’s earlier success that the Los Angeles’ 2009 production of Die Vögel (Arthaus DVD AHM 101529) should be assessed.

Though based on Aristophanes’s Ornithes, Braunfels’s libretto departs radically from its source in ways that transform the Greek political comedy into an allegorical fable deeply indebted, as Conlon observes in the booklet essay, to Schikanader’s Zauberflöte. The buffo Ratefreund (“Faithful Friend,” James Johnson), a reïmagined Papageno, rejects human society and convinces the world’s birds to build a city in the sky, including a wall to block passage of the smoke from mankind’s sacrifices to the gods in heaven, making the birds rulers of the universe.

Ratefreund himself is seen to more or less usurp the Hoopoe (Martin Gantner) as King of the Birds. This much unfolds in Act I, hewing closely to Aristophanes. In fact, viewers expecting an analogue to Mozart’s opera may be a bit bewildered as Ratefreund takes charge and the Tamino-esque Hoffegut (“Good Hope,” Brandon Jovanovich) does little but stand around.

Hoffegut comes into focus somewhat abruptly in Act II, which opens with an inter-species love scene (invented by Braunfels) for Hoffegut and the Nightingale (Désirée Rancatore), whose function as Hoffegut’s “Pamina” is belied by her voice and costume, which are pure Königin der Nacht. That their “love” is presented in purely allegorical terms—in which the Nightingale finally grants Hoffegut the gift of avian perception—does not lessen the scene’s emotional clarity. This extended duet is ravishingly sung by both artists and provides the most beautiful music of the opera, even if it wears its Wagnerian influence a bit too prominently on its sleeve.

More is the pity, then, that its spell is deflated by the utterly silly and musically pedestrian ballet that follows. This sequence, the celebration of the new city’s completion and its first marriage—between the danced roles of the Pigeon and the Dove—seems as pointless as the worst second-act grand operatic ballets of the nineteenth century, and culminates in the presentation of severally newly-laid eggs, a climax no less embarrassing for its being utterly predictable. I watched the scene thinking how usefully it could be cut from the opera, but in fact it does serve as a needed buffer, shifting attention from the love scene back to the central plot of Ratefreund and the Bird City.

This happy community soon has its collective feathers ruffled by the arrival of Prometheus (a powerful Brian Mulligan), whose haggard appearance and message of an approaching and vengeful Zeus bring to mind Jokanaan. His scene adds a needed dose of gravitas to the proceedings, though you may be distracted by apparent leitmotives that seem derived directly from those in Der Ring des Nibelungen or, in a reference too on-the-nose for its own good, the final scene of Salome (John Adams did this more effectively in Nixon in China).

The ensuing storm is effectively orchestrated, but leads to a denoument that completely reverses Aristophanes’s ending and, implicitly, the entire meaning of his play. Instead of Ratefreund cleverly negotiating a victory over the gods, as in the original, Braunfels has an unseen (though briefly heard) Zeus lay waste to the city, restoring the mythological ancien regime. The birds plead for peace in a lovely hymn of abasement to Zeus, and Ratefreund and Hoffegut are left alone, the latter wondering whether the whole affair was a dream. His dim recollection of the Nightingale, and her final wordless song leave us suspended somewhere between A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Wizard of Oz.

If the foregoing gives the impression that Die Vögel is in many ways a patchwork of musical ideas, dramatic themes, and character-types borrowed (not to say stolen) from earlier German opera, it isn’t to say that the work isn’t full of engaging music and emotionally satisying moments, particularly in the subplot—for whatever Braunfels’s intention that’s all it amounts to—of Hoffegut and the Nightingale. Jovanovich gives far and away the most compelling performance, lightening his Heldentenor when necessary to a more lyrical, Mozartean hue.

Rancatore has less ground to cover emotionally, but dispatches her high-flown coloratura with finesse; likewise, Mulligan is someone to keep an eye on. The rest of the cast is never less than charming, though it’s hard to tell at times if Johnson’s bellowing bluster is a character choice or a vocal limitation. Conlon leads the orchestra through a glowing account of the score.

The stage production is never ugly and sometimes clever, as with the mini-Parthenons mounted on poles, birdhouse-style, that represent the city. But the whole affair looks terribly cheap. The main set pieces (designed by David P. Gordon) are a series of waist-high clouds with lights inside them, and the colorful costumes for the birds (by Lindo Cho) feature various combinations of capes, cloaks, skirts, and robes to represent wings. Characterization through Personenregie (Vögelregie?)

Anyway, directed by Darko Tresnjak) is limited to bobbing heads and, inevitably, flapping arms, as the birds walk around flightlessly on the stage. Actually one bird (a supernumerary) does cross the stage in a Foy flying rig twice—at the end of each act, from left to right in exactly the same way each time, arms waving. The whole problem looks like a lack of ideas than a lack of funding, and while Die Vögel probably doesn’t merit the production budget of a repertory work, it certainly deserves better than a college opera-theater workshop production.

I would eagerly return to this opera, ideally in a better production (dare we let Julie Taymor loose on it?), but in the end I can only be ambivalent about its politics. Braunfels’s major reversal of Aristophanes’s ending to the play is clearly reactionary. I suppose in 1920 the prospect of a sucessful avian uprising against the gods struck a nerve at a moment when socialist revolution was considered a worldwide danger (this was the period of America’s first Red Scare, after all).

Yet considering the oppression experienced by the composer himself a decade later under a far right-wing government, today’s audiences may find the ending, and the “Groß ist Zeus” chorale, a little chilling. The anarchic ending of the original Greek play, typically for Old Attic Comedy, carries a more cynical sentiment: politics is for the birds.

Comments