Igor Stravinsky was a bit of a musical shapeshifter in his day, especially when compared to his contemporaries in early 20th century Europe. Given, the time in which Stravinsky was living in Europe was one of the most dynamic periods in recent history, but few were able to consistently generate music of such varying style as effortlessly and beautifully as he. This mastery of diversity can been seen clearly in the triple bill of Stravinsky works which was presented at The Met in 1984 titled simply: Stravinsky.

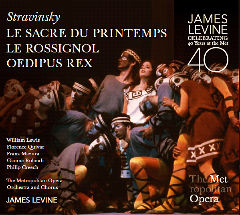

The recording of this broadcast will be included in the James Levine: Celebrating 40 Years at the Met – CD Box Set. And rightfully so, as it illustrates Levine’s incredible control of an orchestra and deeply convincing interpretations of psychologically intense music.

The evening begins with Stravinsky’s most famous work, Le Sacre du Printemps. This brutal reading, highlighted by intense rhythmic accents and beautifully phrased melodies. The depth of sound that Levine coaxes out of his orchestra is a wonder, aggressively regal at times, highlighting the native nobility of The Chosen One. The orchestra is almost mechanically precise, but also vibrantly emotive throughout the course of this wonderful performance.

Next on the docket that evening, and on the CD, is the rarely heard first opera by Stravinsky, Le Rossignol. Based on the children’s story by Hans Christian Andersen, this tale of a magical Nightingale that heals the Emperor of China is deceptively emotionally complex. Indeed, Puccini wasn’t the only major opera composer in the first decade of the 20th century fascinated with the Far East, as Le Rossignol is full of those sounds which we associate with the Orient.

It is striking in another way as well, though. Begun in 1908 and put aside until after the completion of his commissions from Diaghilev, which included Firebird and Le Sacre du Printemps, the score bears the marks of Stravinsky’s more romantic and folksy early compositional style, as well as some brutal and dissonant marks of his Primalistic phase which so famously peaked in 1913, especially noticed in the difference between Act I and Act II.

As the magical nocturnal fowl, Gianna Rolandi easily tosses of the long stretches of coloratura with a graceful agility and a beautiful, even timbre. Tenor Philip Creech doesn’t have the easiest or most aurally pleasing top register, but the sound is one fitting a weathered fisherman, who narrates the story throughout. Morley Meredith‘s blustery Emperor is best towards the end when he welcomes the Nightingale back to his kingdom with a sombre appreciation that is truly touching.

Last on the program is Stravinsky’s Opera-Oratorio Oedipus Rex. This very concise telling of the middle part of Sophocles’ Oedipus Trilogy is a noble piece of musical theater, with moments of regal grandeur that would make kings blush juxtaposed with the intimate psychological intensity of one of the world’s great pieces of drama. Not yet settled in his Neo-Classical style, the beginnings of Stravinsky’s evolution are very evident but not without direct application to the drama. Especially under the commanding baton of Levine, the score rings with beauty and power that reminds you of composers past, while still belonging entirely to Stravinsky’s own unique voice.

Anthony Dowell is the Speaker for the performance, and his finely articulate British accent lends an austere but somehow cold feeling to his summations of the action on stage; almost as if a Shakespearean actor were reading the nightly news. William Lewis‘ Oedipus has the bite and command that one would expect out of an Oedipus, although he has a slightly older sounding voice than I would expect from a young king. He still forcefully projects his full lyric tenor, and I don’t mean that as a slander.

Florence Quivar‘s Jocasta wonderfully illustrates the horrible turn of events that befall her in almost an instant with heartbreaking legato and a tone that ebbs from warm and sensual to saddened and defeated by the end of the opera. Special note should also be given to a wonderful turn by the Met Chorus in this piece.

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

Latest on Parterre

Win tickets to Piotr Beczala at Carnegie Hall!

pb—with our friends at Carnegie Hall—is giving away two tickets to PB’s December concert. Enter now!

pb—with our friends at Carnegie Hall—is giving away two tickets to PB’s December concert. Enter now!

Win tickets to Piotr Beczala at Carnegie Hall!

pb—with our friends at Carnegie Hall—is giving away two tickets to PB’s December concert. Enter now!

pb—with our friends at Carnegie Hall—is giving away two tickets to PB’s December concert. Enter now!

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments