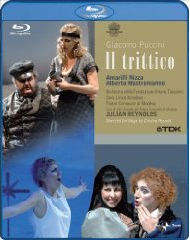

A recent production of Il Trittico, recorded in Modena, was originally published on DVD by TDK two years ago. However, its new release on Blu-ray

— along with the attention this Puccini masterpiece has received thanks to a handful of recent high-profile productions — has prompted me to take another look.

Although this video was filmed live in a single evening at the Teatro Comunale of Modena, the production toured several towns in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna over many months, with occasional changes of cast and conductors. The opera houses that hosted Trittico may be part of the Italian regional operatic circuit, but the result is first-class and worthy of the biggest companies. It is a supreme proof that it is possible to create stimulating and beautiful looking productions even with limited resources.

The merit is to be ascribed chiefly to stage producer Cristina Pezzoli, a pupil of Dario Fò. With a background primarily in straight theater, prior to this Trittico her operatic experience was limited to a production of Cavalleria rusticana and Gianni Schicchi.

Ms. Pezzoli, together with set designer Giacomo Andrico, has chosen to set the three operas in the period of their composition, World War One. Even though the three works are very dissimilar, Ms. Pezzoli has found a common denominator: death and decadence are the central figures in all three episodes. She argues that Puccini is describing a world on the point of collapse, which justifies setting the works in a time of radical epochal change like the second decade of the 20th century.

Inspired by the letter Puccini wrote to his Tabarro librettist, Giuseppe Adami, in which he says that the Seine river should be the true protagonist of the drama, Pezzoli sets Michele’s barge right under a bridge, so as to emphasize the sense of claustrophobia innate to the drama. The river is indeed physically present, so much that Michele tries to drown Luigi plunging his head into real, splashing water. The effect, with Luigi wet and gasping for hair, is true to the verismo style of the opera.

Cloister and claustrophobia share the same etymology. Pezzoli’s convent in Suor Angelica is an imposing structure with many shaded corners to which Angelica often withdraws so as to hide herself and avoid the other nuns’ gossiping in the first part of the opera. Tall marble columns glide to and fro in an extremely smooth and unobtrusive manner in order to provide the right sets for each particular moment. Thus, a fountain comes in and out, as do the gratings and the benches needed for Angelica’s confrontation with her aunt.

The end of the opera is simple, yet moving. As the set empties out, the nuns come in carrying crosses they stick into the ground, creating a cemetery. The miracle scene, the trickiest moment of all the Trittico, is successfully staged. While giving away no details, I will say only that it managed to be appropriately touching without being corny and mawkish.

Life in a cloister hasn’t changed much over the centuries, and the only sign of period updating was the Princess’s costume. In Gianni Schicchi, however, the change in era is more problematic. This opera is firmly situated in a very specific historical moment, September 1, 1299, as the Notary states in the libretto, not to mention that the protagonist was a real life person sentenced by Dante to live for eternity in hell. Gianni Schicchi is also the least realistic of Pezzoli’s mise-en-scenes. Buoso Donati’s relatives are comically dressed, resembling clowns, with the clear intention of emphasizing the decadence of their social class.

Amarilli Nizza portrays all three heroines. I first heard Ms. Nizza several years ago as Elena in I vespri siciliani, and Leonora in Il trovatore, roles I did not find at all suited to her voice. I subsequently saw her as Aida in Verona, and found her only moderately more successful. She is definitely more at home with Puccini. Gifted with subtle, nuanced fraseggio and crisp diction, she appears comfortable in Puccinian “conversational singing”. She is an intense interpreter and a compelling actress, moving on stage with naturalness and spontaneity.

Ms. Nizza’s voice is far from being conventionally beautiful. The central register, between middle G and high G, has a tight vibrato that many may find sour and unattractive, but which reminds me of Italian sopranos of yore, such as Clara Petrella, Iris Adami Corradetti, Augusta Oltrabella and even Magda Olivero. Her top, however, however superlative. “È ben altro il mio sogno” is capped by a splendidly nailed high C, which she holds forever. The same can be said for the high C in the duet with Michele, as well as for those in Suor Angelica. The ten high As on the phrase “Madonna, salvami”, sound effortlessly glorious. It is refreshing to find someone who can act the fervid, impassioned death scene without worrying whether her high notes will turn into screams.

Although I would prefer a more charming, sweeter voice in Gianni Schicchi, her Lauretta is nonetheless successful because of her approach to the role. Completely devoid of syrupy sentimentalism, she sings “O mio babbino caro” like a spoiled brat who has no problems wrapping her daddy around her little finger, creating a comic cameo.

Alberto Mastromarino plays both Michele in Il tabarro and the title role in Gianni Schicchi. His baritone, though not particularly distinctive, is sturdy and reliable. A few high notes sound perilous, but in general his vocal performance is competent and proficient. He is an effective actor; his natural bearing on stage, his menacing, brooding looks in Tabarro and his swiftness and fleet-footedness in Schicchi makes the audience overlook his undeniable portliness. While Mr. Mastromarino’s voice may not be one for the ages, he is undoubtedly one of those singers who are necessary to the prosperity of smaller opera companies.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Annamaria Chiuri, who sings the three lead mezzo-soprano roles. Her sopranoish voice is dry and short in range. If this can be tolerated in Tabarro and Schicchi, it is unforgivable in Suor Angelica, where her insubstantiality brings considerable damage to the chilling duet between Angelica and her inexorable aunt.

As Luigi in Il tabarro, Rubens Pelizzari has a somewhat generic spinto tenor, virtually undistinguishable from many other similar artists. What he does have is a valuable facility around the passaggio, a skill that proves helpful in the duet with Giorgietta, the Andante mosso moderatamente “Vorrei tenerti stretta,” where Puccini forces the tenor to hammer away at an endless series of high Gs sharps and As, with a fiendish acciaccatura on a B natural.

Andrea Giovannini’s performance as Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi suffers the most from the director’s decision to present him as a downright clown. His light but pleasant instrument is overwhelmed by his buffoon’s appearance and behavior, which make it difficult to see him as an “amoroso” and which is in partial conflict with the melodies Puccini assigns to him.

The numerous secondary roles are aptly cast (with the exception of a particularly bad Tinca). They are all good actors, and their being mostly Italian gives the operas an aura of authenticity, which is sorely missed when conversation oriented works like these are filled with non-native singers. In Gianni Schicchi, for example, the cast is fittingly instructed to sing with a pronounced Tuscan accent, a detail I found particularly charming.

Conductor Julian Reynolds wins no prizes for originality of interpretation, but leads the orchestra in a precise and correct way, and, what’s more, seems to be particularly attentive to the singers’ needs and exigencies. The Orchestra della Fondazione Arturo Toscanini is well above the average level of provincial ensembles.

Loreena Kaufmann’s TV and video direction has a definite cinematographic approach, with unusual high and low angle- shots, and even more so with her POVs. When Michele tries to drown his rival, the camera is in the water and shows Luigi’s head being pushed towards the viewer. It’s quite effective. This recording is decidedly more animated and spirited than the average opera video.

Comments