Photo by Steven Pisano

The arc of Complications in Sue, Opera Philadelphia’s current world premiere, is unimaginable without…well, ARC. That is, of course, Anthony Roth Costanzo, OP’s General Director and President, who has been audaciously reinventing the company since he took hold in 2024.

Who else could have assembled a roster of luminaries with this kind of cutting-edge glamour? The librettist is Michael R. Jackson, the Pulitzer and Tony-winning visionary behind A Strange Loop. The basic idea for Complications in Sue came from Justin Vivian Bond, the legendary gender-bending-and-defining performance artist. Collaborative directors Raja Feather Kelly and Zack Winokur are noted names in au courant dance, theater, and opera circles. As for the composers (yes, plural), they include Missy Mazzoli, Nico Muhly, Cecile McLorin Salvant, Rene Orth…and the list goes on.

Yes, who but ARC could have made this happen? In this case, he didn’t himself take to the stage, beyond introducing the opening night performance to tumultuous applause. But there was never any doubt that this is an ARC event (an Arc-vent??).

But what is “this”?

Certainly, that was my question going in, and frankly I was dubious. I expected this new work to be showy and fun—the kind of pièce d’occasion that succeeds by making a big celebratory statement—but nothing substantial, and not a piece likely to have much of an afterlife.

I couldn’t be happier to be proved wrong on both counts. Let there be no doubt: Complications in Sue absolutely is an opera. And a very fine one.

As you might already have picked up, the title is both a pun (on “complications ensue”) and an accurate description. What we have here is a biography of the titular “Sue,” told from birth to death in a set of short (8 to 10-minute) vignettes that sequentially cover ten decades: from her birth to her death at 99. “Sue” is played here by none other than Bond themself—a celebrated performer, but certainly not an opera singer. Their voice, an effective cabaret instrument, is more of a boozy baritone in the Elaine Stritch vein.

Complications still doesn’t sound like an opera? So, let me tell you why it is.

The core of the work is a collection of through-composed scenes by a wonderfully gifted and imaginatively assembled group of stellar musicians. (To the ones I’ve already mentioned, add Andy Aikho, Nathalie Joachim, Alistair Coleman, Kamala Sankaram, Dan Schlossberg, and Errolyn Walton.)

Each composer has their unique sound worlds, of course, but there is an astonishing sense of cohesiveness to the work, which emerges with a sound world that is contemporary and often witty, but also has some very melodic passages. It is not fundamentally a chamber opera—there are brass instruments and percussion in the excellent orchestra (superbly conducted here by Caren Levine).

Yet to me, the work has a sense of chamber music in many ways. Though sometimes edgy, it’s also warmly nostalgic, or at least bittersweet. Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 came to my mind more than once.

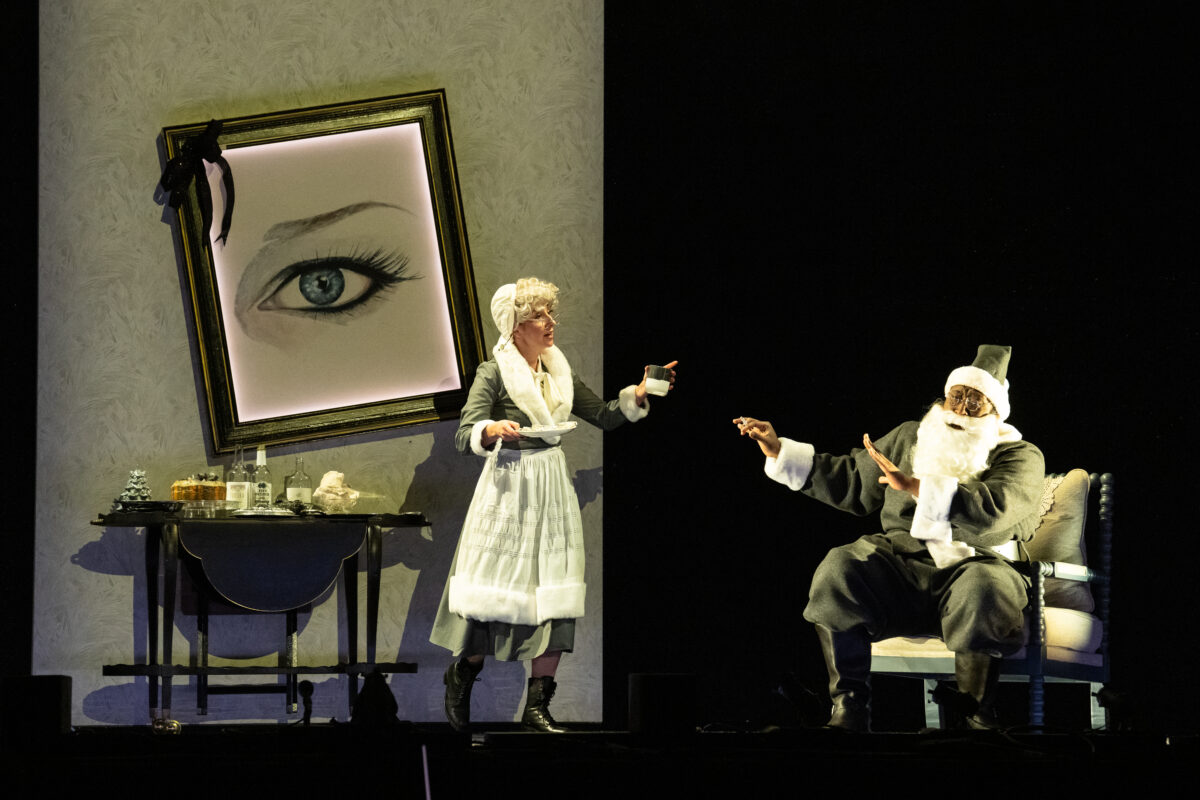

Complications, like Knoxville, is a character study that is at once ordinary and profound. Sue’s life has the usual ups and downs, beginning in a childhood where her need to believe in Santa Claus is tested by Santa himself, who has had quite enough of his own job. (This sets in motion a darkly humorous tone that underscores much of Complications.) Moving on, we see Sue through years of school; with friends and rivals; in a romantic relationship (with Roger) that works and doesn’t work; and ultimately, her last minutes on earth as she’s escorted away by Death themselves. (It’s not a spoiler to say that the piece suggests life ends as it begins.)

Photo by Steven Pisano

Fundamentally we come to understand Sue through an evolving group of people who surround her. This is the “operatic” cast of singing actors who play multiple roles as well as functioning as a collective narrator. They are tenor Nicky Spence, baritone Nicholas Newton, and soprano Kiera Duffy—all superb in every sense, with Duffy particularly dazzling in some very stratospheric writing. The cast also includes mezzo Rehanna Thelwell, who though indisposed mimed the role on stage. It was sung by cover Imara Miles—an absolutely gorgeous, lush mezzo who clear is a rising star. Sue herself was played here by Justin Vivian Bond. (More on that in a minute.)

I rank Complications in Sue as a major success for Opera Philadelphia, and an exhilarating sign that for the company, ARC is indeed its Arc de Triomphe.

Still, I have a couple of reservations.

The first has to do with the staging, which by any standard is dazzlingly conceived and executed, full of brilliant theatrical strokes and eye-popping design (set by Krit Robinson, lighting by Yuki Link, costumes by Victoria Bek and JW Anderson). But the humorous tone that works so well at the beginning feels increasingly out of kilter with the evolving and darkening nature of the work itself, though a final lump-in-the-throat image is unforgettable.

My second reservation is likely more controversial, and that has to do with Bond themself. As mentioned, they are the co-conceiver of this piece. More to the point, Bond is a true icon, a hero in the world of gender portrayal in the arts—and that imprimatur is felt throughout Complications in Sue. Their presence lends a luster that also helps define Sue as both human and larger-than-life.

Photo by Steven Pisano

But as a performer, Bond doesn’t settle easily into this work. The singing is limited to a ditty which is delivered with style, but doesn’t offer much beyond that. There is virtually no spoken dialogue until a long monologue where Bond, completely breaking the theatrical frame, excoriates all things Trump and Trump-identified. This brought down the house (no one would mistake an Opera Philadelphia performance for a Turning Point USA rally), but for me, it’s an unwelcome, grandstanding distraction from the work itself.

I do believe Complications in Sue has a future—and one that will almost certainly not involve Bond’s physical presence. Which for me is as it should be. One of the remarkable things about the work is that Sue herself is essentially an observer; her active participation in speaking, singing and even physical presence is more felt than seen. Remove the character and you lose very little. In fact, in many ways I think you gain something—we come to know and care about Sue through the people around her. By the end, they have thoroughly and generously brought Sue to life… and moved us as an audience. What more can we ask for?