Photo by Michele Crosera

Simon Boccanegra is set in Genoa but had its premiere in Venice in 1857; Verdi’s librettist Francesco Maria Piave was Venetian, born on Murano, from a family with a business in Murano glass. In 1881 Simon Boccanegra was substantially revised for La Scala, Verdi now collaborating with Arrigo Boito, as they prepared to take on Otello together, and this revised version is the one we invariably hear today. Nevertheless, Simon Boccanegra performed in Venice still feels like a homecoming, and a thrilling new production opened at La Fenice on January 23, conducted by Renato Palumbo from the Veneto region, directed by Luca Micheletti who is also a celebrated operatic baritone, and starring, as Boccanegra, Luca Salsi, the preeminent Italian baritone of his generation, heading an all-Italian cast.

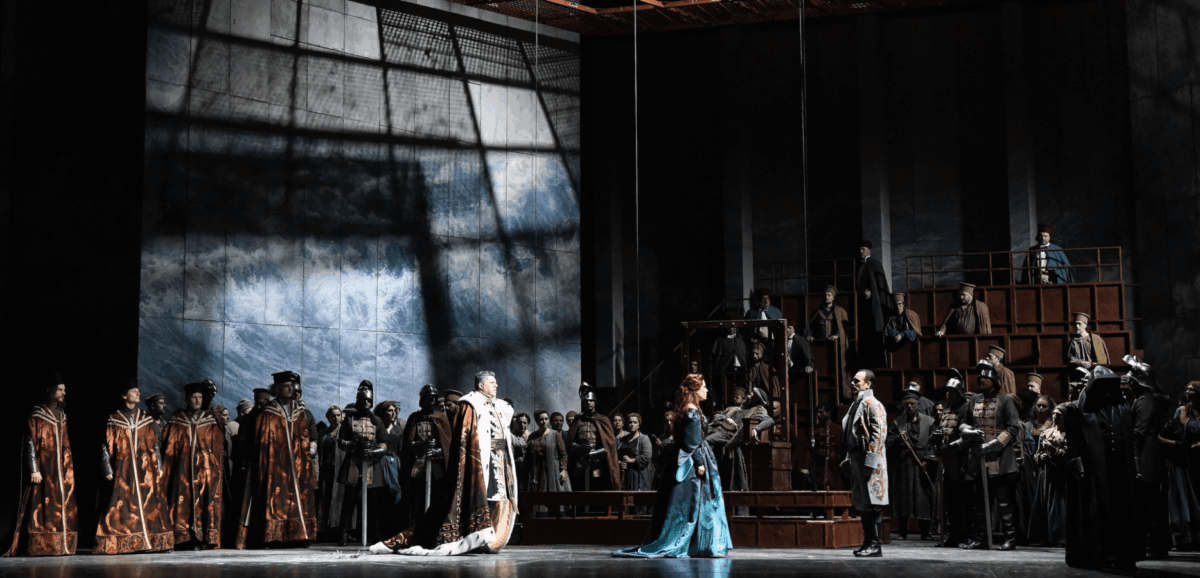

The medieval Genoese scenario of Simon Boccanegra could have been a reflection of Venetian history, for a “doge” (like Boccanegra) could have been the elected leader of either the Genoese or the Venetian republic, longstanding maritime rivals in Mediterranean trade. Like Otello, Simon Boccanegra is a seascape opera, relatively rare in Verdi’s vast oeuvre. From the first bars of the prologue, with gently rocking pairs of eighth notes in the violins and broader rolling phrases of the violas and cellos, the currents of the Mediterranean are a musical presence. Boccanegra himself is a corsair who has spent his life at sea, battling with North African pirates (and is probably a semi-pirate himself), but now acclaimed by the plebeian party as the Doge of Genoa. Verdi set up a dramatic contrast between the romanticized freedom of life at sea, renounced but wistfully remembered, and the oppressive constraint and conspiratorial menace of political life. Micheletti’s production offered Mediterranean views of waves and foam. The stark set marked by a long diagonal staircase gave almost the sense that the characters were disembarking as they entered the scene.

Simon Boccanegra is disturbing political opera, created ten years after Macbeth and ten years before Don Carlos, and suggesting a similarly sinister Verdian view of political life. The opening scene of Simon Boccanegra was marked to be sung mezza voce, the musical dynamics of whispered conspiratorial conversation. Paolo, the political villain, plots to make Boccanegra doge and then begins to manipulate the chorus that represents the plebs of Genoa, raising his baritone voice only in soliloquy to denounce the “aborriti patrizi,” the hated patricians. Patrician Fiesco enters to sing the beautiful basso arias, “Il lacerato spirito,” darkly accompanied by pianississimo bassoons, horns, trumpets, and trombones, and an offstage choral Miserere; he is mourning a daughter who ran off with a lover but came home to die. He will soon discover that her lover was none other than the corsair who is about to become doge, and Fiesco’s paternal and patrician hatred will pursue Boccanegra throughout the opera. It is Paolo, however, the plebeian demagogue, who will administer the fatal dose of poison that ultimately kills Boccanegra. Paolo’s resentments and his murderous fury at the doge he created, but could no longer control, were vividly characterized by baritone Simone Alberghini, while Fiesco’s more grandly patrician vindictive rage was given a seering emotional performance by bass Alex Esposito.

In 1857 the opera received a mixed reception in Venice, and it was even suggested that there was an antagonistic Jewish cabal favoring the work of Venetian composer Samuele Levi. “Are the Venetians now tranquil?” Verdi wrote. “Who would ever have thought that this poor Boccanegra, whether a good or a bad opera, would provoke such devilry!” Politics was at work again in 2026 with untranquil Venetians inside and outside the opera house signaling hostility to the recent appointment of conductor Beatrice Venezi as musical director of La Fenice; she is seen as suspiciously close to the right-wing circles of the government of Giorgia Meloni in Rome. The possibility of a government plot to exercise greater control over the arts was perfectly attuned to the conspiratorial politics of Simon Boccanegra, though Venezi is not scheduled to take over at La Fenice until later this year.

Twenty-five years pass betwen the prologue and first act of Simon Boccanegra, an unusual chronological gap within an opera libretto. In this way, it curiously resembles Boris Godunov, with its time jumps and the troubled deaths of its leader taking place on stage.

Photo by Michele Crosera

As in the prologue, Verdi opens the first act with another musical seascape, now in lilting 9/8 time, Lento assai, with trilling violins, rapid piccolo arpeggios, and flute triplets; it is dawn and a young woman Amelia, performed by Francesca Dotto, descends a staircase in a sea-green gown, singing, “Come in quest’ora bruna/ sorridon gli astri e mare” (How at this dark hour/the stars and the sea are smiling). Dotto sang with lovely purity of tone in an almost Mozartean mode (she has sung both Donna Anna and Fiordiligi), though some of her top notes sounded forced when the score called for more dramatic singing. Her calling card has been Verdi’s Violetta in La Traviata, but her bel canto skills counted for little as Amelia, since Verdi ruthlessly eliminated the ornamented cabaletta from this opening aria when he revised the 1857 score. Hers is the only female voice among the principals, and she is loved by all the men in very different ways, while they remain also thoroughly preoccupied with politics.

The man she herself loves is Gabriele Adorno, sung by Genoese tenor Francesco Meli in superb voice with heroic top notes, exciting squillo, delicate phrasings, and fierce passion. His beautiful act-one duet with Amelia does have a sort of cabaletta, with the scene pivoting on the arrival of the doge— “Il doge qui!”exclaims Adorno angrily, and they shift from cantabile dolcissimo to allegro brillante. In Amelia’s next duet with the baritone Boccanegra Dotto was at her loveliest as she recalled her orphaned childhood, singing with oboe obbligato; that orphan child also wandered the stage as a mime.

Salsi was a commanding vocal presence as Boccanegra, with the widest range of vocal dynamics from a whisper to an outcry, presenting a darkly resonant vocal timbre in which every syllable was imbued with emotional meaning. The Verdian template for this baritone role was clearly Macbeth, a character who allowed Verdi to dispense with conventional aria forms and create a musical equivalent of Shakespearean declamation, allowing for every subtle variation in dynamics and emotions. Boccanegra has not a single aria to call his own, and almost his entire musical existence is constructed in relation to the other characters. Like Macbeth, he has been suddenly elevated to the apex of political power and owes his elevation not to murder exactly but to the intervention of a murderous villain, Paolo, who thereafter regards Boccanegra as his political creature.

In the Council Chamber scene that Verdi created brand new for the 1881 version, inspired by the poetry of Petrach from the fourteenth century, Salsi made his cry for peace (“E vo gridando pace”) into the desperate plea of a political leader with a troubled soul, though the call for Ligurian and Adriatic amity, from Genoa to Venice, in the transcendent key of F-sharp major, also expressed Verdi’s own political dedication to Italian unity, achieved in the 1860s. Verdi allows a hint of ornamentation on the word “pace” and then a very moving high baritone F-sharp, together with the woodwinds, as Boccanegra cries out again. The cry for peace holds a particular resonance in 2026, especially when world leaders were meeting at Davos trying to salvage what was left of the international order after the American president all but shredded the Western alliance, denounced America’s allies, threatened war in several different directions, and, with Orwellian doublespeak, invited far-flung dictators to join a global “Board of Peace.”

As a character, Boccanegra perhaps comes together most brilliantly as he falls apart during the third act, succumbing to Paolo’s poison, and eventually dying on stage. Salsi was mesmerizing in this scene of irregular declamation and exclamation, of whispered reminiscence and delirium, taking him back to the world of the sea that he abandoned back in the prologue. Over tremolo violins he sings an expansive phrase, refreshed by the sea breeze, and then, echoing music from the prologue, the score shifts into rolling 6/8 time and Boccanegra sings and repeats a lovely descending phrase that caresses the syllables of “il mare, il mare” (the sea), as he remembers the maritime scene of “sublime ecstasies.” After a gripping reconciliation with the now very old patrician Fiesco, and a deeply moving quartet for the principals, Boccanegra finally dies by disappearing into the seascape of his memories, beautifully directed by Micheletti.

Photo by Michele Crosera

The 25 years that separate the prologue from the plot of the opera’s three acts were paralleled by the roughly 25 years that separated the two versions of 1857 and 1881. Micheletti’s strong directorial sense that the past of the prologue continues to resonate throughout the opera. That Boccanegra is haunted by his past, connects to the arc of Verdi’s own artistic development: Simon Boccanegra as an ambitious mid-century work of the composer’s middle age, reconceived as an already autumnal masterpiece in 1881. The world changed considerably between 1857 and 1881 with the invention of the elevator, the lightbulb, the typewriter, and the telephone, not to mention dynamite, torpedos, and machine guns. When Verdi and Boito created Boccanegra’s plea for peace in 1881 a new age of Mediterranean imperialist struggle was about to begin: in 1879 the British and French deposed the Egyptian Khedive Ismail (who had commissioned Verdi’s Aida in 1871), and in 1882 the British occupied Egypt as a colonial protectorate. In 1881 the French established a protectorate in Tunisia, causing outrage in Italy which also had Tunisian ambitions. When Verdi in 1881 was asked about a Paris production of Simon Boccanegra, he snapped back: “You’re crazy (sei matto)!! Give Boccanegra in Paris?!! Do you think I would go there at this moment? Never! Not for all the gold in the world!”

Before dying Boccanegra indicates the patrician Adorno as his successor, and the peaceful passing of the dogeship to the next generation tentatively seems to promise a less divisive political future. Simon Boccanegra with its unusual timeframe— spanning an entire generation in medieval history, and decades of Verdi’s own creative life—compels us to reconsider the relation of the operatic past, present, and future. The shifting political landscapes and seascapes of Simon Boccanegra encourage us to reflect on how the poisonous politics of the present may be rooted in the unexplored intricacies of a past that we possibly failed to recognize as the historical prologue of things to come.