Vincent Pontet

Many of us have been grateful over the years for all the pleasure, the sheer enjoyment brought to us by Laurent Pelly and Marc Minkowski, starting more than two decades ago with memorable productions of Offenbach standards, including, La Belle Hélène and La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein, both with Dame Felicity Lott, and Orphée aux Enfers with Natalie Dessay. They were also jointly responsible for establishing Rameau’s Platée, and thereby Rameau himself, as a repertoire classic at the Paris Opera. The last collaboration of theirs that I witnessed was La Périchole, also at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées (TCE) three years ago, as it happens with Stanislas de Barbeyrac.

Naturally, when the 2025-2026 schedules appeared, Robinson Crusoé, an Offenbach rarity, with Pelly and Minkowski at the helm, was one of the most exciting prospects of the new season. To be sure of having good seats, I even went so far as to take out a subscription at the TCE again.

Robinson Crusoé had its premiere in November 1867 at the Opéra Comique. The stakes were high. The joke had been made that even Boston or Rio were within easier reach for Offenbach than ‘Favart’ (i.e, than the Opéra Comique, housed in the Salle Favart). His first foray there, in 1860, an opéra bouffe called Barkouf, was a flop, running for only half-a-dozen performances. This was presumably because Barkouf was, indeed, an opéra bouffe, not the generally more sedate Opéra Comique fare.

So for his 1867 return to the prestige house with Robinson Crusoé, Offenbach pulled out all the stops. He turned, for his text, to Eugène Cormon, stage manager of the Paris Opera (in charge, for example, of Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine), and Hector Crémieux, author of a baker’s dozen or more of his librettos, including (with Halévy) Orphée aux enfers. And he assembled a prestige cast. Achille-Félix Montaubry (Robinson) had been Berlioz’s first Bénédict. Marie Cico (Edwige) was an Offenbach regular, having sung in Orphée aux Enfers and Geneviève de Brabant, among others. Célestine Galli-Marié (Vendredi) had just premiered Thomas’s Mignon and would go on to star in Fantasi—and in Bizet’s Carmen.

In the event, the work was neither a smash hit nor (no pun intended) a shipwreck. The press seems to have thought it wavered too ambiguously between the opéra-bouffe and opéra-comique genres. The audience applauded the bouffe numbers at the core of the work most loudly, and some were encored, but they were less enthusiastic about the whole.

The score was criticised for containing “too much music,” a jibe that must have driven many composers crazy over the centuries, Rameau being the first that comes to my mind. It is strikingly inventive, colourful and sophisticated—one of Offenbach’s best. Measured reception or not, it was hailed by the more musicologically-focused press as marking a new stage in Offenbach’s development as a composer, confounding those who saw him as ‘condemned to the Bouffes’ (meaning, with its capital ‘B’, the theatre where his bouffe works were usually performed) ‘à perpétuité.’ Robinson Crusoé ran for a respectable, if not record-breaking, thirty-two performances.

My thought, as the performance ended on Monday evening, was that if this relentlessly energetic production doesn’t restore Robinson Crusoé to the repertoire, nothing can. It certainly deserves it—unless, a genuine concern, its period references to savages and cannibalism, and the pidgin English of Venerdi (the equivalent of Defoe’s Friday) prove too hard to render acceptable. Pelly on stage, Minkowski in the pit, and an outstanding cast all round showed that any potential ‘placidity’ in the first act, or the potential bathos of the ‘glory be’ denouement (quite common, after all, in this genre) can be swept aside by lively directing, vigorous conducting and top-class singing. There’s no chance of the audience’s attention flagging.

Vincent Pontet

The title role of Robinson was originally meant to be sung by Lawrence Brownlee, but apparently, the Paris Opera put a contractual kibosh on that. Malagasy tenor Sahy Ratia was brought in to replace him; an equivocal honor, I should imagine, for someone only just starting to make a name for himself. Ratia describes himself as a tenore di grazia or light lyric, in the same vein as Brownlee and Flórez. He has, I read, recently triumphed in Satyagraha and as Nadir in Les pêcheurs de perles. His voice is undeniably youthful, even a touch ”‘green,” though firm and well projected. He oozes youthful charm—perfect for Robinson. It will be interesting, one day, to hear him in Rossini.

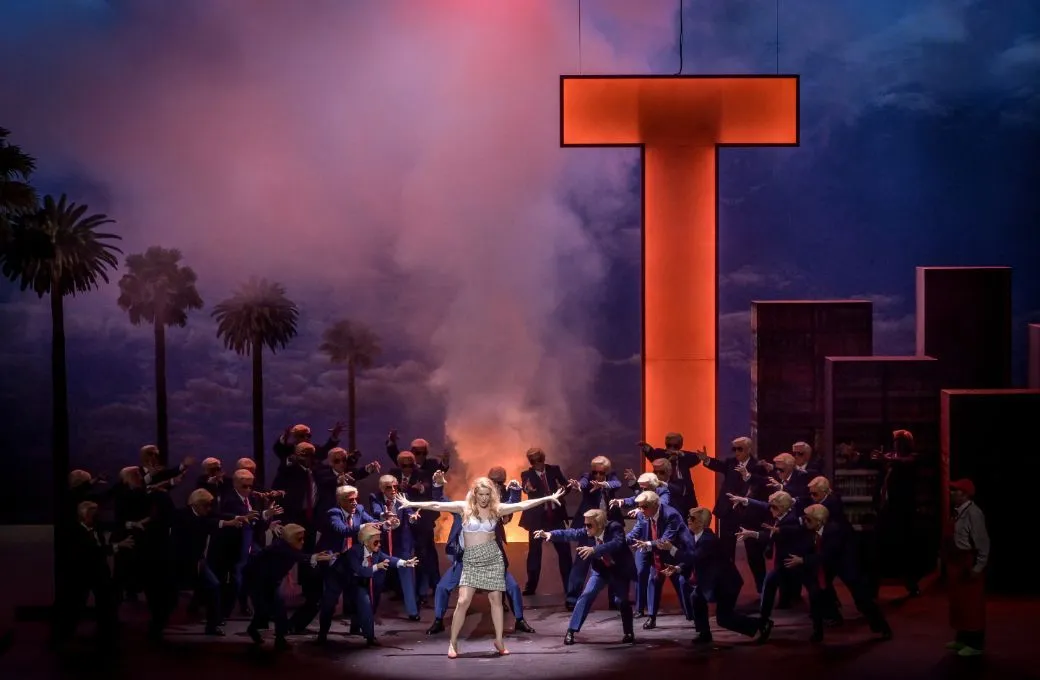

Julie Fuchs was absolutely breathtaking above all in the show’s central showpiece, the mad Valse d’Edwige, ‘Conduisez-moi vers celui que j’adore’, that some will know from recordings by Joan Sutherland, Natalie Dessay, or, with a special sparkle, the late Jodie Devos. Hitching up her (until then demure) pencil skirt and leaning into the audience as if to challenge us, with her eyes askew and a tousled mane of blond hair tossed to one side, she brilliantly channelled Brigitte Bardot in her 60s heyday. Gobsmackingly charismatic, but still, in the midst of the whirlwind hysteria, fascinatingly nuanced, tossing off deceptively easy-sounding messe di voce. We tottered out for interval drinks in a trance.

As Vendredi, Adèle Charvet was unfortunately announced sick (a stand-in had sung from the pit at the dress rehearsal) but willing to go ahead, and did a commendable job, singing with undeniable elegance, if not constant force.

Laurent Naouri is a veteran of these Pelly-Minkowski collaborations, and was totally at ease—and remarkably sonorous, without resorting to barking—as Robinson’s father, Sir William. He was ably partnered, both in song—with a deep, plummy, velvety sound—and their perky dance routines by Julie Pasturaud (Deborah).

As Toby, Marc Mauillon, the brilliant haute-contre Mercury in last year’s ‘Olympic Games’ production of Les Fêtes d’Hébé, was better-directed here than by Sellars in Castor et Pollux, a few months later, in which, as I wrote at the time, he ”‘had his baritone hat on.” Yes, unusually, he does both. Here, he was a tenor again, and in true mid-season form, throwing himself with gusto and precision timing into the comic business while singing accurately, percussively, and with excellent diction. He was partnered equally ably by the lively Emma Fekete (Suzanne), a glittering light soprano from Quebec, new to me, but one I imagine we’ll see more of in Paris after this success at the TCE.

Rodolphe Briand, who describes himself as a ‘singer who acts and an actor who sings’, was just the right character tenor for the crafty Jim Cocks. The Act Three contribution, as Atkins, of young bass Matthieu Toulouse was frustratingly brief. He has a well-projected presence; it would be interesting to find out more about what he’s capable of in the future.

Pelly gave the chorus a lot to think about (see below), which may explain that, while they certainly stayed together, they made less noise than their numbers led you to expect.

Marc Minkowski’s conducting was characteristically zingy and invigorating; at times, as he whips the score into a frenzy, his baton might be a riding crop. But this has the advantage, along with Pelly’s lively, sometimes corny stage business, of ensuring potential drops in voltage in the opening and closing scenes never become actual. The orchestra was not, on opening night, note-perfect, but compensated by bowing, blowing, and banging away with infectious, if percussion-heavy abandon.

Laurent Pelly’s production is simpler than his La Belle Hélène or La Grande Duchesse— whether for artistic or economic reasons, I don’t know, but it makes no odds. It’s no less tightly directed, with nearly every move timed to fit the score. By shifting the action northwards, it attempts to elude potential colonial-era issues.

It opens with the Crusoe household in their homely, slightly threadbare flat, set (probably in a deliberate nod to Robinson’s fate and suggesting that an English suburban villa is as much a desert island as any other) on a kind of rotating islet, with its rooms arranged around a central axis of doorways and lamps. Deliberately cheesy but good-humoured dance routines help keep things lively.

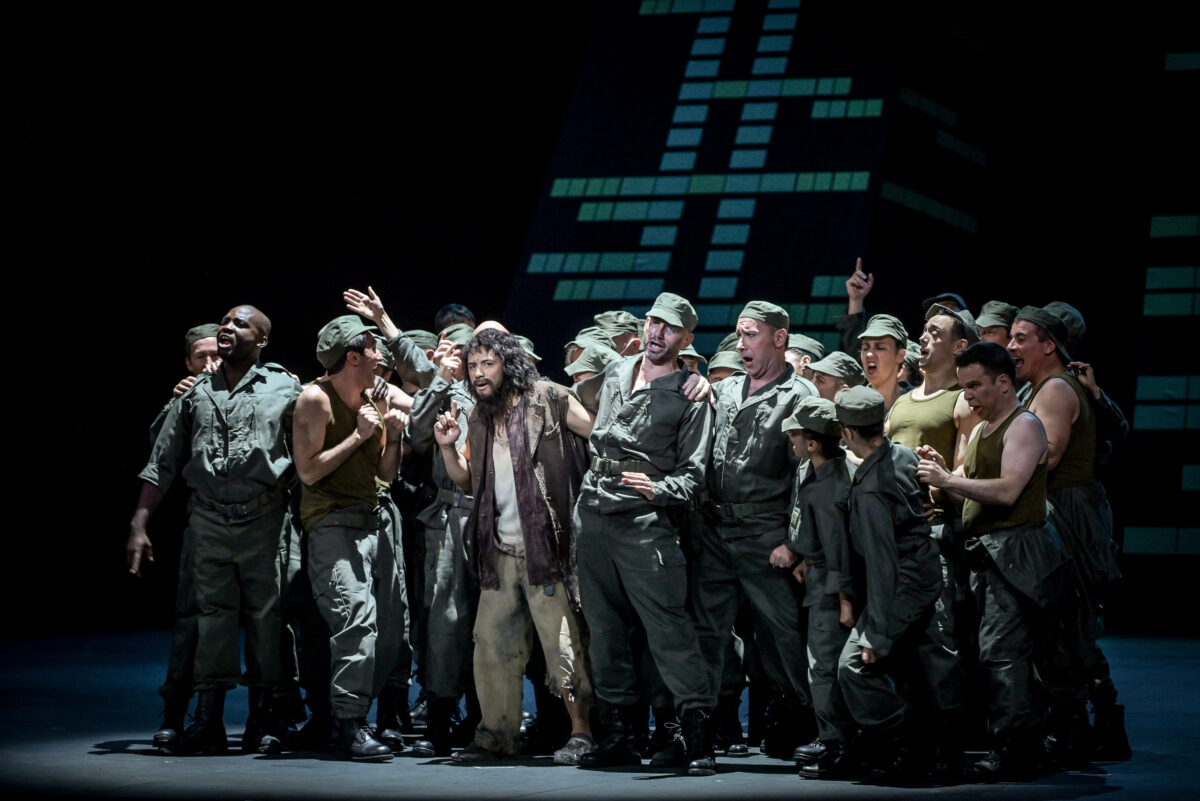

Robinson, fresh-faced and clean-shaven in a dapper tailored weskit, sets off to get rich in the Americas. We soon find him, with Vendredi, long-haired, bearded, and tattered, scraping by in a migrant tent city surrounded by corporate skyscrapers, somewhere in the US—Florida, maybe, judging by the palm trees.

While Jim Cocks explains, in his Rondeau, how he saved his own skin by introducing the locals to the delights of pot-au-feu, the staff of his gleaming fast-food emporium, in the shadow of the word ‘EAT’ in giant red letters, trundle in cartloads of human parts and hack frantically at the joints on a stainless-steel conveyor. Their uniforms are red shirts with a little yellow logo: golden arches inverted into a curvy ‘W’.

The press, faster off the mark than I am, have mostly skirted round the central gag of the evening, not wanting to spoil the surprise; but I think that, by now, I can spill the beans. The man-eaters, leering and grasping at the ‘white goddess’ Edwige, still in her prim pencil skirt and blouse but now, drugged, throwing caution to the winds, are none other than POTUS in person. The whole manically-grinning chorus, male and female, tall or short, skinny or portly, in yellow wigs, orange make-up and sunglasses, sport the infamous royal-blue suit and red tie, and do the infamous ‘“YMCA” victory dance. It’s big and crude, but a (blatant) crowd-pleaser. As I wrote above, Julie Fuchs’s gobsmackingly charismatic performance of Edwige’s showpiece waltz, surrounded by all these Trumps, was one of the evening’s highlights.

Vincent Pontet

The “pirates,” in Castro- or Guevara-style fatigues and caps, are perhaps meant to be Caribbean guerrillas of any kind. Not quite working that out didn’t spoil my enjoyment. At the very end, just before the curtain, in a neat twist, Robinson is left alone on stage, sitting under a single palm. Perhaps it was all a dream.

The whole evening was, to me, like a return to those good ‘old’ days at the turn of the present century I reminisced about at the start of this post. Now, if only Pelly and Minkowski could be persuaded to cast Mauillon (or perhaps Ratia) and Julie Fuchs in Les Mamelles de Tirésias…