Curtis Brown

Wagner singing in the United States is at something of an inflection point. Many of the singers who’ve dominated U.S. stages for the last 20 years or so are retiring their roles, or retiring entirely, and a new generation is coming to the fore.

Santa Fe Opera’s Die Walküre, its first and seemingly separate from any full Ring cycle, exemplifies this trend. A cast of younger-generation singers, some of them making their role debuts, gave terrific performances in Melly Still’s smartly directed production. Her framing of the story brings memory to the fore, the memory of things that have happened and prophetic memory, bringing forward events that occur later and characters who appear later in the Ring.

Die Walküre starts with a storm raging, and most productions focus on Siegmund, fleeing across a forest after a failed attempt to rescue a young woman from a forced marriage. But Still takes a different tack; during the prelude, we see the young Sieglinde, played by actor Mia Moore, being kidnapped, as Siegmund will later recount. The kidnappers disappear, and we then see adult Sieglinde –– in ragged, worn clothing, with dirt and bruises on her face –– in a decrepit modern kitchen, with a tiny refrigerator, filthy stove, and broken-down furniture.

When Siegmund enters, Sieglinde is terrified and faces him down with a knife, rather than immediately offering succor. He’s wearing a ragged white sweater, just like hers, and a heavy outer jacket, making an immediate visual connection between the twins. That would be a nice touch in any production, but it’s especially helpful here, with Siegmund played by tenor Jamez McCorkle, a tall Black man, and Sieglinde sung by Vida Miknevičiūtė, a small white woman.

They made a tremendous pair. Seeing McCorkle at San Francisco Opera as the title character of Rhiannon Giddens and Michael Abel’s Omar, I wouldn’t have pegged him as a Heldentenor, but here he was, singing Siegmund with a sweeter and lighter tone than most tenors bring to the role. In the singer-friendly Crosby Theater, his sensitive phrasing and beautiful legato carried the day and amply compensated for any lack of pure vocal power.

In Miknevičiūtė, he had a wonderful partner. She might be slight of frame, but she has a mighty voice, a bright, piercing soprano that she deploys with an intelligence matching McCorkle’s.

Similarly, Hunding was a great fit for Soloman Howard in every way. His height, his warmly beautiful bass, his presence were all made for this role. That Hunding is an abuser is implicit in the libretto, but Still makes it explicit with her direction. Sieglinde cowers in Hunding’s presence; she brings him beer; she kneels and removes his boots without being asked. We’re seeing the behavior of a woman in a deeply abusive relationship.

Curtis Brown

Meanwhile, atop Leslie Travers’s two-level stage, Wotan’s long-suffering wife Fricka, here the young mezzo-soprano Sarah Saturnino, watches the trio below. She’s in a white dress cris-crossed by red ribbons that reflect red cords that are used as scenic elements. Are they the Norns’ ropes of fate, which the audience isn’t aware of until the prelude to Götterdämmerung? Who knows, but it certainly makes a striking stage picture.

That set serves other purposes. It’s a perch for Brünnhilde and the other Valkyries. Flexible vertical elements serve as a screen, behind which, for example, you see Siegmund and Sieglinde cavorting during Fricka’s Act II confrontation with Wotan. People sometimes emerge from behind the screen, including, apparently, Alberich, the woman he rapes to father Hagen, and Erda, characters mentioned, but not seen, in Die Walküre. Choreography by Tinovimbanashe Sibanda enacts some of these events.

Act II brings us Ryan Speedo Green’s Wotan, Tamara Wilson’s Brünnhilde, and Saturnino’s Fricka. Saturnino was a Santa Fe apprentice singer in 2021 and 2022, and she’s a real find. She has a big, smooth mezzo and a regal presence, singing lyrically and with force. Likewise, Green is both vocally and dramatically impressive as Wotan, dominating the stage and singing with firm splendor. This was his role debut, and while there’s always room for growth with such a complex character, he’s well on his way to being a major interpreter.

Curtis Brown

Like Miknevičiūtė, Wilson has a bright voice, with plenty of richness in her middle and lower registers. As directed here, she’s more musically expressive than physically, moving majestically through the opera. Of course, much of the first half of Act II is conversational, between Fricka and Wotan, then between Wotan and Brünnhilde.

The second half, though, is full of action, with Siegmund and Sieglinde fleeing Hunding, Sieglinde’s desperation, and finally both Brünnhilde and Wotan intervening in the final confrontation between Siegmund and Sieglinde. Still stages all of this vividly, with vast scenic elements moving around the stage. She places Sieglinde inside a gold-lined object while young Sieglinde looks on. But why does Wotan dispatch Siegmund, stabbing him with a knife? Is this his special way of making up to Fricka?

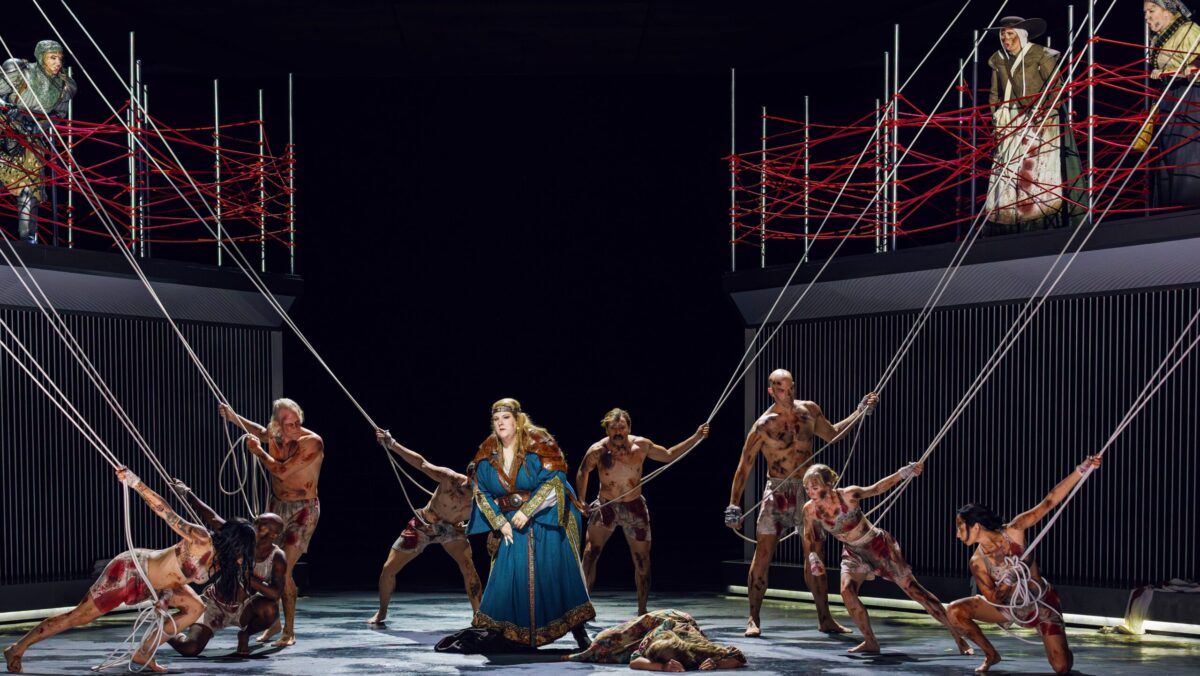

Act III opens with perhaps the best-known Wagner bleeding chunk, the Ride of the Valkyries, a challenge for any opera house to stage convincingly. The Crosby Theater is not equipped to fly either scenery or people, and Still, perhaps working with Sibanda, has come up with a fine solution to the problem: the Valkyries stand on the upper level of the set, while dancers on the stage, apparently representing both the dead heroes and the Valkyries’ horses, writhe and dance and leap about, clutching ropes or giant bungee cords attached to the roof of the theater.

Curtis Brown

The Valkyries, who include such stars as Jennifer Johnson Cano and Wendy Bryn Harmer as well as former and current apprentice singers, are costumed as warriors from different periods. Collectively, they made a mighty noise.

Still stages the closing scenes between Wotan and Brünnhilde tenderly, and Green and Wilson carry them off beautifully, though the director makes a surprising misstep: at the close of the opera, the score and libretto direct Wotan to strike Valkyrie rock three times with his spear, summoning Loge to set the magic fire around Brünnhilde, and Still inexplicably drops this small action, which makes more of a difference than you might think. Nonetheless, the staging of the magic fire is beautiful and moving, with Brünnhilde inside a vast, flaming cube as her father leaves the stage.

The singing and staging were so effective in this Walküre that it’s particularly disappointing that James Gaffigan’s conducting simply wasn’t on the same level. Particularly in Act I, he’s positively soporific and it’s not a matter of his tempi. While they were a tad slower than an average performance of Die Walküre, it’s possible to perform Wagner extremely slowly with no loss of momentum. Mark Elder’s five and three-quarter hour Meistersinger in San Francisco a decade ago was by far the slowest Wagner I’ve heard live, yet it was lively and absorbing throughout, with glorious orchestral sound.

Gaffigan was competent in keeping the orchestra and singers together, and in not overwhelming the singers, but where was his interpretation? Each Act felt like a succession of notes with little direction and with no overall shape or concept of structure. There was no drive up to big moments, no falling away. What a shame, with such an excellent cast, that the conducting wasn’t just as good.