Late at night, headphones on, covers drawn to my chin, I’d thrill to the voice as if it were my own. I was 10 years old. The opera was the1978 RCA recording of Verdi’s Otello, and the baritone – roaring over James Levine’s fortissimo conducting – transformed into a larger-than-life character, sweetly goading here, bluff and muscular there, obliterating and dominant still elsewhere.

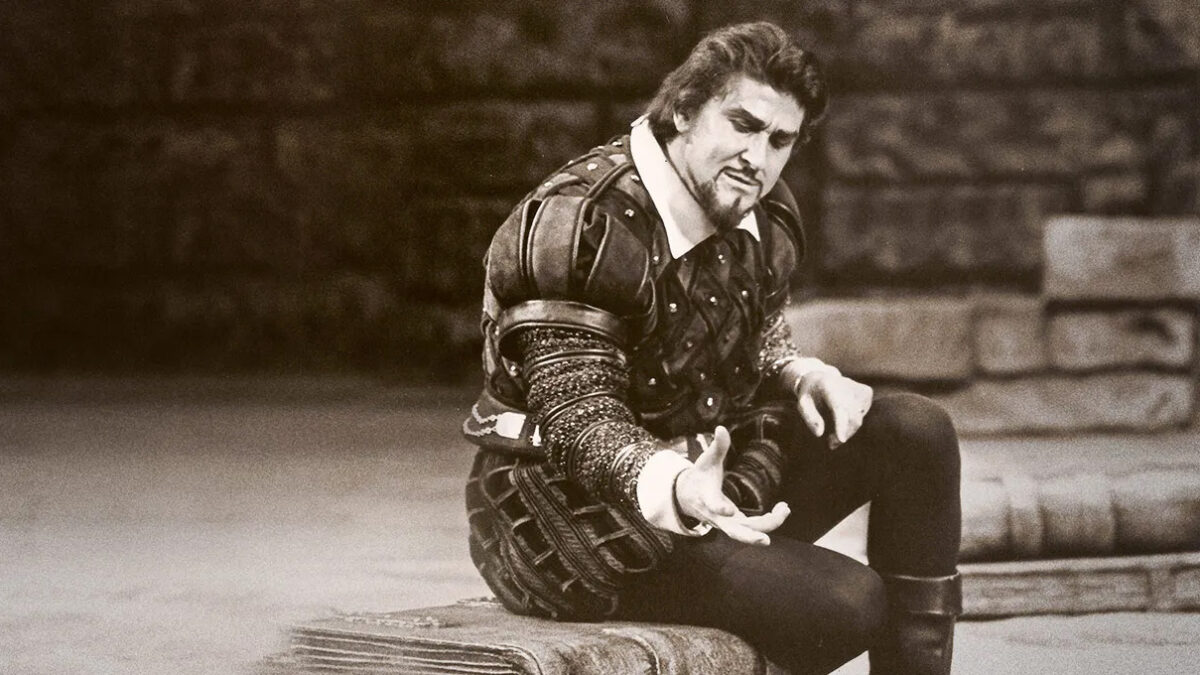

Then my dad showed me a production. This same baritone – with close-set eyes, long nose, mane of brown hair, and a neat beard sculpted thin and close to his jaw – prowled the stage with long legs and a barrel chest. He embodied Iago: coolly mendacious, strapping and feline. He launched into Iago’s Credo – “Credo in un dio crudel” / “I believe in a cruel God..” – and I watched him, eyes wide, stomach tight, as he bounded across the stage, spurred on by the stab of trumpets and slither of strings.

By the Credo’s end, both he and I were breathless. “E poi…? / “And then…?” He asks pensively. “E poi…?” A pause. The basses and cellos groaned in the murk; his face twisted into a rictus grin: “E morte è il nulla.” – death is nothingness. The orchestra exploded and the air shook with a final phrase – “è vecchia folla il Ciel!” / “Heaven is an old wives tale!” – and Iago, grabbing his head in psychotic agony, danced back into the darkness.

That baritone was Sherrill Milnes, and it’s not hyperbole to credit this performance with unlocking for me the worlds of theater, music, and later, literature. In short, Sherill Milnes changed my life.

In the opera world, Milnes is more than a man – he is a mythic figure in the same vein as some of the greatest voices in history: Vickers, Pavarotti, Sutherland, Scotto, Ghiaurov. In a career spanning three decades, he performed 652 times at the Metropolitan Opera (and, by his estimation, as many at home as abroad), taught master classes at Yale and Julliard, conducted major orchestras, sang for three presidents, and won three Grammys.

This year he celebrates three more achievements: his 90th birthday, the 60th anniversary of his debut at the Met, and the 25th year of VOICExperience, an organization he founded with his wife, Maria Zouves, which helps cultivate new generations of vocal talent in a range of capacities within the music industry.

I recently met with these important artists for an hour-long video interview where we discussed a range of issues – his teaching and mentorship, the vocal challenges he faced in the 1980s, even his favorite late-night snack. Yet there is one question that stands out, that frames the life of the man as if he were a subject in a Norman Rockwell painting: how did Sherrill Milnes go from milking cows on a farm in Depression-era Illinois to become the greatest Verdi baritone of his generation?

“When you are milking,” writes Sherrill Milnes in his autobiography, American Aria, “one of the most painful sensations you can feel is being hit right across the face by a sudden swish of a cow’s tail.” Growing up on a farm outside Chicago, Milnes would milk 20 cows twice a day and fork bales of hay with his family. As he began to learn opera, he’d stand atop his family’s red-orange Allis Chalmers tractor and throw back his head in Iago’s maniacal laughter, or Don Giovanni’s seductive chuckle.

When I spoke with him recently he appeared well-groomed and dignified, with swept-back silver hair and a manicured mustache and goatee. An animated talker, he emphasizes his points with firm wags of his head and plunging motions with his hands. “It was suburbia,” he said of his hometown Downers Grove, located about an hour west of Chicago by train. “I think my brother and I were maybe one of two farm boys in the school. It was not a farm community, per se, but it was a musical community.” Either way, Milnes was no silver spoon son. Once, after walking miles in the snow to a piano recital (a horse was not available), he felt a burning in his foot. When he arrived at the venue, he realized a nail had dug a hole into his toe, filling his boot with blood. He played anyway.

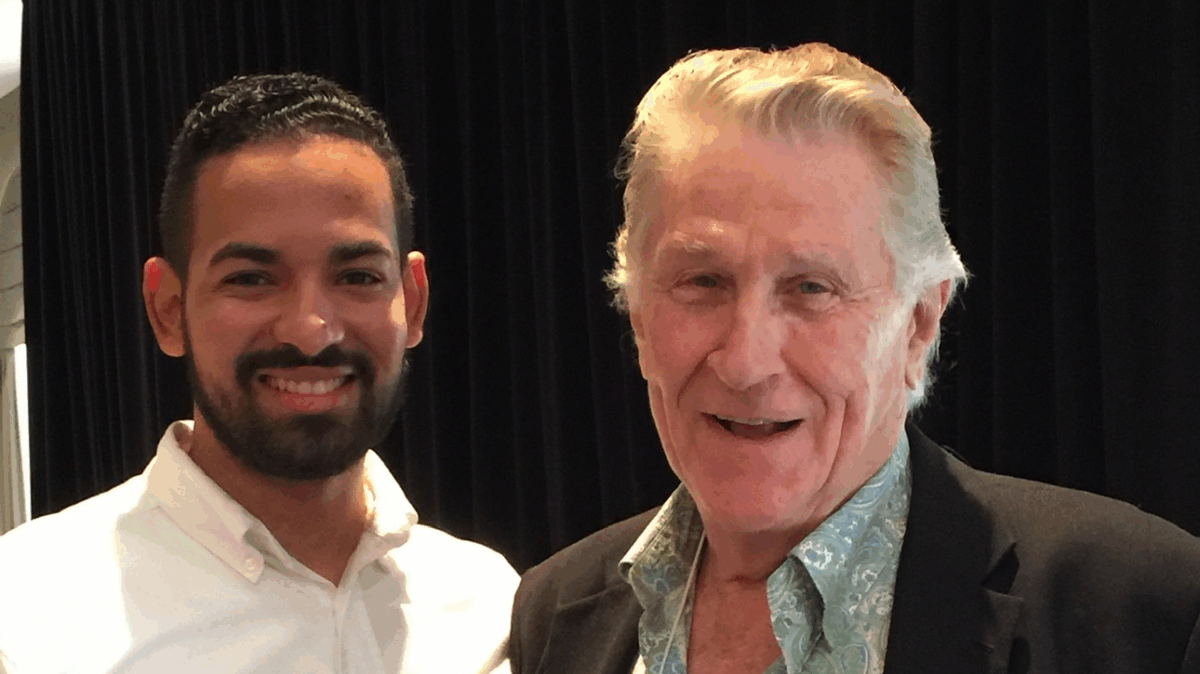

Milnes and his wife, soprano Maria Zouves — Photo courtesy of Sherrill Milnes

Milnes credits his mother, a singer, pianist, and choral director, for teaching him music. At first, this meant a range of instruments, all of which he mastered, including the tuba. He worked hard refining his voice, studying at Drake and Northwestern Universities and singing in the Chicago Symphony Chorus under the legendary Margaret Hillis. His big break came with the Goldovsky company, after which he tried out for the Met. The rest is history.

Many have tried to describe Sherrill Milnes’s voice in its prime; a few have come close. “He has had one of the most beautiful, God-given voices,” Placido Domingo once said, “The timbre is superb; the easiness, the legato — absolutely beautiful.” In a 1979 article in the New York Times – headlined “VERDI WOULD HAVE LOVED HIM” – Tony Randall, of Odd Couple fame, described his voice as “extremely bright and strong…tangy and warm.” The LA Times called it “darkly shining.”

Vocal versatility was far from his only skill. Milnes was the rare five-tool baritone. In baseball, a five-tool player is one who can hit for average, hit for power, run fast, field their position, and throw bullets, strong and accurate, all over the diamond. Such was Milnes. “Sherrill had everything. He was a fantastic musician, he was sexy…there wasn’t a high note that didn’t work, and he was a great collaborator…He was a great linguist; you believed him when he was singing the language,” says Maria, a Greek-American soprano with bubbly charm. (At this, Milnes, with characteristic good humor, looks around in mock-innocence, “Hey, who are we talking about?”)

All of this – the looks, the voice, the dramatic presence – made Milnes the most popular baritone in the world. He was invited to the Ford, Carter, and Reagan White Houses to perform; he boasted friendships with Tony Randall, Gregory Peck, and Burt Lancaster. Milnes recorded some of the most iconic performances in opera history: the 1972 Lucia di Lammermoor on DECCA with Pavarotti, Sutherland, and Ghiaurov, and the aforementioned Otello are two personal favorites and widely considered benchmarks.

Much has been made of Milnes’s place in the Tibbett-Thomas-Merrill-Warren lineage of great American baritones. Milnes had a steely ring that none of those great men had. Warren had a darker voice with excellent top notes, but, to me, is often froggy; his “Credo” is muddled and stiff compared to the spine-tingling, rafter-shaking Milnes’s. Merrill perhaps matched Milnes as a “singing actor,” but lacked punch. Listen to Merrill’s “La pietade in suo favore” from Lucia, for example – plodding and colorless compared to Milnes. And no one can match prime Milnes in the “Si pel ciel” at the end of Act II of Otello, as he jumps up to a high A instead of the written C sharp.

The clarion As and B-flats that continue to make the heart leap with surprise are a trademark of his oeuvre and gave him tremendous physical pleasure – second only to sex, per that Times interview. Yet they were far from effortless. As he writes in his memoir, “I’ve never been what I call in the industry an ‘easy’ singer. It takes a lot of energy to get my tone going. Some fine singers…don’t appear to use a lot of effort to sing, their voices seem to flow like water out of a tap…I always have had to put a lot of juice into my singing.”

Perhaps it was this wrenching effort, perhaps it was over-use. (He once sang in Eugene Onegin, Otello, and La Favorita on three consecutive nights.) Perhaps it was the demands put on baritones by Verdi himself; many of his works require an unusually high tessitura – a sort of range within a singer’s given range. “Especially in Verdi,” Milnes said to the opera critic Bruce Duffie in 1985, “it seems like every time the baritone opens his mouth, the brass are trying to get you. Certainly there’s a lot of fat, rich playing from the orchestra over which one has to kick the voice.”

Whatever the reason, hubris or happenstance, the burnished, brassy voice, decorated with applause the world over, would soon begin to fail.

In the early part of the 19th century, the French soprano Cornélie Falcon was cruising through the now-obscure grand opera Stradella when her voice suddenly collapsed. Hector Berlioz, who was present, writes of “raucous sounds like those of a child with croup, guttural, whistling notes that quickly faded like those of a flute filled with water.” Falcon fainted. For months she hoped to nurse her voice back to its former supple richness. To no avail. Her career was over at the age of 23.

Such scenarios haunt the imaginations of all singers.Though often brought on by overuse or poor technique, vocal cord injuries can happen for a variety of reasons — “It was that simple. I sneezed and I hemorrhaged,” Denyce Graves once recalled – but when your body is your instrument, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Photo courtesy of Sherrill Milnes

In the spring of 1981, Sherrill Milnes was preparing for the role of Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet. The three-hour dress rehearsal was scheduled for the same day as the performance. “This schedule has always killed me in terms of my vocal and physical energy,” he wrote in American Aria. This time, however, it was unavoidable. In addition, the opera was, and remains, relatively unknown, so the orchestra was sight-reading, a situation which Milnes felt he could help by “slugging,” or laying on the voice…giving too much emphasis on the beats, to help the orchestra and the conductor feel and set tempos.”

Towards the end of the performance, Milnes felt an “odd, breathy sensation.” The next day, he couldn’t talk. His voice started to crack, like an adolescent boy. As the condition persisted, he began to cancel performances. Doctors put him on a “sing-rest” regimen. It didn’t work. Lying in bed at night, drenched in sweat from anxiety, Milnes feared the worst. “When a singer can’t sing, it can destroy you,” he writes. “You feel weak, stripped of your strength, impotent…” Doctors diagnosed him with a burst capillary in the vocal cords, for which he twice underwent laser surgery, a treatment then considered cutting edge but later revealed as detrimental for the way the heat inflames surrounding tissue.

Milnes continued to sing at a high level for another two decades, though with diminished endurance and vocal strength. The top notes didn’t come as easily. And while he continued to bring down the house in his various signature roles – one Otello in Vienna in 1991 received an hour and 45 minutes of applause and 101 curtain calls – many listeners note a wobble or huskiness in the later recordings. Milnes himself writes that he could only sing for about an hour before the effort began to affect its quality.

Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Opera Archives

Eventually, the Met, after 30 years of employment, informed him – by fax – that there was no room for him on their roster, vaguely citing “performance problems.” In his memoir, Milnes recounts this event with some bitterness, but also realism. “During those last two years [at the Met], I suppose I should have seen the handwriting on the wall. In the business world, when one starts being honored, that generally means you’re being retired.”

It is difficult to imagine that Milnes – supremely confident, if not arrogant, in interviews during the 1970s – feels no disappointment about the injury that limited his career. In our conversation, he framed the experience again in terms of an aging athlete. “A lot of people think that singers stop singing because we’re tired of it. Not true. You know, a quarterback at 39 or 40 years of age – the muscles change, they get weaker. There are things you can’t do.” Maria and Sherrill credit Milnes’s self awareness of the situation for the longevity of his post-injury career, picking and choosing roles that were right for his voice, citing Falstaff as an example.

Usually, singers call it quits around 65 or 70. Milnes was just 46 when he suffered his vocal injuries. Milnes, however, would continue to teach and mentor, launching in 2000 the VOICExperience project that would cement his legacy.

Milnes sometimes jokes that he took off teaching for 42 years to sing around the world, and now he’s back to what he’s meant to do. When I asked him what he loves about teaching, he responded with one word: “Results. Hearing somebody improve, seeing them improve. Even if it’s just in the eyes, the face. Very important. I wouldn’t say more important than the voice, but certainly as important.”

In an interview at the National Opera Center in 2015, Milnes gives a glimpse of how he approaches teaching sessions. “I listen to someone sing and I think, ‘what can I give them that will make them better now?’ Sometimes it’s language, sometimes it’s involvement,” he said, referring to nonverbal cues. “Doing something [with your body] is always better than doing nothing.” Milnes focuses on a range of characteristics, not just the voice. “Some people will sing a high note,” he said in the NOC interview, mimicking rapid blinking. The audience laughs. “Well, that’s very disconcerting!”

VOICExperience started as a series of masterclasses by Sherrill Milnes as a guest of Disney entertainment in Florida and this continued for 13 years with the guiding principle of “inspire within reality,” a mantra that encourages young singers to be realistic about the kind of impact you can make in opera. Not everyone can be a superstar. So what then? “You can be a community choral director and be just as meaningful in the world as a Sherrill Milnes,” Maria said. This practical outlook is at the core of the VOICExperience programs, the efficacy of which can be found on the Festival’s “Where Are They Now?” page.

One grateful student is Jean Carlos “JC” Rodríguez, a 35-year-old Dominican baritone who happened to meet a Milnes acquaintance while working for Opera Tampa. After he impressed her with his singing, she referred him directly to Milnes, who invited him to audition at his home. “What I’ve learned is how to interpret music in a way that feels organic. [He’s] a believer that you should be playing, singing a character as if you don’t know what you’re going to say next.” In what is perhaps a lesson learned the hard way, JC also said that Milnes taught him to pace himself, saving voice in reserve for the moments that really matter.

Photo courtesy of JC Rodriguez

The Savannah Voice Festival, started in 2013 as an outgrowth of the VOICExperience, was designed not only to showcase the tutelage and mentorship of the VOICExperience, but to make opera, musical theater, and song more accessible. “Part of our mission is offering opera in a smaller setting…how do we bring it into every community? How do we allow kids in school to be exposed to it and demystify it?”

At the Festival, Sherrill and Maria work to pare back operas for a family-friendly experience. “Audiences now require shorter concerts,” Milnes said. “That’s the truth. We like to do cuts. We don’t cut out any of the meat. We cut out some of the fat and bring it down to an hour and a half, two hours. [People] love that.” It is their 13th year doing the Festival, which will take place from August 7th to the 17th in Savannah. For Maria, the Festival manages the double feat of both engendering community and showcasing “the magic of the human instrument working at Olympic capacity to tell stories.” The couple wants VOICExperience to continue long after they are gone.

After such an illustrious career, one could understand if a singer and teacher of Sherrill Milnes’s caliber took a back seat to proceedings, perhaps attending some events between tee times. Not so with Milnes. Rather, he spends his days working and teaching. “When we get him to the festival, he sits in those classrooms and he teaches longer and harder than anybody else,” Maria said. Perhaps this is no surprise at all for a onetime farmboy, who has demanded excellence from himself and others throughout his life and career.

Photo courtesy of Sherrill Milnes

It’s easy to think of Sherrill Milnes and Maria Zouves as monuments – they are, but they’re people, too. Maria enjoys Marvel movies. Sherrill’s favorite late-night snack? “Popcorn with butter. A lot of it. I want no popcorn or a lot of popcorn. It’s like ice cream. I want no ice cream or a lot of ice cream.” Asked what moment they’d choose to relive in their personal or professional career, each answered poignantly. Milnes chose their wedding; Maria cited the birth of their son.

Milnes has featured on the soundtrack of my life from almost the beginning up to today. When I went to college, as my hometown receded into the distance, one of the tracks I had on repeat was Domingo and Milnes singing their fraternal duet in Don Carlos. The ravishing harmonies fill the soul with hope, determination, and brotherhood. In La traviata, as the imploring Father Germont, his phrasing is urbane, the legato flawless, weaving above and below the sweeping strings. His duet with Violetta in Act II has been on repeat for the last week, guiding me gratefully through spreadsheets and emails.

And I will keep on listening, thrilling to the voice as I did as a boy of 10, now with the added comfort that his legacy will pass on, not just through videos and recordings, but in the living, breathing, singing generations to come.