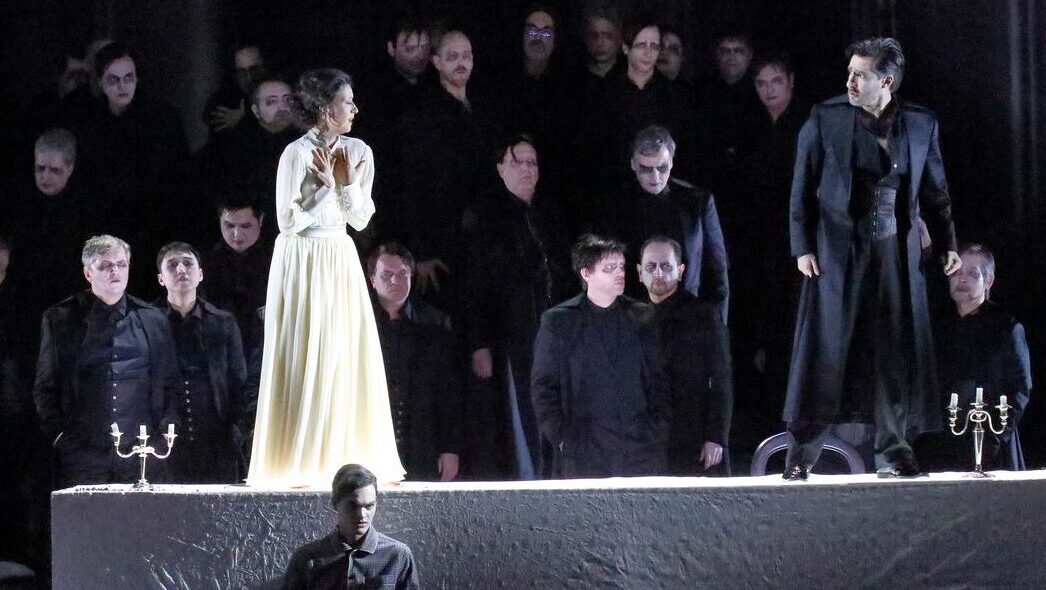

Wilfried Hösl (2022)

At the Bavarian State Opera, where German precision meets Italian passion in ways that would have amused the composer, Johannes Erath’s revival of I masnadieri (The Bandits) reminded a totally sold out Nationaltheater that some masterpieces can hide in plain sight. This combustible 1847 work burns with an intensity that makes you wonder why it ever left the repertoire. Then you get through watching it, and the answer crystallizes with uncomfortable clarity.

Written for London’s Her Majesty’s Theatre as Verdi’s first commission outside Italy, I masnadieri arrived at the tail end of what he later called his “galley years,” that brutal stretch of his career when artistic compromise wrestled with financial necessity. Friedrich Schiller’s German play Die Räuber (The Robbers) provided the source material, but Verdi and librettist Andrea Maffei performed radical surgery on the playwright’s social manifesto.

Out went Schiller’s sweeping indictment of corruption, in came an intimate family apocalypse that anticipates the psychological penetration of Verdi’s mature period. Carlo, the noble eldest son, transforms into a bandit chieftain after forged letters convince him his father has disowned him. Francesco, his scheming younger brother, orchestrates this deception while pursuing Carlo’s beloved Amalia and systematically driving their father Massimiliano toward madness and death.

Why this opera vanished from the stage becomes apparent within minutes of the opening. I masnadieri offers no quarter, no breathing room, no moments of conventional operatic comfort. Unlike Verdi’s later triumphs, which expertly balance intimate character studies with rousing choral spectacles, this work keeps piling one crushing solo showcase atop another until singers and audience alike feel battered into submission. The famous robber choruses provide brief respite, but they function as islands of communal energy in an ocean of relentless psychological excavation.

Yet when everything does align, with conductor, singers, orchestra operating at maximum intensity, I masnadieri reveals why Verdi kept fragments of its musical DNA alive in his later masterworks. Those robber choruses pulse with electricity that would later illuminate the conspirators in Rigoletto. Carlo’s anguished arias contain emotional chromosomes that would evolve into Manrico’s desperate nobility in Il trovatore. Most tellingly, the opera’s laser focus on sibling rivalry and patriarchal manipulation maps the psychological terrain that Verdi would mine throughout his middle period.

Under conductor Antonino Fogliani’s incisive leadership, the Bayerisches Staatsorchester deftly located this work’s restless spirit and sustained it without pause. Fogliani has carved out expertise in overlooked Italian repertoire, and his understanding of Verdi’s early aesthetic proved invaluable. He shaped the score’s episodic structure into something approaching architectural logic, emphasizing the melodic threads that connect seemingly unrelated scenes. When the music demanded ferocity, the orchestra delivered controlled violence that made your pulse quicken. In lyrical passages, they produced sounds of such ravishing beauty that you momentarily forgot you were hearing a “lesser” Verdi.

The Bayerisches Staatsorchester ranks among the world’s finest operatic orchestras, and their commitment even to Verdi’s problematic offspring demonstrates why Munich’s reputation extends far beyond Germany. The string section’s attack in Francesco’s manipulative scenes cut like surgical steel, while the brass section’s pronouncements during the robber episodes suggested both medieval pageantry and modern psychological warfare. You could hear why Verdi would later trust these same instrumental combinations to carry the weight of his greatest tragedies.

Wilfried Hösl (2022)

Equally impressive was the Bayerischer Staatsopernchor’s contribution under chorusmaster Christoph Heil. Those notorious robber choruses that punctuate the score require more than technical precision; they demand complete theatrical conviction from singers portraying men who’ve abandoned civilized society. This chorus delivered both with frightening authenticity. During “Le rube, gli stupri, gl’incendi, le morti,” the robbers’ celebration of pillage, rape, arson, and murder, the chorus sang with such committed gusto that the moral implications became genuinely unsettling. This wasn’t academic music making; it was theatrical transformation that reminded you why Verdi’s early works scandalized respectable society.

At the production’s molten center, Lisette Oropesa’s Amalia provided both the evening’s most luminous moments and its emotional anchor. The role, originally crafted for Jenny Lind, presents a gauntlet of coloratura obstacles that could easily devolve into vocal Olympics. Oropesa transformed these technical challenges into windows of character revelation. Her voice combines surgical precision with spontaneous emotional combustion, allowing her to navigate Verdi’s treacherous vocal terrain while maintaining complete dramatic credibility.

Her finest moment arrived when Amalia discovers Carlo’s survival. Oropesa executed a psychological transformation that bordered on genuine madness — not the decorative operatic variety, but something genuinely unhinged that made you question the character’s grasp on reality. Her voice, creamy and fluid, suddenly acquired an almost supernatural fragility that suggested a mind fracturing under impossible pressure. It was the kind of interpretive leap that separates merely excellent singers from true artists.

Wilfried Hösl (2022)

Charles Castronovo faced the Herculean challenge of humanizing Carlo despite the protagonist’s increasingly monstrous choices. This role demands both heroic vocal weight and sufficient psychological sophistication to justify a character who commands murderous thieves while claiming moral authority. Castronovo’s darker, more shadowed vocal timbre served the character brilliantly, an inner corruption taking over his noble soul. In Carlo’s Act II aria “Nell’argilla maledetta,” Castronovo traced the character’s descent from Romantic idealism to bitter disillusionment with such specificity that you could pinpoint the moment his soul cracked.

As the villainous Francesco, Alfredo Daza brought genuinely frightening kind of vocal authority, his warm baritone making his character’s calculated cruelty even more disturbing. Yet Daza’s most compelling choice was allowing vulnerability to flicker beneath Francesco’s scheming exterior. During his Act III confrontation with the dying Massimiliano, brief moments of filial grief enriched what could have remained cartoon villainy.

Erwin Schrott’s Massimiliano anchored the production with a gravitas that suggested both patriarchal dignity and tragic blindness. His portrayal of the father’s gradual recognition of Francesco’s true nature provided the evening’s most heartbreaking moments, particularly in the Act IV father-and-son duet where love and horror collide with devastating effect.

Wilfried Hösl (2022)

Erath’s staging approached I masnadieri as a chamber drama scaled to operatic proportions, serving the work’s psychological focus while acknowledging its structural peculiarities. Stage pictures appeared stark with monochrome backdrops, black walls, grayscale floors that emphasized mood and tension rather than realism. His visual palette emphasized shadows and harsh lighting contrasts that suggested both Gothic romance and modern psychological thriller. While a few directorial choices proved questionable, these remained quibbles rather than major failings that might have undermined the production’s overall achievement.

Experiencing I masnadieri in live performance confirms its significance in Verdi’s artistic evolution. This is where the composer discovered how psychological authenticity could transform operatic convention, how individual character could reshape dramatic structure. You can hear La traviata’s death scene gestating in Amalia’s final stage moments. Rigoletto’s father-and-daughter dynamic emerges from Massimiliano’s relationship with his sons. Most significantly, the opera’s exploration of how noble intentions may curdle into destructive obsession would later reach full flower in Il trovatore’s Manrico and Un ballo in maschera’s Riccardo.

Lengthy applause at the end confirms that the Staatsoper’s revival a particularly strong case that this volatile, demanding work deserves rescue from its current neglect. This was a near-perfect production of a near masterpiece which had my cohort of opera fanatics reaching for superlatives.

Not every masterpiece arrives fully formed. Sometimes the most revealing artworks are those that show us genius in the act of becoming itself; I masnadieri offers exactly that kind of revelation, provided you’re willing to listen to the sound of a great composer learning how to be great.